Pig Village and the mockery of Cymraeg

Stephen Rule (Doctor Cymraeg)

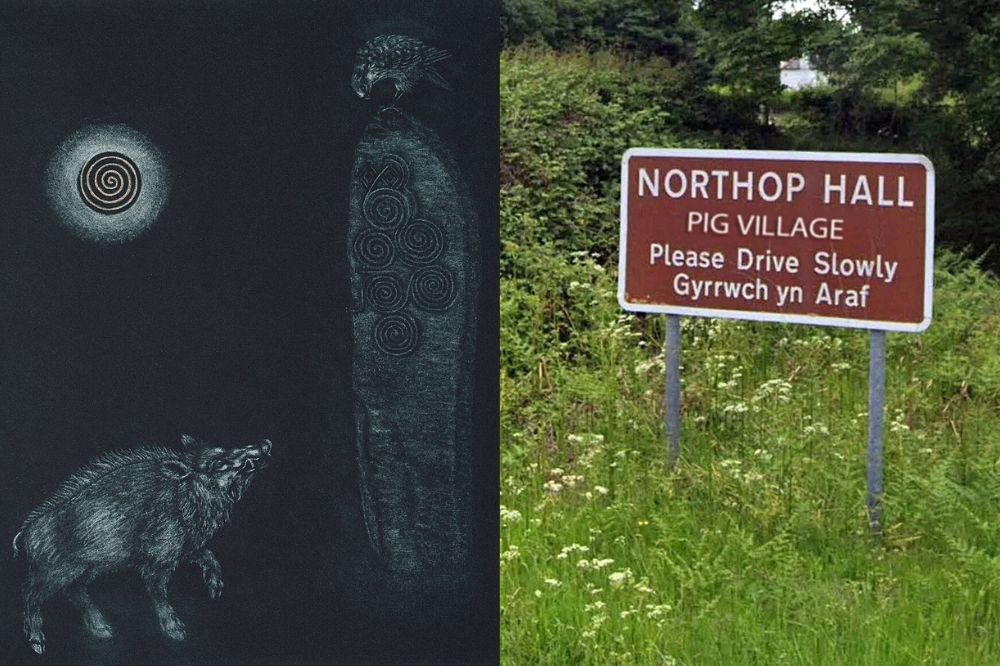

A few months back, Northop Hall found itself in the news. Not for a scandal, or a bypass proposal, or a council funding row… but for pigs. Or more specifically, the threat of pigs on a sign.

The local council had suggested including Pentre’ Moch (the Welsh name) on signage alongside “Northop Hall.”

You’d have thought they’d proposed a sewage plant!

Articles appeared in print, on TV, and online… some balanced, some bemused, but most lacking even the faintest curiosity about what the name meant or why it mattered.

And that’s what gets me. Because Pentre’ Moch is a beautiful name. Not crude. Not silly. Not offensive.

Just old. Local. Rich in story. Rooted in a Welsh cultural landscape that rarely gets to speak.

Anglo-centric media landscape

But this is what happens in a country where print and television media remain overwhelmingly anglo-centric. We live in a land where you can grow up knowing the names of Manchester United’s back four better than the history of your own village.

Where Welsh is treated as quaint, exotic, or, God forbid, embarrassing. And where even the most mythic, storied parts of our toponymy are flattened into punchlines.

In the vacuum created by English-dominated media, Wales is often left without the tools to explain itself to itself.

Which is one of the many reasons, I believe, why Wales voted with England in the Brexit vote.

We didn’t see ourselves as distinct – because we’re rarely given the chance.

So why pigs? Why Pentre’ Moch?

Well, for one thing, Wales is absolutely littered with pig-place-names. Mochdre. Mochnant. Mochras. Llarhaeadr-ym-mochnant.

You can barely go more than twenty miles without bumping into a herd of them on the map… or whatever the collective name for a group of pigs is!

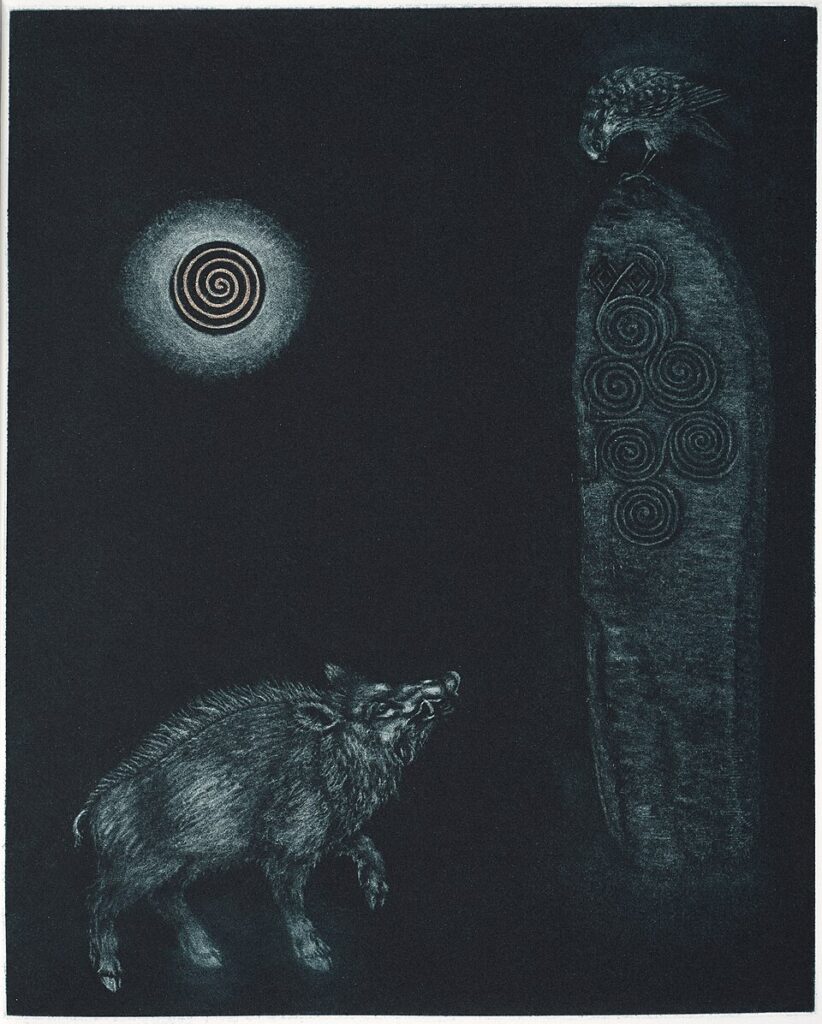

And these aren’t random. They’re not culinary tributes or farmyard jokes. These names speak to something deeper; the symbolic power of pigs and boars in Celtic mythology.

From the monstrous Twrch Trwyth of the Mabinogi, hunted by Arthur himself, to the sacred pigs of Irish and Welsh legend that could lead you to the Otherworld, these animals were more than meat.

They were messengers. Warnings. Treasure-bearers. Transformative forces. In short: they mattered.

And they still do… or, at least, they should. Because the fact that the name Pentre’ Moch could make headlines in the first place says everything about the cultural ecosystem we live in.

An ecosystem shaped by anglo-centric media; one often too arrogant to ask, or too ignorant to care.

Imagine if one of those articles had paused long enough to wonder: Hang on, why would a village be named after pigs?

They might have uncovered a web of stories that stretched back over a thousand years.

But curiosity doesn’t sell. Mockery does.

For more from Doctor Cymraeg, follow on X and Instagram.

Doctor Cymraeg’s handy books for learners can be purchased from Amazon, or directly from Doctor Cymraeg’s Instagram account.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

The loss of traditional names is terrible. Near Tatton in Cheshire is Dirty Lane which a load of rich incomers from Manchester have had renamed Cherry Tree Lane. Dirty obviously meant muddy or wet I suspect like Heol Bwdl in Pencae near Llanarth in Ceredigion.

What about Wtra Domlyd (manure alley) in Dolgellau? People in that town respect their old names. Pity Northophall people haven’t the same nouse – especially as the name in English sounds like a tablet for erectrile dysfunction!!!

Are you accusing English Premier League footballers of being uncultured?

‘Near Tatton in Cheshire is Dirty Lane which a load of rich incomers from Manchester have had renamed Cherry Tree Lane.’ It’s a very quiet by-road in the civil parish of Rostherne, and runs west to east just south of the river Bollin. I grew up only a few miles from there, and clearly remember the change to which you refer happening. In fairness to those who lobbied to bring it about, it was done in the aftermath of the prosecution of a couple of blokes convicted of ‘indecent behaviour’ in a car parked on the side of the road,… Read more »

Ignorance is endemic. I once had to explain the etymology of Caerdydd…to people who were born and bred in Cardiff. A lack of knowledge and understanding often manifests itself in a condition of self-loathing (which is when you read the Daily Mail and vote Reform).

A’n gwaredo people who live in Mochdre!

In English Pig Town, or Swine Town, is known as Swindon.

This sign on the M4 is offensive.

Should be renamed Expensive Petrol.

From the monstrous Twrch Trwyth of the Mabinogi, hunted by Arthur himself There is NO Twrch Trwyth and NO Arthur in the Mabinogi. Both appear in Culhwch ac Olwen which is a tale in The Mabinogion, a book of 11 tales. To grasp the difference and remember it, one title is longer than the other. MABINOGION contains MABINOGI. Just so the Mabinogion book of eleven tales contains the Mabinogi saga. It would also be appropriate to mention that there are many pig references in the Mabinogi itself. A new breed of pigs are a gift from mighty Annwfn to the… Read more »

Hi Shan,

I have heard a story about a gold pig in the Northop/Northop Hall area being recorded in a book in Ruthin library?!! I’m curious if anyone has heard anything about this story?

Agree with you entirely Stephen. Just as an aside I remember this saying from years ago from a farming gathering.

Your dog will always look up to you.

Your cat will look down on you with disdain.

Your pig will look you in the eye as an equal.

“mochnant” (with a short “o”) signifies a rapid stream – nothing to do with pigs.

Da iawn, cytuno chwilfrydedd sydd angen yn ein cyfryngau nid bod yn goeglyd nag chwaith yn grachaddysgiedig!

Whether or not places named after pigs is due to mythology or farming, it’s an interesting point about understanding place names. England is similarly littered with pig-inspired place names, and people won’t understand their meaning. Swincombe in Dartmoor is perhaps a mix of Old English for pig and Brythonic for valley, showing the lost Brythonic culture of areas now long lost unfortunately.