Postcard from Shrewsbury Prison

Sarah Morgan Jones

With a layover just short of two hours in the town of Shrewsbury, I decided to relax and spend some of that time in prison. Never having set foot in one before, I thought it would be an educational and weirdly wholesome way to wait for my connecting train…

The decommissioned prison is currently the star of the weird reality TV show Banged Up in which ‘celebrities’ – Neil Parish, Johnny Mercer and Peter Hitchens among them – are locked up with real life convicts who are instructed to give their cellmates a taste of what prison life is really like.

As a good and typical example of a Victorian prison, the views from the landing are familiar from films and TV dramas, and indeed it has been the location for several, including Time starring Sean bean and Stephen Graham, Vicky McClure’s Without Sin, Man like Mobeen, the season finale of Happy Valley, and the remake of the Ipcress File.

The original building was built in 1793 by Thomas Telford, and prison reformer John Hiram Haycock and the present building was built in 1877. The site was decommissioned in 2013 having reached notorious levels of overcrowding.

Once plans for extensive student accommodation were rejected it was turned into a tourist attraction, replete with escape rooms, overnight stays, dinner options, ghost walks, axe throwing, guided and self guided tours. Hmm.

As I only had a short time, I didn’t argue when the impudent young man at reception floated the potential of an over 60 discount and grabbing the map, I made straight for the execution wing which houses the executioner’s bedroom, Albert Pierrepoint’s personal Airbnb just a few paces away from the room to which he took his condemned men.

Painted in institutional green, with a plain wooden cross above the iron framed bed and a wooden desk, the room certainly carried some atmosphere, although some curatorial bright spark has seen fit to add a black suited mannequin to the mix, which, bizarrely, was headless.

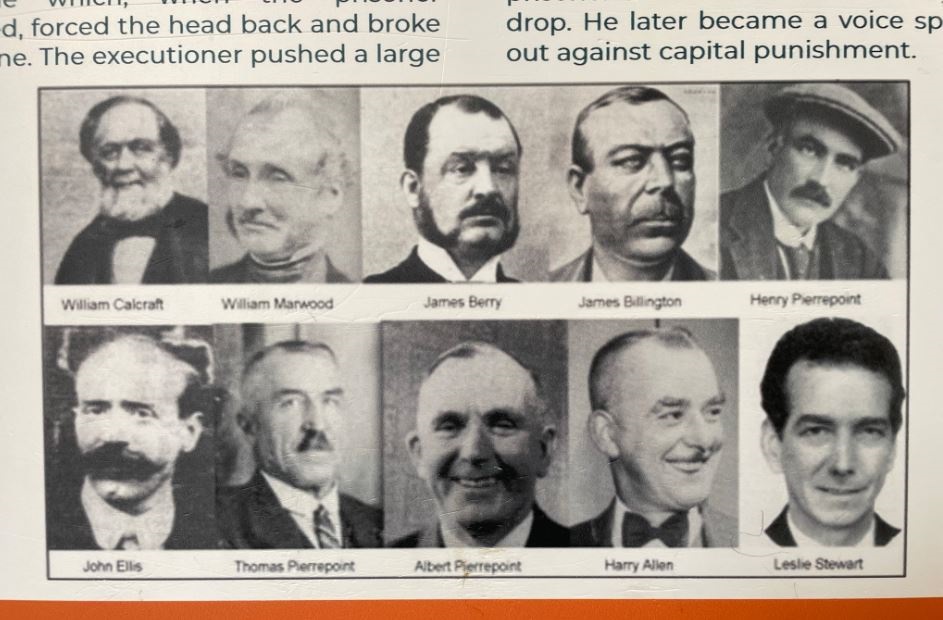

Before an execution, Pierrepoint, and his occupational predecessors would stay in this windowless room, ready to step into his role at 8 o’clock sharp the following morning.

Pierrepoint gained fame in his role for a number of reasons, including for his role in executing war criminals and high profile murderers such as John Christie and John Haigh.

He was also involved in contentious Welsh executions such as that of Ruth Ellis, who was born in Rhyl and was the last woman to be hanged in the UK. Her death was rumoured to have troubled him: rumours he flatly denied.

In 1950, Timothy Evans from Merthyr was wrongfully accused of murdering his wife and infant daughter, and hanged for the latter. The chief prosecution witness in his trial was the serial killer, John Christie, about whom the horrific truth only came out three years later.

In 1952, Pierrepoint hanged the wrongly convicted Mahmood Hussein Mattan in what was the last execution to happen in Cardiff. Mattan’s story is a catalogue of injustice and racism against which his family and supporters have been battling for decades, recounted in the award winning book The Fortune Men by Nadifa Mohamed.

Pierrepoint wanted to be an executioner, following his father and uncle into the trade, and approached his task with gravitas because the execution, he said, was “sacred to me”.

He believed his role was to dispatch the convicted man or woman as “humanely” as possible. Through calculation of weight and drop, using the long drop technique, he made fast work of his task, reducing the time from entering the condemned cell to the prisoner’s final moment to a maximum of 12 seconds and as few as seven seconds.

In Shrewsbury prison he hanged four men, all of whom were convicted for murdering women, including one Welshman, Harry Huxley, from Holt near Wrexham, who had shot and killed his girlfriend, Ada Royce.

Pierrepoint resigned in 1956 after a dispute over expenses incurred attending a scheduled hanging which was reprieved at the last minute.

Pierrepoint said after he retired: “I do not now believe that any one of the hundreds of executions I carried out has in any way acted as a deterrent against future murder. Capital punishment, in my view, achieved nothing except revenge.”

By the end of his career he had executed 433 men and 17 women. Add that total to his father’s and uncle’s and all in all, the Pierrepoints took the lives of 849 prisoners between them.

The last execution at Shrewsbury was carried out in 1961 by Harry Allen, Pierrepoint’s long-time assistant, who stepped into the grim shoes after Pierrepoint’s resignation.

Across the hall, the cell of the condemned man was right next to the execution room, which rigged up with a noose suspended form two brass hooks in the ceiling.

Disappointingly, though probably for sound health and safety reasons, the trap door and lever set up I imagine was originally there had been reconstructed as a boarded off hole in the floor, as if it were a shabby office awaiting the installation of a nice new spiral staircase.

Around the walls, boards told the story of the eight executions that had taken place within the prison walls between 1902 and 1961 – once part of a public spectacle, but later, mercifully, some element of privacy was afforded to the deplorable act.

It was very mundane in some ways, but not a place in which I wanted to linger.

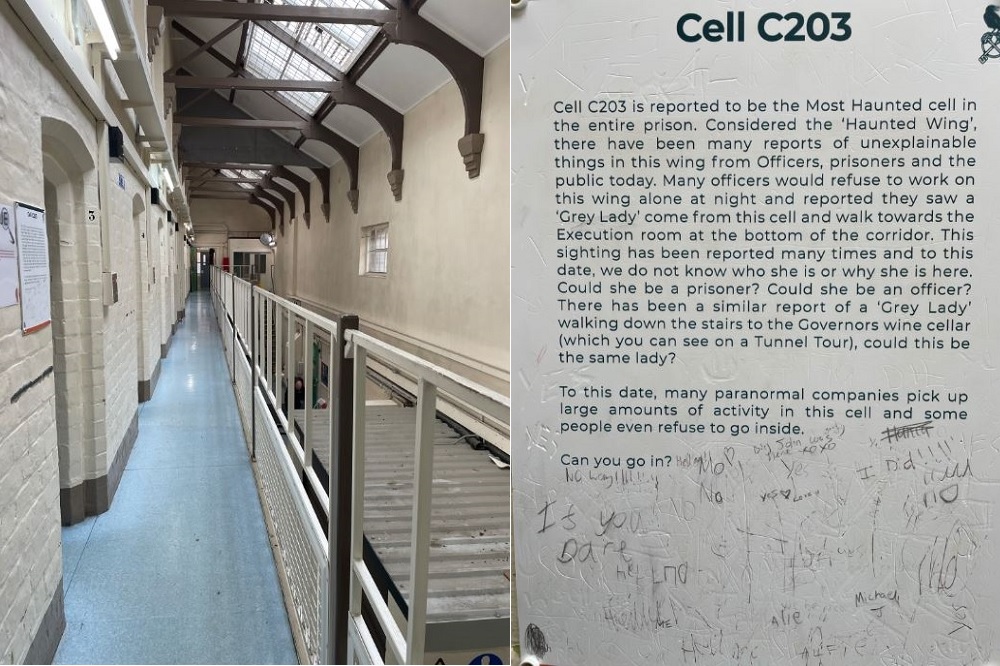

C Wing, apparently haunted to the rafters and the reputed home of the ghost called the Grey Lady, is a one-sided landing of tiny grim cells very close to the execution room. It housed up to 22 female prisoners before 1921 and then housed up to 43 vulnerable inmates at a time.

Reading the board outside cell C203, which claims that the room is the most haunted in the prison, I felt distinctly uncomfortable.

I normally don’t go for that kind of thing, but just as there are few atheists in the trenches, standing alone in a deserted wing which I was being told was haunted found me hedging my bets.

I hastened to the main A wing, which was originally designed to house 172 prisoners, but at the height of its overcrowding held over 400.

My unease grew stronger as voices of a distant tour reached me from the lower level, and to my great alarm, I heard someone running up behind me. Flattening myself against the painted brick walls, I turn in fright only to see no one there. The runner, I realised, was on the landing above me, so I styled out my terror and made for the stairs.

I can really see why people flashing torches and Ghost-o-meters around deserted farmhouses in the dark manage to freak each other out – this was just after 10am and broad daylight, and I could feel the panic rising in me, despite striving to channel my inner Del Hughes.

I scuttled down to where the tour was happening and overheard the guide getting properly into character as a warder (it sounded like he may have been one in a previous life), telling his tourists why restraint might be used, how many men would be needed to make sure it was secure…

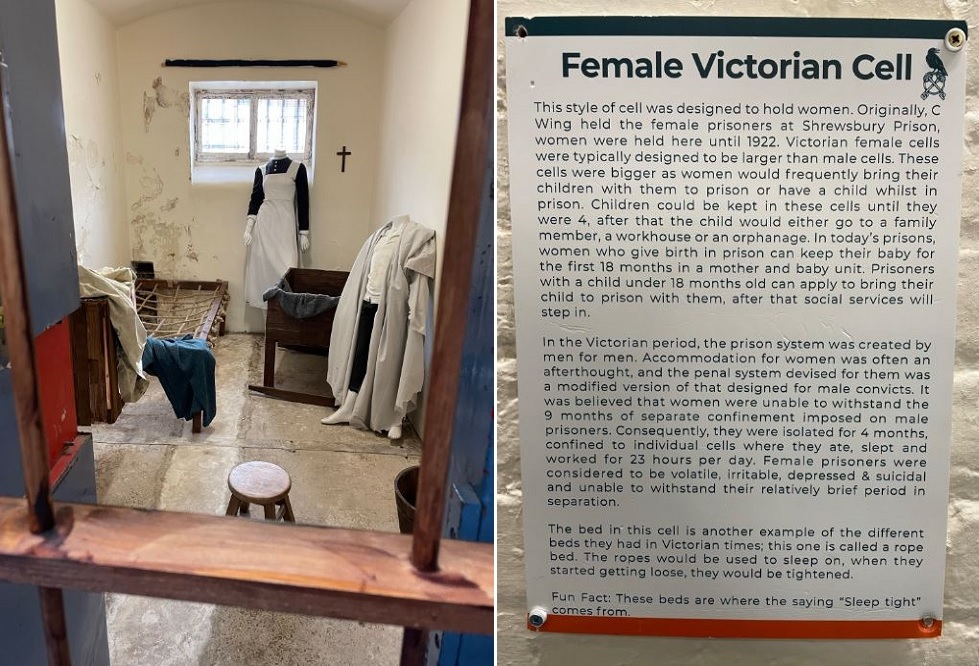

As he spoke, I peered through the doors of the exhibition cells – the Victorian female cell – women were incarcerated here until 1922 – the male cell, the constant watch cell, the padded cell…

I hadn’t seen the half of it, and I had time before my train, but that was pretty much it for me. The growing sense of panic and claustrophobia was overwhelming. I headed for the café, thinking a coffee might help, but I found I couldn’t speak to choose anything.

Seeing my discomfort, the assistant directed me out through the exercise yard, where I frantically searched for the exit, ran to the office to grab my bags and high-tailed it out of there.

The desperate celebs who want to spend time in this place get no sympathy for me, nor do the folks who part with good money to stay there for a sleepover. The threat of prison has always worked as a deterrent for me and continues to do so.

If I wasn’t over 60 when I arrived, I was on the way out. I had been there just 36 minutes. The fastest visitor ever.

Find out more about a visit to Shrewsbury Prison here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Well, it sounds dreadful, so you and I will deffo have to pay out good money for an overnight stay! Fab writing as always – and very evocative of the unease you felt whilst there. Maybe there really is something in this ghost business???