The astonishing Ladies of Llangollen lost portrait

Norena Shopland

There are three real-life portraits of the Ladies of Llangollen, world-famous for their same-sex relationship.

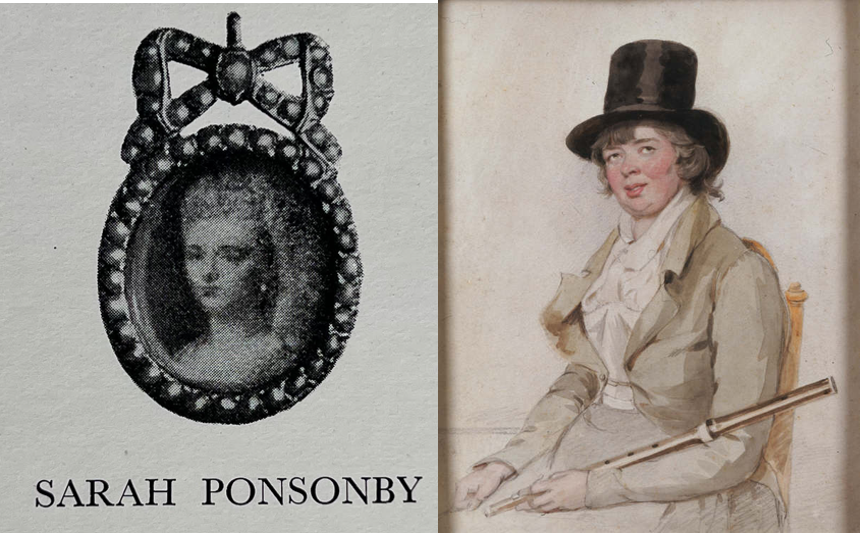

The first, a miniature c.1776 is of Sarah Ponsonby (now lost) and the second, ‘Lady in a Tall Hat,’ previously thought to be Lady Eleanor Butler, is now accepted as Sarah and is held in Plas Newydd, the Ladies home in Llangollen.

In both images, the high cheek bones show a similarity of features.

The third image is an illicit drawing of Eleanor and Sarah as old women, which was pirated to become their iconic portrayal in black riding habits that adorns many Ladies of Llangollen marketing materials.

However, there is a portrait of Eleanor which has been overlooked since it first came to light in 1914.

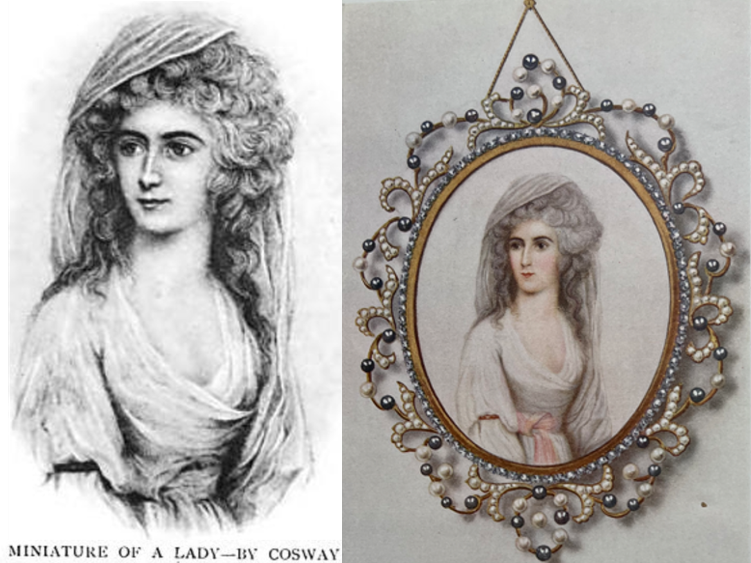

George Charles Williamson (1858–1942) was a leading art historian, who in The Studio magazine, discusses a miniature portrait. He was writing a book on Richard Cosway (1742–1821) an English portrait painter of the Georgian and Regency era, famous for his miniatures.

Williamson had heard ‘from various sources’ that one of Cosway’s ‘finest portraits’ called the ‘White Cosway,’ was in Ireland, and that it ‘differed in almost every respect from Cosway’s ordinary work,’ and was ‘one of the best things he ever painted.’

Williamson searched for the portrait and found it in the possession of Grace Butler, Eleanor’s great-niece. She told Williamson the portrait came about after Eleanor had been presented at the ‘Prince Regent’s court.’

This wording is significant, because when the heir to the throne Prince Frederick died in 1751, his son George became heir. Being a minor, his mother Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales became regent until his eighteenth birthday in 1756.

Augusta was a powerful figure who held her own courts and the fact the wording specifically says, ‘regent’s court,’ must mean hers, not the King’s.

There is no record of Eleanor having a formal court debut, simply that she was ‘presented’ at the Regent’s court. Meaning Eleanor could only have been there between 1751-1756 when she was between twelve and seventeen.

Born in 1739, she was around fourteen when she was sent to a French convent to be educated and she enjoyed her time there. Elizabeth Mavor’s biography claims Eleanor returned to Ireland in 1768 for her brother’s wedding, aged twenty-nine. But Mavor also suggests Eleanor remained in France for eight years, taking it to 1761 when she was twenty-two.

These dates are speculation by Mavor, and other biographers have not presented any other evidence.

Mavor’s reasoning for the long stay is that travel had been made difficult by the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). But, leaving a teenage girl in war-torn France, even in a convent, seems risky and it is perhaps more feasible that the family moved Eleanor to London before the war took grip. Putting her there in 1755/6 in time to be at the court.

Eleanor’s appearance apparently created quite a sensation by ‘her remarkable beauty,’ so her family asked Cosway to paint her. He made more than twenty sketches of ‘the girl’ before he could capture Eleanor’s beauty and unusually for him, painted directly onto plain white ivory, hence its name the ‘White Cosway.’

He stated it was the only way he could do ‘justice to the peculiar characteristics of her beauty.’

Grace Butler told Williamson that Eleanor took ‘a strong antipathy to Cosway’s portrait, and refused to have anything to do with it, because it ‘recalled what she was pleased to term the frivolous time of her life.’

Perhaps indicating Eleanor remained in London for some years. Cosway was only fourteen in 1756, it was not until 1762 that he became sought after, and there is no record he ever visited Ireland. Making it likely that Eleanor’s portrait dates to London sometime between 1762-1768.

Eleanor gave the miniature to her brother John Butler, 17th Earl of Ormonde (perhaps as a wedding present) and it passed to his wife Frances who gave it to their daughter-in-law Grace Butler, who in turn left it to her husband Lord James Wandesford Butler.

It was their daughter, also called Grace Butler that Williamson visited. On Lord James’ death, the White Cosway was sold in Ireland in 1898.

It was bought by Derby art collector William Bemrose (1831–1908), who included it in his 1898 privately printed catalogue where a black-and-white illustration referred to it as, ‘Miniature of a lady by Cosway.’ It was still in his possession when Williamson found it again and related its history to Bemrose.

After Bemrose died in 1908, it came into the possession of J. Pierpont Morgan the wealthy American financier, and Williamson was cataloguing his art collection. Did Williamson persuade Morgan to buy the White Cosway?

Morgan admired Eleanor’s portrait so much that he had a special frame made of black and white pearls so it could stand on his desk, and there it remained until his death in 1913.

Morgan’s son sold off all his father’s miniatures in 1935, and the current location of the White Cosway is unknown.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.