The curious case of the eisteddfod baton

Norena Shopland

With the National Eisteddfod nearly upon us (Rhondda Cynon Taff, 3-10 August) stories of past events and even scandals, are always an interesting backdrop.

One such scandal that ran for four years, was that of the golden baton.

It was made in 1888 as a competitive trophy for the National Eisteddfod but one of the most astonishing things about this baton is that it is gold – and not just any gold, but Welsh gold.

Controversy

Even before it was put into competition at the Wrexham National Eisteddfod it, and the man who had it made, William Pritchard Morgan (1844–1924), were causing controversy. It was intended for the lesser-known Welsh Choral Competition a decision which baffled some as it appeared to snub the more famous contests.

Anything to do with singing in the late Victorian period was followed avidly by the public and none more so than in Wales.

Choral singing dominated villages and towns, thousands of people were in choirs made up of hundreds of singers and locals were fanatical, following their favourites around the country.

Modern competitions such as X-Factor and Strictly pale in comparison, but the mania of the press was the same.

There were thousands of eisteddfodau across Wales, and competition for the prize money and trophies was intense with rivalry between north and south at its height.

Into this came the ‘Welsh Gold King’ with his golden baton.

National debt

Pritchard Morgan was an extraordinary man – he had been digging for gold on a mountain in the north and having hit a vein so rich was promising to pay off the British national debt. He was a fine singer himself and so loved the Eisteddfod he commissioned the golden baton.

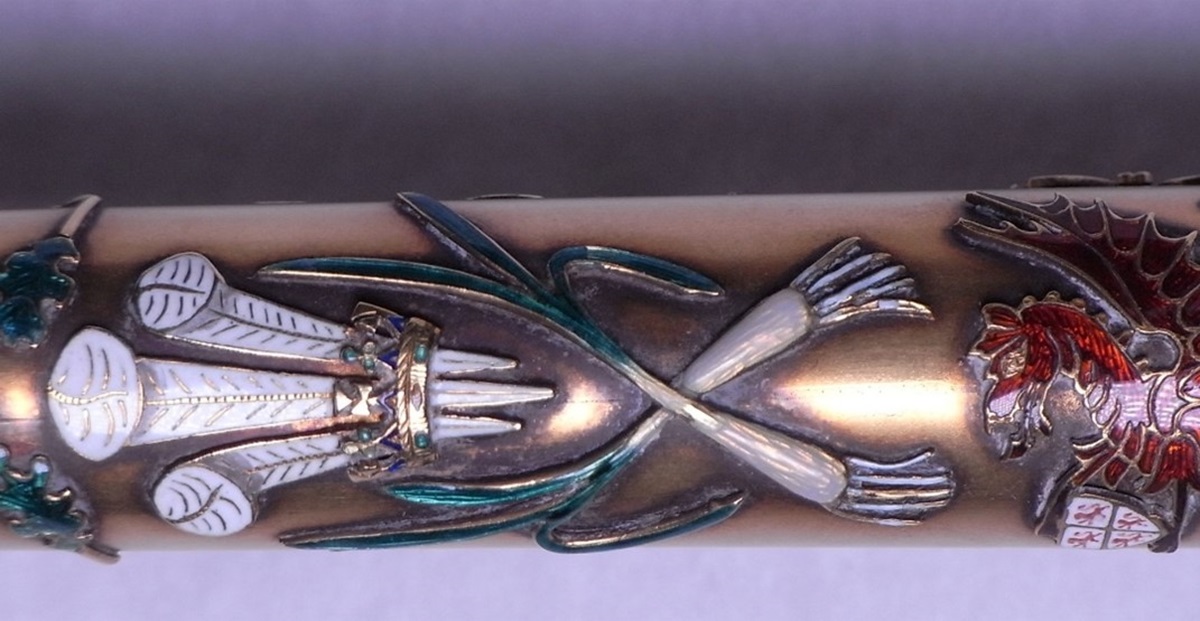

And it was like no other, emblazoned with Welsh symbols, a dragon, a druid playing a harp, leeks and studded with jewels, he would award it to the choir winning the Welsh Choral Competition two years running, to raise awareness and promote the native language.

But trouble and turmoil followed the baton as it was won back and forth from south to north Wales avidly followed by the media. Famous choirs took on the challenge to win it and every new development was reported, losers claimed there was cheating, disagreements were analysed, people took sides, bets were laid, critics censured, and the fame of the baton grew.

Finally, the Carnarvon Vocal Union managed to win it, but only just – for they had run out of money and the town had to dig deep to send them to the nationals. The win however was just the start of their troubles.

The conductor, claiming the traditional right of keeping challenge trophies (the choir would keep the prize money), refused to give up the baton and the choir tore itself apart taking sides until half of them sued their conductor for the return of the baton. It was a ground breaking case for they would change musical history – did a trophy belong to a choir or a conductor? Thousands came to hear the court’s decision but the judge decided, Solomon-like, that as none could agree it would be sold and the proceeds split.

Auction

At the auction the choir bid against the conductor to get their trophy back but a stranger at the back of the hall outbid them all.

He was acting on behalf of Swansea National Eisteddfod – or he thought he was – and when he returned home triumphant, the committee were deeply unhappy. Many, who wanted nothing to do with it, saw it as a poisoned chalice spreading disharmony and ill luck everywhere – and the final contest proved them right.

The baton was put into the Chief Choral Contest, where many said it should have been all along, and several famous choirs and conductors competed for it, including Carnarvon but all were beaten by the Llanelly Choral Society.

Riots

The win however was dogged with controversy and a losing conductor railed in the press of sectarianism, of adjudicators finding for locals to avoid riots, and the unfairness of it all.

Nevertheless, the baton had been won for the last time and it remained with Llanelly’s famous conductor, R. C. Jenkins. It did have a brief appearance in 1945 when the BBC interviewed surviving members of the choir in a review of Jenkins life and his influence on Welsh music, and they sang to the beat of the golden baton.

But the choir disbanded and the baton was handed down through family members until it was finally presented it to the Parc Howard Museum, where it sat wrongly attributed to a man who never won it and the true story forgotten.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Better keep quiet about it. If our cross border neighbours hear about the gold they will confiscate it and put in the British Museum. Oh, by the way, where is ‘Carnarvon’?

It’s a town somewhere between Amwythig and Yr Alban I think

You do realise that was the name of the choir at the time don’t you?

Yes, but it was completely wrong!! People still have difficulty getting it right. No one has difficulty spelling English placenames so why should we have a problem with Welsh ones? Always a case of “well, it’s close enough”.

Let’s hope it doesn’t meet the same fate as the Gold Cape of Mold.