The Exiled Radical – the poetry of RJ Derfel

Adam Pearce, Editor, Llyfrau Melin Bapur

It’s an interesting fact of the history of Welsh literature that the Welsh diaspora has so often produced some of our most fascinating literary figures.

Robert Jones was born in Llandderfel, Meirionydd (now a part of Gwynedd), in 1824. He received no education besides his chapel’s Sunday School, and at ten years old he ran away from home, first to Corwen and later to Llangollen. He worked through his teenage years in a range of odd-jobs in the industries of north-east Wales before, at nineteen years of age, leaving for England: Liverpool at first, then a period in London, before finally settling in 1850 in Manchester, the city in which he would live for the rest of his life and with which he is most associated.

This constant moving suggests something in his nature that was constantly striving for opportunities to better his situation, but also a willingness to go his own way when the situation called for it. Fascinatingly, when he left Wales he was a monoglot Welsh speaker – he would teach himself English over the next few years, and one can only imagine the kind of difficulties and prejudices he would have experienced as an exile, though of course there were Welsh-speaking communities in the cities he went to which would have helped him find work.

He began writing poetry around the time he moved to Manchester, becoming part of the city’s literary circle. Jones and his fellow poets decided to adopt the names of the places in Wales in which they had been raised as bardic names, and from then on Robert Jones, wIlliam Williams and John Hughes became better known as R. J. Derfel, Creuddynfab, and of course, Ceiriog, the most famous of all nineteenth century Welsh poets. Derfel won a number of minor prizes at various Eisteddfodau in the early 1850s and it looked like a fairly successful poetic career in a similar mode to Ceiriog was stretching out before him. Like so many prominent cultural figures in Wales he was also preaching. However, as it turned out, R. J. Derfel’s literary career would follow a very different path.

Political radicalism

19th century Manchester was a hotbed of political radicalism, and in the period Derfel lived there its residents included figures as prominent as Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Derfel came under the influence of these, among others – appropriately enough perhaps, his biggest philosophical and political influence was the Welshman Robert Owen (1771-1858), a prominent early figure in the history of radicalism. Derfel started lecturing and writing prose in Welsh and English on the work of these figures and the subjects that commanded their attention: workers’ rights, poverty, education, womens’ rights, and so forth.

Derfel became a bookseller and publisher, attempting to make his living by selling Welsh books and pamphlets. He still wrote poetry, but after the 1850s he abandoned the Eisteddfod, using his poetry instead as a vehicle for this political and philosophical views. This is the kind of poetry R. J. Derfel is most strongly associated with, as can be seen in poems like Cwyn y Gweithwyr (The Workers’ Complaint), Clywch, Gymry, Clywch! (Listen, Welshmen, Listen!) and Gruffydd Llwyd:

Os gwych yw gweld anheddau hardd

Yn britho tref a gwlad,

Pa beth yw’r cytiau wneir i’r bobl,

Ond trawster a sarhad?

Pa warthrudd mwy na bod y rhai

Sy’n gwneud palasau’r llawr

Yn gorfod byw mewn gwaelach tai

Na chŵn yr Yswain mawr?

[Though it is fine to see beautiful houses

up and down the country,

what are these hutches for the people

but injustice and insult?

What greater disgrace than that those

who build palaces on earth

must live in worse housing

than the big Squire’s dogs?]

Poverty, hypocrisy, social injustice, the treatment of women (especially those deemed to be ‘fallen’), even slavery: all these became the subjects of Derfel’s ire as expressed in his poems and songs. He was a Socialist of conviction, even a Communist – he used both terms, though his political program was one of reform more than revolution. Nevertheless at times there is a genuinely revolutionary character to his verse which cannot be found in almost any other Welsh poetry of the period:

Mae dydd o ddialedd yn nesu,

Yn nesu, yn nesu o hyd;

Dydd pwyso a barnu gweithredoedd

Anghyfiawn gorthrymwyr y byd:

Dydd codi y bobloedd i fyny,

A thaflu ysbeilwyr i lawr

Dydd cosbi segurwyr diddefnydd,

A llwyddo llafurwyr yn fawr.

[A day of vengeance is coming,

Closer, closer all the time;

A day when measured and judged shall be

The unjust actions of the world’s oppressors;

A day when the people will rise up

And throw down the plunderers

A day when the useless and idle will be punished

And great the success of the labourer.]

Pioneer

It was not only economic matters with which Derfel concerned himself. If he is one of the pioneers of Welsh Socialism then he is also one of the pioneers of Welsh Nationalism. It is interesting and significant that despite all the international influences that were working on him, he never turned his back on the Welsh language nor the importance of the country in which he had been born, though he had spent so little of his adult life there. In a period when so many were questioning the relevance and purpose of Welsh – even those who professed to value its literature – Derfel never stopped fighting the language’s corner, and clearly associated the language with national revival:

Tra syllwn ar y geiriau hyn,

Daeth sain ymchwyddol dros y bryn

A cyn y sain mi dybiwn fod

Syniadau gwlad yn ceisio dod

O rwymau trais yn rhydd;

Ac wrth glustfeinio tua’r lle

Mi glywn lais fel taran gre’

Yn bloeddio yn Gymraeg i gyd

Y geiriau glywyd gan y byd

“Cymru Fydd, Cymru Fydd!”

[Whilst looking at these words

A growing noise came over the hill

And before this noise I supposed that

The ideas of a nation were attempting

To free themselves from the bonds of oppression;

And whilst listening

I heard a voice, like a great thunder

Yelling in Welsh

Words heard the world over

“Cymru shall be, Cymru shall be!”]

In his prose he argued in favour of education in Welsh and establishing national institutions for Wales, including a university and national library, long before any of these things existed. It was R. J. Derfel that coined the phrase Brad y Llyfrau Gleision – the Treachery of the Blue Books – to refer to the 1847 Report into the state of education in Wales: it was the title he used for a verse play which he wrote in response to the report, though the papers at the time refused to publish it for fear of causing offence. Derfel went on to publish it himself in 1854.

Regardless of his other influences, it was clear that Derfel’s Socialist views derived at least in part from his Christian faith. When he moved to Manchester he was preaching with the Baptists, and among his poems are a number of hymns some of which are still sung in Welsh chapels. In one of them in particular, Dragwyddol Hollalluog Iôr, we see his usual radical message expressed in the devotional context of a hymn:

Dragwyddol, hollalluog Iôr,

Creawdwr nef a llawr,

O gwrando ar ein gweddi daer

Ar ran ein byd yn awr.

Yn erbyn pob gormeswr cryf

O cymer blaid y gwan;

Darostwng ben y balch i lawr

A chod y tlawd i’r lan.

[Eternal, omnipotent Lord,

Creator of heaven and earth

Oh listen to our fervent prayer

On behalf of our world.

Against each mighty oppressor

Take the part of the weak

Throw down the prideful head

And bring the poor to the shore.]

Agnosticism

However, as the century wore on Derfel began to distance himself from the church and in some of his prose he was one of the first thinkers in Welsh to explore agnosticism, and morality outside the Christian worldview, though we get only the occasional hint of this in his poetry.

Like many radicals, Derfel was not always well received by his countrymen. His bookshop in Manchester failed, and in the last decades of the century he wrote less poetry and less in Welsh, though he still contributed articles to the Welsh press, often using the pen-name ‘Socialist Cymraeg’.

The significance and value of R. J. Derfel’s poetry arises mainly from its content: he stands to a great extent outside the mainstream of Welsh poetry of his age, though his influence can be seen in the work of later poets like T. E. Nicholas, and radicalism would become a far more obvious aspect of Welsh poetry in the twentieth century. Derfel’s verse could justly be criticised for a lack of subtlety and the vast majority of his poetry takes the form of rhyming couplets, which can become repetitive, though one senses that he was making a deliberate attempt to appeal to ordinary, uneducated readers with catchy and appealing songs and poems. At his best, his poetry is witty, direct and powerful.

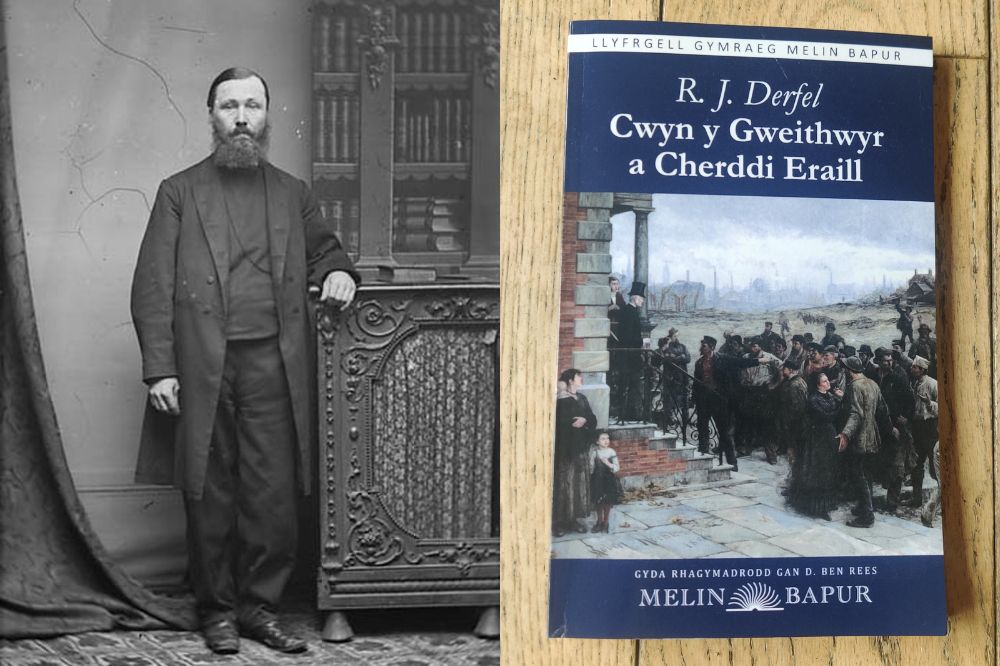

R. J. Derfel is an exceptionally interesting character, and in our new publication of a volume of his poetry – the first book of the author’s poetry to be published since the nineteenth century – we have included an introduction by D. Ben Rees, author of Cyd-ddyheu a’i Cododd Hi: Hanes y Blaid Lafur yng Nghymru (a history of the Labour Party in Wales).

A version of this article originally appeared in Welsh on www.melinbapur.cymru

R. J. Derfel’s Cwyn y Gweithwyr a Cherddi Eraill – The Workers’ Complaint and Other Poems – is available now from www.melinbapur.cymru priced at £7.99+P&P. Also newly published this week is a new edition of T. Rowland Hughes’s classic novel O Law i Law, priced at £10.99.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Difyr iawn. Diolch, Adam. So easy to forget these people

Diolch yn fawr.