The first Welchman in Japan

Susan Karen Burton

In the summer of 1619, three sailors lay chained in the hold of Dutch sailing ship, The Angell. Captured in a sea battle between the Dutch and the English off the coast of Java, they had been transported as prisoners to Japan.

On the journey they were beaten, tortured and shackled beneath a waste pipe. The ship had dropped anchor in the middle of the bay of Hirado, a thriving trading post in the west of Japan, north of Nagasaki.

Observing The Angell from the shore was Richard Cocks, an employee of the East India Company and head of Hirado’s English factory, a trading post housing the wares of the Honourable Company.

Cocks had arrived in Japan in 1613 aboard The Clove, the first English ship to make landfall in the archipelago. When The Clove had departed six months later, Cocks and six merchants had been left behind to promote trading opportunities with the Japanese.

A lack of subsequent ships, the poor quality of their cargoes, and Cocks’ own preference for cultivating his vegetable garden over chasing sales opportunities, meant that the English factory’s fortunes were suffering, especially compared to the Dutch factory nearby.

Cocks made no attempt to rescue the sailors on The Angell. But someone else did.

The crew of The Clove were not the first Englishmen to set foot in Japan. Kent native, William Adams had arrived ten years earlier as the pilot of a Dutch vessel. Adams had narrowly escaped execution when the shogunate, the military leaders of Japan, realised his worth.

Not only was he an expert pilot but he had previously trained as a ship builder. Now fluent in Japanese language and customs, Adams was also of great use to the men of the East India Company although they remained distrusting of his motives, suspecting he had gone native. But one sultry August night, Adams crept aboard The Angell and rescued two of the captured sailors.

Hugh Williams

The Dutch were incensed at the loss of their hostages. Such a daring feat could not be repeated. Yet the very next night, Adams climbed back aboard and freed the third man. Recounting this second rescue in a letter to the Company, Cocks noted that the third prisoner was a man called Hugh Williams. And he was ‘a Welchman’.[i]

This is the first documented evidence of a Welsh native setting foot in Japan. But Williams probably wasn’t the first Welsh sailor to step ashore in the archipelago.

The early seventeenth century was a period of European exploration and expansion. The East India Company financed voyages in search of valuable and exotic cargoes: cotton, silk and tea from India, and pepper, cloves and nutmeg from the Spice Islands. Japan was viewed as a potential market for English products – calicoes, broadcloths, tools – which they could exchange for the country’s rich deposits of silver.

The 527-ton Clove had carried not only Richard Cocks but also a ship’s company of sixty-three men, including a Thomas Jones, ship’s baker, and a Christopher Evans, gunner’s mate.

Brothels

We know something of them because their behaviour in Hirado was noted in letters and the ship’s journals. Jones was caught trying to swim ashore at night to visit ‘base baudye places’ (brothels and drinking houses). Evans swam ashore repeatedly until he was dragged back and set in the ‘bilbowes’ (shackles).[ii] He later absconded into the Japanese interior with six other crew members and was never seen again.

It is possible that Jones and Evans were also Welsh, although we can’t be sure because – with Wales having been unified with England under King Henry VIII – Welsh sailors were considered to be ‘English’ and listed as such on crew lists. But Wales is a sea-faring nation and there can be no doubt that Welsh sailors were involved in the East India Company’s first forays into Japan.

Wales has a long and continual history of migration. Welsh settlers have established settlements throughout the world, including farming villages in Canada, mining communities in the Ukraine, and Y Wladfa, the Welsh colony in Patagonia.

It is therefore no surprise that, four hundred years after Hugh Williams, Welsh citizens are continuing to travel to Japan and many are choosing to remain, some for a short time, others for life.

As an oral historian with an interest in migration studies, I have spent many years recording interviews with foreigners who live and work in Japan, discussing their lives, their experiences, and their feelings about home, wherever that may be.

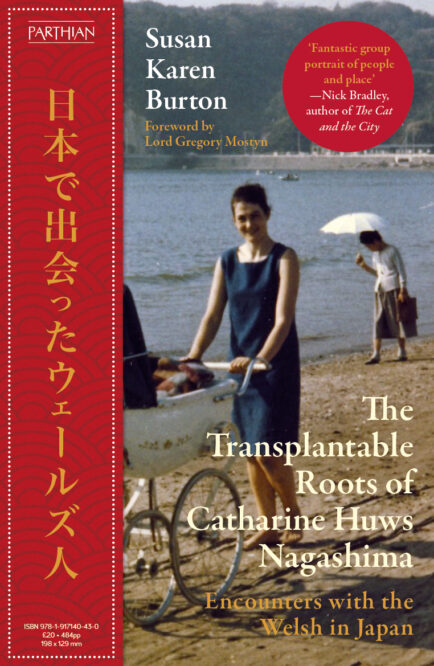

In 2015, I travelled to the seaside resort of Zushi to meet a lady called Catharine Huws Nagashima. Sitting on tatami (rush matting) and sipping green tea, Catharine talked about hiraeth and the importance, despite sixty years living in Japan, of her Welsh roots.

My account of the visit, The Transplantable Roots of Catherine Huws Nagashima, won the New Welsh Writing Awards Rheidol Prize and I was commissioned by New Welsh Review’s book imprint New Welsh Rarebyte to seek out more Welsh residents in the archipelago.

Unfortunately, Britain had just gone into Covid pandemic lockdown, and Japan’s national borders were closed. No travel was possible. But there is a Japanese proverb which advises anyone planning a course of action to, ‘sit on a rock for three years’ (ishi no ue (ni mo) san nen). It means ‘to be patient’.

Vaccinations

Exactly three years later, with the requisite three vaccinations and the support of a Daiwa Foundation grant, I was able to return to Japan to further interview its Welsh residents, to visit their homes and businesses, and to hear and record their stories.

Encounters with the Welsh in Japan features fifteen stories of Welsh men and women who have spent an extended time in Japan. Although many of them initially moved to the country to teach English, either on the Japanese government’s Exchange and Teaching Programme (JET) or for eikaiwa (private English language conversation schools), I have concentrated on those who are following other interests, either full-time or as a hobby.

I have tried to cover a wide range of lifestyles and interests, using interviewees lived experiences to highlight aspects of Japanese culture as well as the joys and frustrations of everyday life as a gaijin (foreigner).

Naturally, I also questioned them about their Welsh roots, their feelings about the concept of home and of hiraeth. Whether by design or accident, the majority of my interviewees could speak Welsh as well as English on departing Wales, a feature which in itself gave rise to interesting themes of language, identity, cultural sensitivity and ease of assimilation. I have also included themed extracts from many more interviews, to give voice to all the Welsh people I met on my journey.

According to Japanese population statistics, there are 19,040 citizens of the UK currently living in Japan: 14,005 male and 5,035 female. While there is still no record of the number of Welsh included in these figures, if we estimate a figure based on the percentage of the UK population who are Welsh (4.5 per cent) that figures comes to 857. The majority of these will be English language teachers who are likely to remain in the country for little more than a year or two.

I estimate that there are probably two to three hundred Welsh living long-term in Japan. That number may be higher, however, because Wales and Japan share a more recent history, and one which may have encouraged a higher percentage of Welsh to feel close ties to Japan.

Job losses

In the early seventies, with the decline of the Welsh steel industry and the closing of the coal pits and resulting job losses, the Welsh Development Agency sought to attract large scale Japanese manufacturing.

The 1964 Tōkyō Olympics signalled Japan’s recovery from almost total destruction in the Second World War. As it entered a period of high economic growth, Japanese companies sought to establish overseas factories to meet the global demand for Japanese goods.

Takiron, which made PVC corrugated sheeting, was the first company to open a factory in Wales, in Bedwas, Gwent, in 1972. Hitachi (Hirwaun), Sony (Pencoed and Bridgend), Panasonic (Cardiff, Gwent and Port Talbot) and many others soon followed, their factories primarily manufacturing consumer electronics such as televisions and video cassette players, of which Japan was a pioneer at that time.

By the eighties, at the height of Japan’s manufacturing capacity, Wales hosted the largest concentration of Japanese electronics companies outside Japan and the United States.

Many of the interviewees in this book have strong childhood recollections of the Japanese presence in Wales. Interviewee Geraint M remembers growing up near the Sony television plant and seeing the Japanese expatriate families around town:

There seemed to be a Japanese community that arrived in the eighties. In the Rhondda there was a Burberry factory where they would make those Mackintosh things. And there was a factory shop.

So, of course, you would see the Japanese couples who were obviously buying gifts, stocking up on the omiyage (souvenirs) from Burberry to take them home.

Ursula Bartlett-Imadegawa recalls the impact of Japanese management practices on the Welsh workforce:

I can remember as a young girl watching the television, and the fascination with the new Japanese companies that came in. I can remember the newscaster interviewing this [Welsh] guy and he said, ‘They have lunch with us in the same canteen. None of this “tablecloth in another room and the bosses over there”. No, they eat the same as us.’ And [he also] said, ‘We couldn’t believe it, they were moving something in and we suddenly realised it was a couple of ping pong tables. And then the boss turned up and played ping pong with us.

This lack of segregation proved popular, particularly with former miners, as it mirrored the close teamwork necessary to ensure safety in the pits. Lacking a class-based hierarchy, it was also standard procedure in Japanese companies for blue collar workers, with the right training and attitude, to be promoted into management.

Welsh workers could also profit from in-house training, which showed Japanese companies’ commitment to employing workers long term. Expertise in factory floor practises such as kaizen (continuous improvement) and 5S workplace organisation – sort, set in order, shine, standardise and sustain – made welcome in other industries those Welsh workers who had been trained by Japanese companies.

The Japanese presence in Wales in turn stimulated exchange programmes, which gave some interviewees their first encounter with the culture.

Translator Gareth Jenkins began learning the language at secondary school when Ceredigion County Council employed a Japanese teacher. He later did a two-week homestay in Japan, funded by the Aberystwyth–Kaya Friendship Association, a group started with the support of Frank Evans who had been a prisoner of war in Kaya during the Second World War.

Gareth went on to study business studies with Japanese at Cardiff University before joining the JET Programme in 2001.

Several Welsh universities offer Japanese language and/or business studies courses, and some interviewees took advantage of these. Like Gareth, public relations consultant Abby Hall also studied Japanese and business at Cardiff University, then stayed on for a master’s degree in Japanese translation before moving to Japan and establishing a career in public relations.

The global popularity of Japanese consumer electronics was swiftly followed by a wider appreciation of its arts and entertainments, which also played a part in tempting its Welsh fans to move to Japan. St David’s Society Japan’s president, Ursula Bartlett-Imadegawa discovered ukiyo-e woodblock prints and kabuki classical theatre in her Cardiff fifth form class, which led her to accepting a teaching post at an international school in Tōkyō.

Video game localiser Geraint Howells grew up playing Japanese video games and now works for Nintendo. As a child, JET Programme participant, Bethany Jo Cummings’ love of Studio Ghibli movies led to her hiring a private teacher so that she could take ‘A’ Level Japanese in Porthcawl.

Film writer/director/producer John Williams moved to Japan because of his love of Japanese arthouse movies. Teacher Eddy Jones first met CW (Clive William) Nicol at the Kotatsu Anime Festival in Wales where the environmentalist was promoting an anime (animated film) inspired by Afan no Mori, his forest in Japan. Ex-Cardiff nightclub bouncer Jaime Morrish was pulled to Japan by his black belt in jiu jitsu. Teacher Gerald Gallivan and Abby Hall both sport Japan-inspired tattoos (which ironically causes them problems in Japan).

Cultural exchanges work both ways. The Transplantable Roots also features interviews with three Japanese citizens who spent time in Wales and who, through the St David’s Society Japan, keep the Welsh spirit alive in their homeland.

President of the St David’s Society Japan’s Kansai branch, Chikako Hirono, spent six months teaching Japanese language and culture at a primary school in Cardiff. Dr Takeshi Koike teaches Welsh at his Tōkyō university, a language he first encountered on a one-year exchange programme in Lampeter.

Former radio disk jockey, Yūko Nakauchi took a summer Welsh language programme in Lampeter and returned to study for an undergraduate degree in media studies, in Welsh.

When Japan fell into recession in the early nineties, some Japanese factories in Wales closed or moved their operations elsewhere. But there are still sixty Japanese-owned companies in Wales today, and Japan continues to exert a strong economic and cultural influence on Welsh people.[iii] For many of the interviewees in this book, the seeds of interest in Japan were planted back home in Wales, and for many, that contact has been life changing.

I would like to express my deepest thanks to the interviewees in this book who opened their lives and homes to me, and who answered my constant and intrusive questions with infinite grace and patience.

Shortly after winning the New Welsh Writing Awards, I zoom-called Welsh freelance journalist, Lily Crossley-Baxter. It was during the Covid pandemic lockdown, and she was living in – and largely confined to – a shared house in the Tōkyō suburbs. ‘Would enough Welsh people want to speak with me about their lives in Japan?’ I wondered.

‘I reckon they would,’ she answered. ‘What’s that saying? There’s no better Welshman than a Welshman outside of Wales? They bloody love talking about it.’

They did bloody love talking about it. And I am grateful to all of them.

[i] Reference to a ‘Welchman’ is from Richard Cocks’ letter to Sir Thomas Smythe and the East India Company in London, dated 10 March, 1620, in volume 1 of The English Factory in Japan 1613–1623 by Anthony Farrington (British Library, 1991), p785.

[ii] The antics of Thomas Jones and Christopher Evans are noted in Farrington volume 2 which contains extracts from John Saris’ journal of the voyage to Japan in 1613, p995-6, and in Samurai William: The Adventurer who Unlocked Japan by Giles Milton (Sceptre, 2005 edition), p180.

[iii] Figures on Japanese companies in Wales taken from the website: tradeandinvest.wales

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Welchman??

That is how they spelt it then,live with it pal.