The Gannets of Grassholm, Part 3: The World Comes to the Pembrokeshire Bird-Islands, Sunday 8 July 1934

Howell Harris

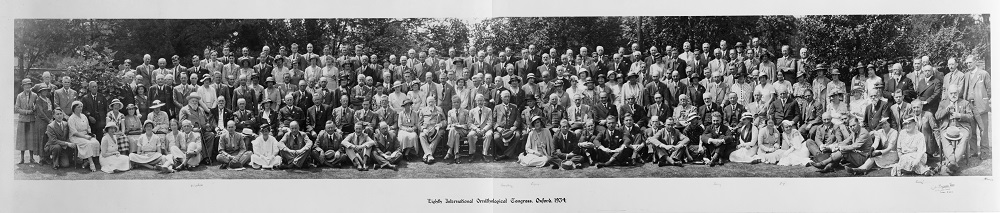

In July 1934 the International Ornithological Congress, one of the oldest international scientific meetings in the world, was scheduled to be in Oxford – only the second time the IOC had come to Britain in its fifty-year history.

Europe and North America provided the bulk of members and delegates, but most developed nations and some of their larger colonies were also represented by government scientists, leading academics, and committed amateurs.

Altogether, about 350 people from 25 countries would turn up for a week of scientific papers, receptions, business meetings, an art and photography show, wildlife movies, and excursions, staying in college accommodation and using university buildings.

Long excursion

One of the IOC’s traditions was the “long excursion” at the end of Congress. Host countries aimed to show their foreign guests the best that they had to offer.

And the British local organizing committee decided in 1933 that Britain’s finest ornithological wonder within traveling range of Oxford was the Pembrokeshire bird-islands, where the breeding season would be in full swing.

Ronald Lockley’s publisher Harry Witherby was a key member, and he steered its choice towards a place about which he was as enthusiastic as Julian Huxley.

The islands offered “a wealth of sea-bird life in a comparatively small compass,” and Lockley, Witherby’s protégé, already “well known for his ornithological researches, was resident on Skokholm and fully prepared to give every assistance.”

Sociability

Witherby and his wife took charge of the practical arrangements. Transporting delegates the 200 miles from and to Oxford was easy: they hired a small fleet of motor coaches and arranged scenic refreshment stops.

The trip was slow, but the sociability it fostered was ample compensation. Accommodation was not a problem either: enough decent hotel rooms were available to book in the small resort town of Tenby.

Almost half of the delegates chose to come, paying £7 per head (the equivalent of about £1,500 nowadays) for the experience.

Huxley gave them a taster of what they were about to see by showing his recent footage of the Grassholm gannets to an appreciative conference audience.

But for the all-important islands tour itself there were no suitable ships available to hire, though Lockley and his Cardiff friend Morrey Salmon tried their best with the proprietors of the Neyland-Pembroke Dock ferry and Bristol Channel pleasure steamers.

With time running out Witherby (a decorated naval officer in World War 1) and his organizing committee colleague Alec Wilson approached the Navy for help.

Former King

They argued that the Congress was of great international importance, with delegates from many nations and governments including – the clincher! – a person going by the name of Graf Murany, elected one of the Congress’s three vice-presidents.

The elderly (73) and doddery aristocrat was the former King Ferdinand I of Bulgaria, a keen and respected birdwatcher and the great-nephew of Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert.

The fact that Wilson, a retired Commander, was a close friend of another former naval officer who just happened to be the First Lord of the Admiralty at the time, Conservative politician Sir Bolton Eyres-Monsell, probably helped as much as the strength of their arguments.

So the Navy provided two destroyers, HMS Windsor and Wolfhound, which were conveniently carrying out “Meet the Navy” days at holiday resorts around the Welsh coast.

The IOC delegates were able to take the short train ride from Tenby to Pembroke Dock after an early breakfast (preceded by Mass for King Ferdinand), walk aboard ship, and enjoy RN hospitality as they cruised the 14 miles to Skokholm at up to 20 knots through calm seas and in magnificent weather. Seats and much-needed sun awnings were laid out for them on deck, and they were plied with free drinks.

Ferried ashore

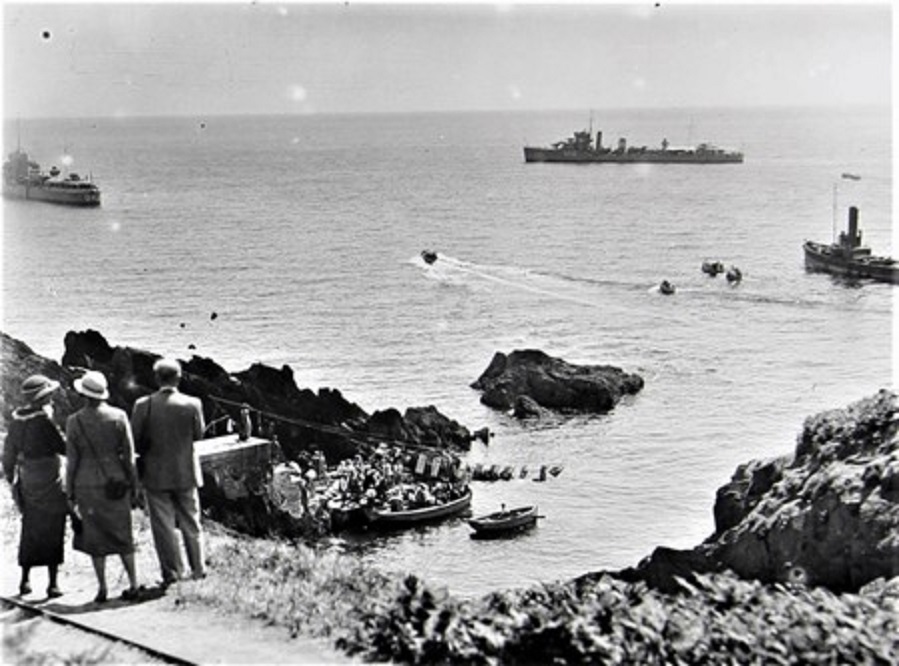

On arrival, happy passengers were ferried ashore quickly and safely at South Haven in the ships’ boats and also by my great-grandfather William Rouse and his sons’ old tug Taliesin, which could moor much closer in than the destroyers dared.

She was a quarter their length, half their draught, far more manoeuvrable, and her captain, my Great-Uncle William, knew the islands and the channels between them like the back of his hand, particularly after years of lighthouse relief trips.

So all of both destroyers’ boats could be used to transfer the Wolfhound’s passengers while the Tally served the Windsor as a tender, taking all of its passengers in one trip close enough for them to be rowed to and from the shore by my grandfather and his brothers in the Tally’s own boats, which you can see in this picture.

On the map

The Lockleys had prepared frantically, mostly at the last minute, for what their daughter Ann remembered as “the highlight of the year”, a “great honour for her parents” which “put Skokholm on the map as the first Bird Observatory in Britain.”

The island had gained this status in 1933 when the RSPB took over Lockley’s lease.

In 1934 he completed his transition from being an unsuccessful sheep farmer, rabbit trapper, and fisherman, loaded with debt after years attempting to be self-sufficient, into a rather better rewarded author and naturalist, the main careers he pursued for most of the rest of his life.

They decorated their cottage and the Haven with the flags of all nations represented at the Congress, borrowed for the occasion from a Milford shipping agent apart from a Nazi Swastika, not yet the only recognized national flag, which he did not have, so Doris Lockley ran one up on her sewing-machine.

They put up notice boards to bird colonies and nest sites, led groups of visitors to places of special interest, and explained the ornithological research which was now Lockley’s main activity.

Ex-King Ferdinand, heavy and wracked with gout, had great difficulty making it from the landing place even as far as the house, no more than a couple of hundred yards, accompanied at every step by an equerry carrying a stool so that he could rest, and also get down far enough to see into a convenient nest hole.

After lunch provided by the Lockleys, including a barrel of beer they had bought, and with more free drinks through the generosity of Commander Wilson, the visitors re-boarded their destroyers with the Taliesin’s help and cruised to Skomer, where the shore visits were repeated.

The Tally got there first by taking the dangerous direct route through Jack Sound rather than the safer one to the west and north of the island.

Special treatment

Ex-King Fedinand had yet more special treatment. He was taken in the commander of the Wolfhound’s launch on a tour around Skomer, Lockley at the helm “having the time of his life” and providing a running commentary on the island’s sights and bird-life wonders, to save the old man from further exertions.

Then the Navy served tea on the beach (and the Lockleys provided another barrel of beer) before delegates re-embarked for an evening cruise to Grassholm, and then twice around the island at just 5 knots as close inshore as safety allowed.

Spectacle

The eminent American ornithologist Margaret Nice provided the best description of this part of the trip: “when we drew near, it seemed as though the island were covered with new fallen snow. It was a marvelous … sight – acres and acres of the great white Gannets on their nests.”

Then the destroyers blew their hooters to drive as many birds into the air as possible. After the resulting spectacle they set course homeward.

But even then, the delights were not over: Windsor signalled to Wolfhound “Form line ahead to engage Puffinus puffinus puffinus,” the Latin name for the Manx Shearwater.

Thousands of them gathered on the sea in ‘rafts’, waiting for dusk before they flew back to their island burrows.

Lockley was on the bridge of the Windsor pointing out the flocks and directing the destroyers as they zig-zagged through them at up to 20 knots, putting up thousands of birds as they came close to each raft, and making some of the passengers feel distinctly unwell.

Final treat

It was the final treat of a memorable excursion — for Lockley, “a day of days”.

As another very satisfied American visitor reported, “the weather was perfect and the birds were on best behavior.” It had also been a very good party.

On Monday morning Lockley went home to clear up after the busy day. He had to cover and extinguish the small fires in Skokholm’s bone-dry vegetation that visitors had caused with their carelessly dropped cigarettes and matches, and find and return the lost handbag of the wife of Konrad Lorenz, the distinguished Austrian ethologist.

Newsworthy

Sunday’s events made it into regional and national newspapers and magazines. Even before the release of “The Private Life of the Gannets,” Pembrokeshire’s bird islands, and Grassholm in particular, were on journalists’ and editors’ radar. They were newsworthy, and provided excellent photo-opportunities.

The Saturday Times, for example, printed a detailed report from Lockley on the scheduled visit even before it had happened.

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News published a two-page article by Morrey Salmon who was, like Huxley, one of the official British delegates to the IOC as well as being a close friend and collaborator of Lockley’s and frequent visitor to Skokholm.

His article, full of his own excellent pictures – he was, after all, the ‘father’ of British wildlife photography – pulled no punches: Grassholm was, its title claimed, “Britain’s Most Amazing Bird Colony: Where Eggs and Nests Cover Acres of Island Cliffs and Fields.”

Its stable-mate the Illustrated London News also had a double-spread of Lockley’s and Salmon’s photos, with a similarly boosterish headline: “Wonders of the Remote Welsh Bird-Islands Visited by the Ornithological Congress.”

Extraordinarily generous

The Western Mail, Wales’s leading newspaper, even had its own special correspondent on board the Windsor, who wondered why the Navy had been so extraordinarily generous to the IOC visitors.

This question also troubled the Labour MP William Mainwaring, a coal miner, union activist, and recent victor in the Rhondda East by-election, given ex-King Ferdinand’s role as head of an enemy state during the Great War, still fresh in people’s memories.

Eyres-Monsell answered Mainwaring’s parliamentary question very diplomatically.

The journalist received a more interesting response from someone he talked to onboard: “perhaps it was in order to make some reparation for what occurred just over a quarter of a century ago when a number of cadets from one of the warships of the British Fleet landed at Grassholm and with sticks and oars wrought havoc among the birds. Questions were asked in the House of Commons about it and an inquiry followed.”

As we know, that had nothing to do with it. But the journalist’s anonymous source was not altogether wrong.

Something very bad had happened in the past, beyond the range of accurate memory but not so long ago as to have been quite forgotten, between members of the British armed forces and the seabirds, particularly the gannets, of Grassholm; and it had affected their subsequent history, and the ways in which they came to be appreciated as a rare natural wonder, in the following decades.

Author’s note: I should like to thank David Saunders, appointed first RSPB Warden of Skomer and Grassholm in 1960, for his invaluable assistance. He wrote an account of this occasion for the fiftieth anniversary in 1984, and deposited his research notes in the Pembrokeshire County Record Office. These supplied some information otherwise unavailable, and also Morrey Salmon’s wonderful pictures, printed by the photographer himself when he was already 90.

Parts one and two of the Gannets of Grassholm series can be found here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.