The Gannets of Grassholm, Part 4: The Whit Monday Massacre, 26 May 1890

Howell Harris

Grassholm slumbered quietly for centuries on its outer edge of Wales. Recent surveys and excavations confirm that the last time the island had any permanent human inhabitants was definitely prehistoric.

Sheep may have been brought over for summer grazing in the Middle Ages, and its seabirds and their eggs provided locals and passing fishermen with a regular harvest well into the twentieth century.

But in the nineteenth it was still so secluded that its rare appearances in the press had just two subjects: it was an occasional destination for summertime pleasure-trips by local passenger steamers; and it was a regular site of shipwrecks, partly because it never got the lighthouse it so clearly needed.

Nobody even seems to have paid much attention to its abundant wildlife, despite Victorians’ energetic interest in exploring the natural history of their own country as well as the rest of the world.

But in 1879 Samuel Williams of St. David’s, 15 miles across the sea and one of the best places from which to reach Grassholm by rowing or sailing boat, wrote a letter to The Field (“The Country Gentleman’s Magazine”) extolling the richness of his district, particularly its offshore islands and rocks.

There were “gannets…, breeding in numbers” on Grassholm, “and, as if Nature revelled in the panorama, there are other objects ready to claim excitement, curiosity, and sport.”

Atlantic Grey Seals, for example, could be stalked and shot, or clubbed to death when they came ashore in breeding season, and their pups “taken alive, and fed by hand” until they could be sent to collectors inland. Porpoises and sea otters could also be shot and skinned. This was one educated Victorian gentleman’s quite conventional way of enjoying the bounty of Nature with which his locality was so amply bestowed, and recommending it to others.

Popular ornithology

However there was another, increasingly popular way of approaching wildlife, particularly birds, that involved neither killing nor even collecting, but instead simply observing and admiring.

Just as the development of the breech-loading shotgun and mass-produced cartridges helped turn the late nineteenth century into an age of murderously efficient bird slaughtering, and the railway and postal systems helped promote the egg-collecting and taxidermy crazes of the time, so too the increasing availability of good, inexpensive, and lighter binoculars and cameras encouraged a new style of quieter, less destructive popular ornithology.

Four Cardiff men who landed on Grassholm on Whit Saturday, the 24th of May 1890, all shared this new style.

They came to enjoy the peace, isolation, and natural beauty of the place as a break from their busy lives in the booming coal metropolis.

They were all members of the city’s business and professional class and also of the Cardiff Naturalists’ Society, a couple of decades old and with several hundred members already.

This was the local example of a nationwide Victorian phenomenon, the “field club,” which had turned the appreciation of natural history into a mass-participation social movement.

Rarity

The idea for their trip came from Joshua J. Neale (36), a fish merchant and trawler owner.

One day when he was visiting Milford Haven a friendly fisherman who knew of his interests told him that he thought there were gannets on Grassholm, and definitely plenty of other seabirds.

Gannets had become a rarity in the Bristol Channel since the decimation of the centuries-old colony on Lundy, 45 miles to the south, in previous decades.

So, he decided to go to Grassholm and see them for himself.

As he put it in a lecture delivered a few years later, “I delight in quiet holidays. What noise there is I prefer to be of the sea dashing on the rugged rocks of some out of the way island or the interesting noises and calls of the numerous seabirds on those islands … On these islands you have absolute freedom and also quiet in which to observe the habits of the many birds and few animals which inhabit or frequent them.”

He thought the purpose of life was to have “an enjoyable time to spend in the world and see as far as possible the beautiful and interesting things in it,” rather than just to make money, though he had plenty of that too.

He was not absolutely opposed to collecting, but discouraged it among his fellow Naturalists as much as he could, particularly where it depended on trade.

“What will you ever learn by purchasing from dealers? You are helping to exterminate the rarer sorts of birds and animals. Go and observe the birds in their native haunts. It is better to observe and know the habits of even one common bird than to purchase stuffed specimens or eggs of a dozen of the rarer kinds. One is a question of intelligence, the other of cash.”

Pencil and brush

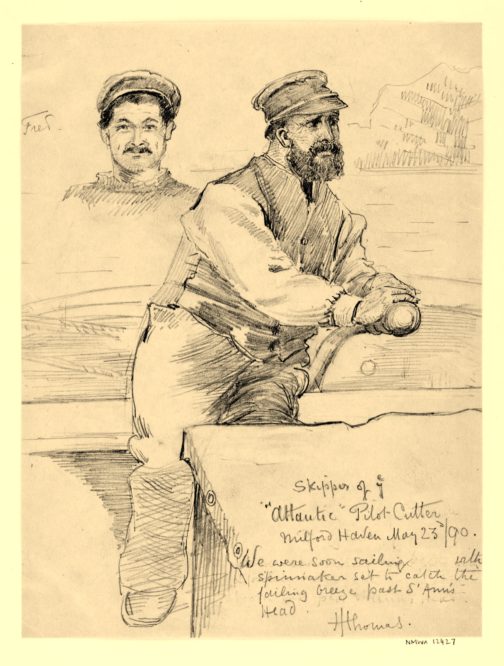

The three other members of the party were Thomas Henry Thomas (51), an artist and illustrator; Henry West, Neale’s partner; and Thomas W. Proger (30), director of sheep and cattle ranches in the Falkland Islands, Patagonia and Brazil, and a keen ornithologist.

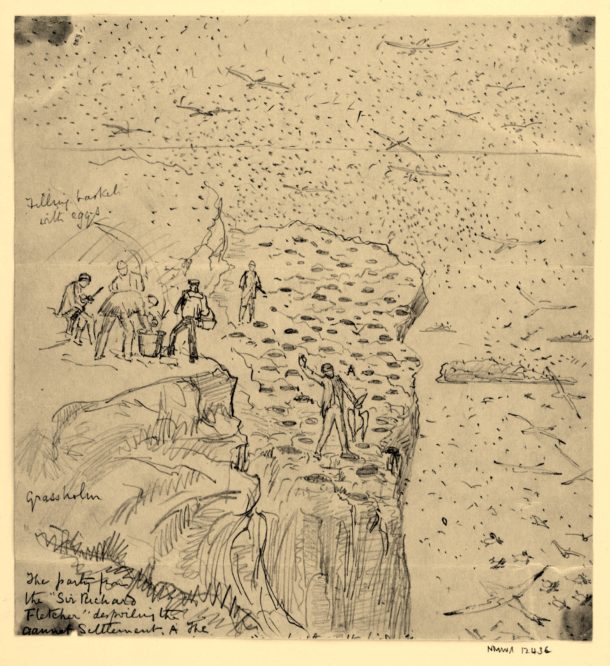

Fortunately, because of Thomas’s skill with his pencil and brush as well as his pen, and Neale’s own account, we have a detailed record of their visit.

They set off from Milford Haven on the afternoon of Saturday the 24th, with a pilot cutter and its expert crew to sail them out to Grassholm.

The island has no harbours or beaches, so landing is only possible, even nowadays, in quite calm seas, and usually involves scrambling onto wet rocks.

Myriads of seabirds

As Neale recalled, “This landing was one of those scenes which one never forgets. It leaves a pleasant memory which always recurs when one thinks of Grassholm. A beautiful spring, almost summer, night; the dark mass of (to us) unknown rocks up which we were to climb and drag our things: the myriads of seabirds with all their interesting and strange cries of alarm and protest against our invasion of their island home; the splendid expectation of what we should see at daybreak in the morning, made it altogether a sort of wonderland.”

Puffin burrows

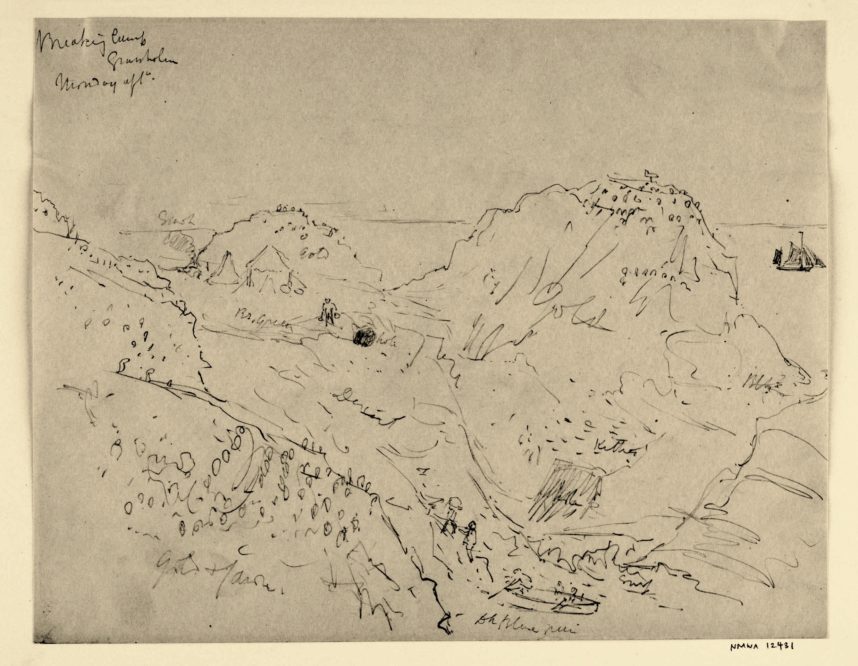

The naturalists’ party made their disembarkation even more difficult by arriving at nightfall because light winds had slowed their crossing.

They then had to offload the baggage and supplies for their camping trip from the cutter into a small boat, row it to land, and haul it up a gully to one of the few fairly flat places on the island where a tent could be erected, i.e. there was enough soil to drive the pegs in but it wasn’t covered in birds’ nests.

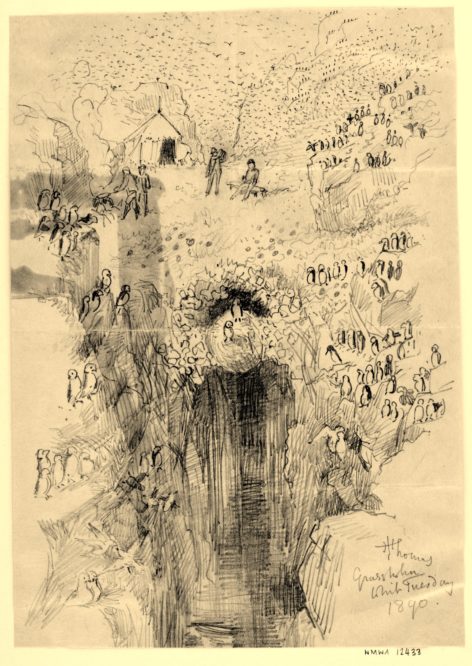

Thomas’s sketch shows how close the nesting birds were to the camp site. What it does not show is something they only discovered in the morning: they had actually pitched their tent on top of puffin burrows.

Disaster

Grassholm at the time was home to an (over-) estimated half a million puffins, a population density measured by another Cardiff Naturalists’ party three years later as up to 20 birds to the square yard.

Gannets were comparatively few – about 200 pairs, a number that had increased from just a dozen over the previous two decades.

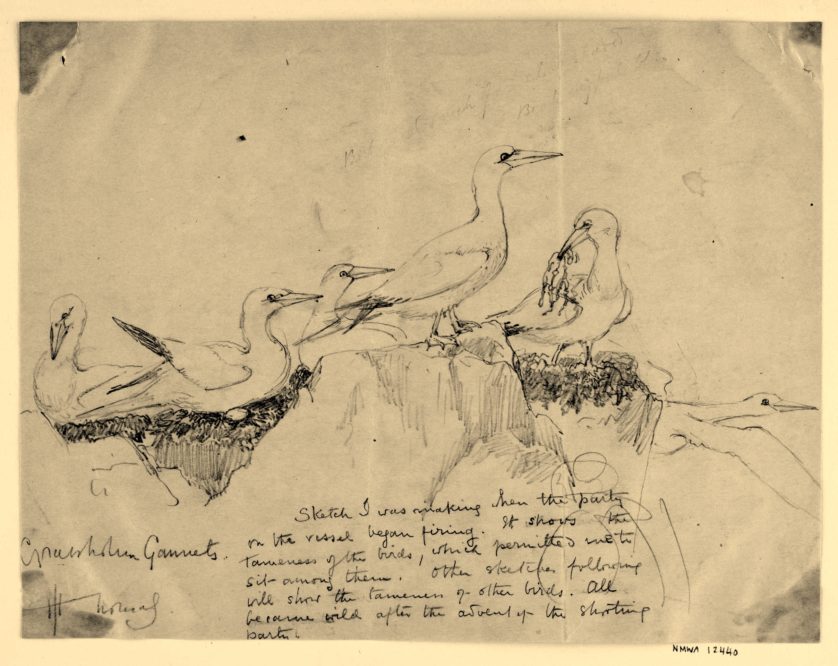

A day of enjoyment followed, with Thomas producing several sketches of birds that were so unafraid of man that they allowed him to get very close. He was “delighted with this foretasting of the millennium.”

Neale thought that the gannet colony by itself “was worth the whole of the trouble we had taken, to have this beautiful sight of these large snow-white birds on their nests.”

But this sketch of it was the last that Thomas could make before disaster struck.

Disturbed water

When he got back to his Cardiff studio he had the material to turn into a large (6’ x 4’) oil sketch of the small Grassholm gannet colony, just 200-odd nests on the tops of two small cliffs.

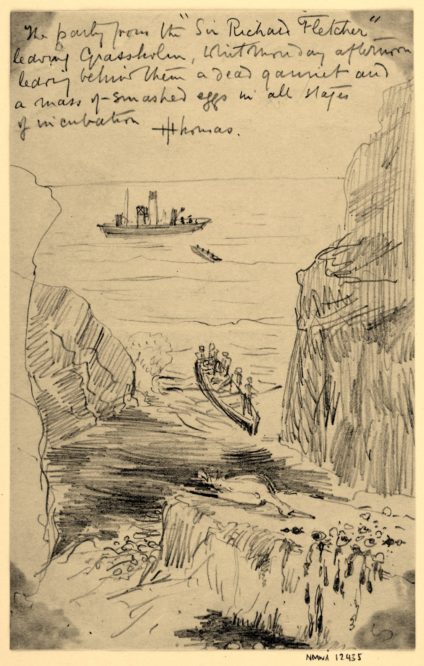

But in the background you can see a little ship, and a patch of disturbed water on the sea.

The ship was the Sir Richard Fletcher, a small (100 tons) War Office steamer, operated by a crew of Royal Engineers, members of the 35th Company of the Submarine Mining Service, based near Pembroke Dock and dedicated to the defence of the Royal Dockyard there and the Milford Haven waterway leading to it.

Insensate practice

The ship hove to and the men aboard started to amuse themselves by shooting at the birds on the cliffs – gannets, large and brilliantly white, made particularly tempting targets – but stopped when Thomas, who thought it was “an insensate practice,” signalled to them because their bullets were hitting quite close to him.

So, they changed to throwing small explosive charges into the sea to stun or kill fish, which they could then scoop up after they floated to the surface.

The patch of disturbed water on the sea in Thomas’s oil sketch is probably a representation of one of these explosions.

Wreak havoc

Worse was to come. The ship put down two boats, which rowed ashore and landed a party of men who commenced to wreak havoc.

The younger men shot puffins and hunted them out of their holes; while “three men in the costume and with the accent of gentlemen” (or, as Neale put it, “calling themselves gentlemen”, emphasis added) robbed the nests of the gannet colony, two of them taking a basketful of eggs back to their boat while the other smashed or chucked the rest.

Thomas was appalled: “I should have thought the man a maniac were it not that his companions were looking on, with apparent complacency, at his doings.”

Two eggs

The Naturalists did not interrupt or remonstrate with the hunting party – in fact, they went back to their tent for refreshments – but after the killers had left with their haul they checked the gannetry and found just two eggs left on 200 raided nests.

The smashed eggs had been “in all stages of incubation.” A breeding season had been almost wiped out, they thought.

It was, according to Thomas, “one of the most brutal scenes I have ever witnessed.”

Read the previous installments of the Gannets of Grassholm here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.