The Gannets of Grasshom, Part 10: Aftermath – a Happy Ending?

The tenth and final episode of the remarkable history of the Gannets of Grassholm reflects on how the network of protections which evolved following the terrible events of 1890 have helped make Grassholm the third largest colony of northern gannets on Earth, and how those protections are still needed to recover from the latest threat to their survival.

Howell Harris

When the excitement of the summer of 1890 was behind him, Thomas Thomas gave a talk about the fateful visit to Grassholm to the Cardiff Naturalists.

It was well received, so in the summer of 1891 he published it as an illustrated pamphlet.

As the South Wales Daily News put it, in a very positive review, “The notorious egg-destroyers from H.M.S. Sir Richard Fletcher are now hopelessly immortalised.”

He and his colleagues did far more to save the gannets than just speaking and writing about them. The future that faced Grassholm’s gannets, unless they took some action, was obvious to the Cardiff Naturalists.

They only needed to look across the Bristol Channel to the island of Lundy, site of a large and famous gannetry since at least the thirteenth century, and generally reckoned by Victorian ornithologists to be the original source of the much smaller and quite recent colony of refuge on Grassholm 40 miles north.

As a visitor in 1900 observed, “The history of the Gannets on Lundy is not pleasant reading for a lover of birds.”

Lundy was much more accessible than Grassholm, had a sizable resident population, and when tourists and egg-collectors joined the traditional harvesters of gannets and their eggs for food and other purposes, their numbers went into steep and irreversible decline.

Disturbance

The problem was understood as early as 1843, the ornithologist William Yarrell writing that “when the birds are suddenly and wantonly disturbed by the firing of a gun close to their breeding-places, the eggs may be seen to fall in showers, … where this disturbance, in order to show the number of rock-birds, is one of the amusements of the gaping tourist.”

Despite Lundy’s proprietor’s best efforts, understandably few birds succeeded in rearing their young, and they gradually retreated to the most isolated cliffs at the northern end of the island.

Then Trinity House decided to build a new lighthouse there, and the disturbance of blasting and construction work, followed by flashing lights every night and frequent blasts of the foghorn, destroyed their last refuge. By 1909 they were extinct.

The real threat of extinction, whether of a colony or an entire species, had been a strong motivating force for bird protection nationwide since the 1860s.

The awful example of Lundy, and the experience of the 1890 Grassholm Massacre, continued to influence the Naturalists for years.

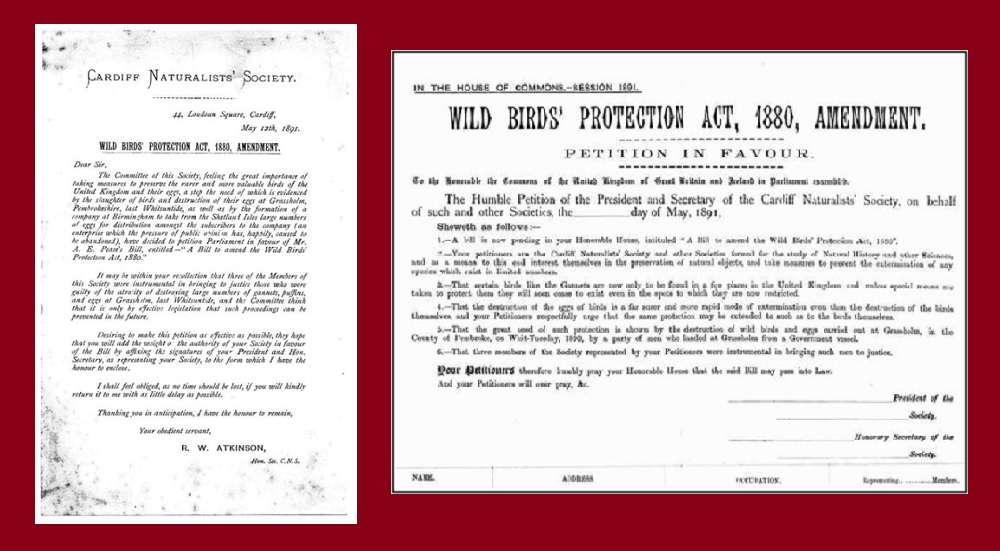

They learned from their experience of the RSPCA’s prosecution of the Sir Richard Fletcher’s men under the 1880 Act, and threw their weight behind a campaign to amend and extend it.

Its greatest weakness was that it was just about killing and trapping birds, with “no provision for preventing the extermination of rare and interesting species by the taking or destruction of their eggs.”

Petition

A bill to deal with the issue had been introduced in Parliament by Alfred Pease, Liberal MP for York, with bipartisan backing, in February 1891. But it had got nowhere.

So the Cardiff Naturalists took their case to other societies, seeking their support for a petition to Parliament, and to the British Association for the Advancement of Science, which met in Cardiff in August 1891, with Thomas playing a leading role.

The Association had by then two decades of experience as the coordinating, representative, and consultative body through which naturalists influenced parliamentary legislation on the protection of birds.

Through it they were able to help the friends of wildlife protection in Parliament relaunch their proposals for a new law.

The resulting Act finally passed both Houses and received Royal Assent in July 1894.

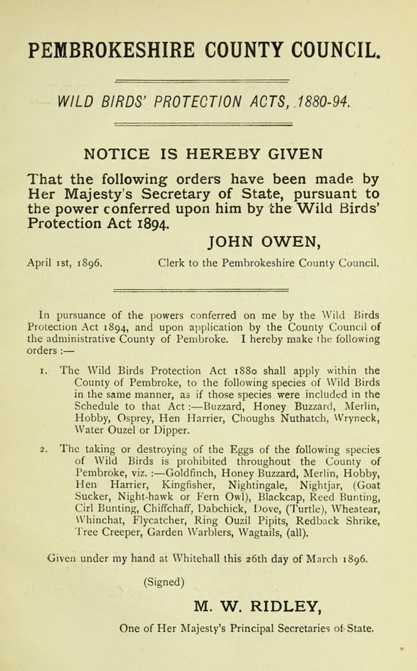

Once that had happened, the Naturalists lobbied county councils in their region to implement it.

Pembrokeshire’s willingly obliged, extending its coverage beyond species, like gannets, explicitly included within the act’s protection, to embrace other endangered species too.

Legal protections

Improving the framework of legal protections for gannets and their eggs was relatively easy to achieve. Actually protecting them was much harder. Ironically, the publicity Grassholm’s gannet colony gained in 1890 made the task more difficult.

As Joshua Neale reported, the summer’s events “called attention to this interesting bird island and dealers swooped down on it, egg collecting or employing fishermen to collect for them.”

Grassholm’s gannets also made their way into the growing literature of British ornithology, notably Murray Mathew’s The Birds of Pembrokeshire and Its Islands (1894), and even tourist guidebooks.

The result was increasing human disturbance, including from the Cardiff Naturalists themselves, who made regular return visits. So the number of nesting birds only grew slowly, to about 300 pairs by 1905, with a big setback in 1898 from another large egg-raiding attack that took everything.

After that, because of continuing unauthorised visitors, Neale complained that “scarcely any young birds reached maturity.”

It required a summer of bad weather, preventing landings, to produce a single good breeding season.

Unexpected help

But there was some help from an unexpected quarter. In 1892 the tenant of Skomer and Grassholm since 1861, Captain Vaughan Palmer Davies, a relative of Major Henry Warren Davies who had always considered his wildlife primarily as a source of sport and profit, and had even grazed sheep on Grassholm, retired ashore.

Five years later the property changed hands, being bought by the fifth Baron Kensington. His father had died on a shooting trip the previous year, and the young William Edwardes (Eton and the Lifeguards) had come into his title and estates at the tender age of 28.

Kensington determined to focus his energies on his Pembrokeshire properties, and while his main interest was in developing Skomer as a shooting estate he was also interested in conserving his wild birds. The keepers he employed could serve both purposes.

Joshua Neale established good relations with him, both because he now controlled lawful access to the islands, for the Naturalists and others, and because he took the younger man’s commitment to conservation seriously.

Contempt

Neale had “considerable contempt for a number of the Pembroke gentlemen. I know their goings on and how they make trips time after time killing the birds and seals.”

As one of his colleagues told him, “The Society will never be forgiven by the aristocrats,” better described as the local gentry, for its role in the 1890 prosecutions, while “The fishermen fear you because you have shown that law can reach them all.”

But in Kensington he saw a potential ally. He cultivated similar relationships with other genuine aristocrats – the Earl of Cawdor at Stackpole, to protect the Elegug [guillemot] Stacks, and John W. Phillips (later Baron, then Viscount, St Davids), the local Liberal MP and proprietor of Ramsey, to look after the few remaining choughs.

By 1899 the Baron was planning to base a keeper on Grassholm for the summer, to repel visitors. Then disaster struck. William volunteered for service in the Boer War and was duly shot, dying in hospital weeks later.

Neale wrote to the Baron’s grieving mother to assure her that she could “at all times depend upon the Cardiff Naturalists Society assisting to protect the interesting birds of Pembrokeshire,” hoping that the family’s interest in conservation had not died with him.

Commitment

Fortunately her younger son Hugh, who became the sixth Baron at the age of 27, shared his mother’s and late brother’s commitment to “preserving the wild birds on the coast,” and when he returned from the war in 1902 as a live hero Neale acquired the patron he needed.

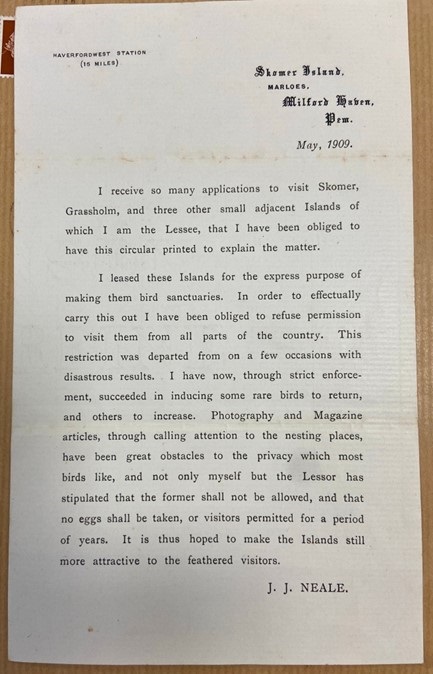

In 1904 the tenancy of the islands fell vacant, and in 1905 Neale took them on for ten years at £120 a year (£52,000 in current value, using the average wage method of indexing).

It was a most unusual tenancy agreement, a conservation lease obliging Neale not to allow any “pleasure parties” to land without Kensington’s prior written permission, nor to have any but his own family members, personal friends (i.e. the Society), and their servants staying with him.

No photographs were to be taken, except by members of the Neale or Kensington families – amateur wildlife photographers were becoming a new pest. He was to use “his utmost endeavours to preserve the sea birds and other wild birds frequenting the Islands and their eggs … to preserve the flora of the said islands and to protect and preserve the seals.”

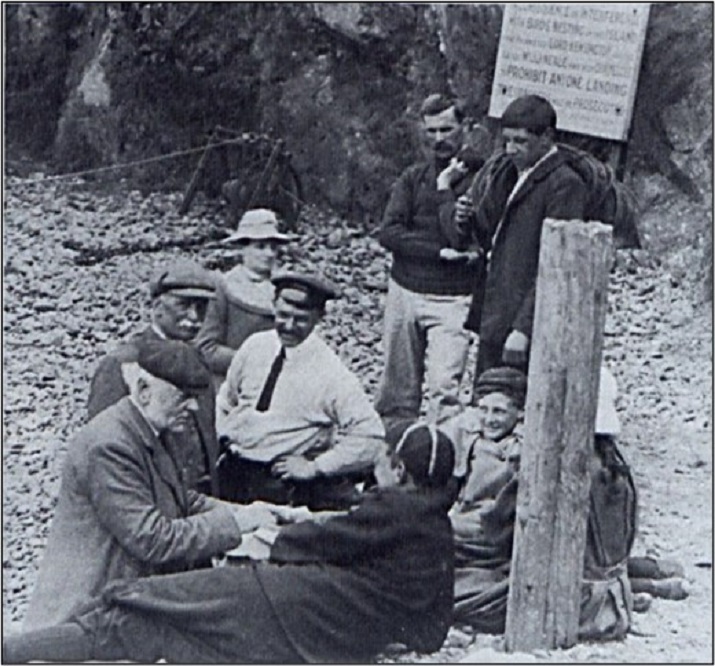

Neale swiftly appointed “watchers” to try to prevent people landing – implementing a strategy the RSPB had begun to adopt in other vulnerable breeding places – and the Naturalists made sure this was well known, reinforcing the message his notices provided.

Watchers

I do not know how effective the watchers were, or where they watched from. My guess is that Neale added watching Grassholm to the duties of his men on Skomer, which he also farmed.

But these limited measures achieved at least a qualified success: his son Stanley remembered that they “kept a keen watch on Grassholm to prevent any interference with the Gannets.”

So the small colony was not eliminated, like Lundy’s. It did not grow much, but neither did it collapse.

Brutal methods

Achieving this success also required the Naturalists to push back against the gannets’ worst natural enemy – the local fishermen – as well as tourists and egg collectors.

They were rivals for the same commercial species, and the local sea fisheries committee (which included my great-grandfather, whose sons were commercial trawlermen as well as marine salvors) called for gannets’ and other sea birds’ destruction as pests.

Fishermen also adopted their own DIY methods of reducing gannet numbers.

In addition to egg-raiding they had a simple but brutal method which provided a less effective but very satisfying form of revenge against their competitors: nailing a fish to a plank and floating it on the surface of the sea, so that gannets would kill themselves by diving into it.

This local contest was national news, just like (though not as much as) the larger drama of 1890, and once again the Naturalists won: no official cull took place.

And then Grassholm more or less disappeared from view in the national and local press for another twenty years, unless there was a shipwreck.

There was a big one in 1910, that of the S.S. Dalserf, a Cardiff collier, which caused weeks of disruption from marine salvors and visitors (the wreck turned into a tourist attraction) right through the breeding season from 10 July until at least September.

This cannot have helped the gannets’ chances of a successful year.

Splendid isolation

But that disturbance was followed by a long, critical period of splendid isolation .

The gannets’ main competitors for breeding space on the island, the colony of hundreds of thousands of puffins, had already collapsed well before the war, from destroying their own environment by burrowing and perhaps by epidemic disease too.

But gannet numbers did not increase until human pressures were also reduced.

Wartime limits on tourism and fishing had an enormously positive effect on the gannet population.

Liberated from casual as well as deliberate destruction, particularly thanks to the protective actions of German U-boats, which sank at least 39 vessels in the waters around Pembrokeshire between June 1915 and October 1918, Grassholm showed at last how many gannets the island and its surrounding waters were actually capable of supporting.

After the war, as Lord Kensington’s St Bride’s Castle estate began to be broken up, the islands changed ownership, but the new owner Walter Sturt, a retired dentist from Exeter, was also interested in looking after his wildlife and limiting the number of visitors.

He was not a very active conservator, but practised a sort of benign, unwelcoming neglect, focused more on Skomer, where he lived, than on Grassholm, where he could not police tourists and others so closely.

When the pioneer aviator Captain Vivian Hewitt – rich enough to fund his many hobbies and obsessions, which included egg collecting – visited Grassholm in his fast motor launch in May 1922, he found 800-1,000 breeding pairs, at least three times the prewar numbers.

Borderline illegal

Then two years later Cardiff Naturalists Morrey Salmon and Clemence Acland followed to carry out the first detailed photographic survey ever and, they thought, the first of any kind in a decade, until Hewitt corrected them after they had reported on their visit in Country Life and The Field.

His findings had been published in an egg collectors’ journal which only circulated among members of that no longer respectable, and borderline illegal, hobby, so when Salmon and Acland finally reached Grassholm after repeated weather delays they were quite unprepared for what they saw.

Acland reported that “When approaching Grassholm the air became filled with a whirling mass of birds very much resembling a heavy, but strictly local, snowstorm of very large flakes, confined to the south and west sides of the island.”

When she and Salmon climbed up and scrambled across the island to where they could see the gannetry that was the source of the “snowstorm,” they saw, in his words, “a rather astonishing sight”: not the few hundred birds prewar visitors had found, clinging to the edge of the island, but a sea of thousands –

the whole of one side of the island, and as far as the eye could see, were crowded together, in one vast concourse of snow-white birds, the huge gannet population, the nests placed so close together that in many cases they touched…; it was with difficulty that one could step over them.

Salmon’s photographer’s eye made even more of the scene:

Along the rocky slope, and extending as far as one could see towards the north, was a gleaming mass of gannets showing vividly white in the brilliant sun against the background of deep green sea and the black volcanic rock on which the nests were. Along the sloping cliff top they were fifty deep, nests as close together as possible, and on the rocks and cliffs every ledge was filled to its utmost capacity.

Horrible smell

The constant noise and the horrible smell “beggar[ed] description,” but the huge birds were very approachable, and did not object to close observation. It was an ornithologist’s heaven, a “truly wonderful island.”

They recorded 1,800-2,000 pairs, which, adding in non-breeding birds, suggests a total population of about 5,000 gannets – more than ten times prewar figures.

Grassholm had at last acquired what it would be known for from then on: not just the most southerly gannet colony in England and Wales, clinging onto its insufficiently protected rock, but celebrity as a natural marvel, with an enormously dense and growing population of big, charismatic birds that amazed subsequent visitors with its abundance.

With the arrival of Ronald Lockley on neighbouring Skokholm in 1927, the colony gained both a promoter and a protector. He served as a sort of self-appointed, unpaid “watcher,” doing his best to drive away egg-raiders as well as to save the gannets and other sea birds from other man-made hazards, from oil pollution to fires started by tourists.

Saturation point

By 1933, when Lockley and his friend Morrey Salmon did a more careful photographic survey than Salmon and Acland had managed in their hurried 1924 visit, there were c. 4,750 nests; by 1937, c. 5,000; by 1939, c. 5,750-6,000, and James Fisher concluded that Grassholm was getting close to its saturation point.

But by 1947, after the peace and quiet of another world war (except for one RAF practice bombing raid in August 1945), the total was estimated at 8,000 pairs, plus a couple of thousand more unpaired adult birds; by 1949, 9,200; and by 1956 the first aerial survey revealed 10,550 occupied nests.

Far from being saturated, the number of nests, and the amount of the island that they covered, just kept growing.

Grassholm now enjoyed the protection not simply of private proprietors but of Lockley and Julian Huxley’s West Wales Field Society and of the RSPB itself, which bought the island in 1947 and let the Field Society administer it. Ronald Lockley became their first Warden.

Accidental favour

The network of protections provided by them, the National Trust, the National Park, the Nature Conservancy, and successor bodies, has only grown with time. Oil pollution crises from frequent accidental spills and a couple of big tanker wrecks on Milford Haven, plastic pollution, and other dangers were dealt with or at least survived.

Grassholm became the third largest colony of northern gannets on Earth, with between 34 and 39,000 nests in 2009-2021.

So Grassholm turned from a site of wildlife crime in 1890, continuing for decades afterwards, into a conservation success story – at least until the recent avian flu disaster, which wiped out half a century of growth in a single year.

But it could quite easily have gone the way of Lundy, without the protective attention it received in the crucial quarter-century before the First World War.

Perhaps Colonel Saurin, Captain Haig, and their friends did the colony an entirely accidental favour when they landed on the island intent only on a bit of sport, and ended up in the dock.

The gannets of Grassholm will need even more luck, and continuing human protection, to recover from the latest threat to their survival.

Read the previous installments of the Gannets of Grassholm here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.