The Garden Pit Flood: Questions and consequences

Howell Harris

To expert contemporaries and later professional commentators, the cause of the Garden Pit Flood ‘accident’ was no mystery, and it was not a high spring tide that had not, in fact, happened.

Welsh-language newspapers were not afraid to attribute it immediately to negligence. The Carmarthen Journal evidently agreed. Choosing its words carefully, it demanded a “strict and searching examination” to discover why the catastrophe had occurred, and suggested that it might have been averted “if due diligence and skill had been observed on the part of the MINING AGENTS,” whose qualifications and experience could not be relied upon.

Matthias Dunn, b. 1788, a mining engineer from North-East England with decades of experience, including of earlier mass-fatality disasters caused by the inrush of water, saw Landshipping as a very familiar sort of calamity. The pit was an accident just waiting to happen. He did not visit in person, but as early as the 22nd of February obtained a detailed report, including a sketch of the workings, from a trusted and qualified local contact.

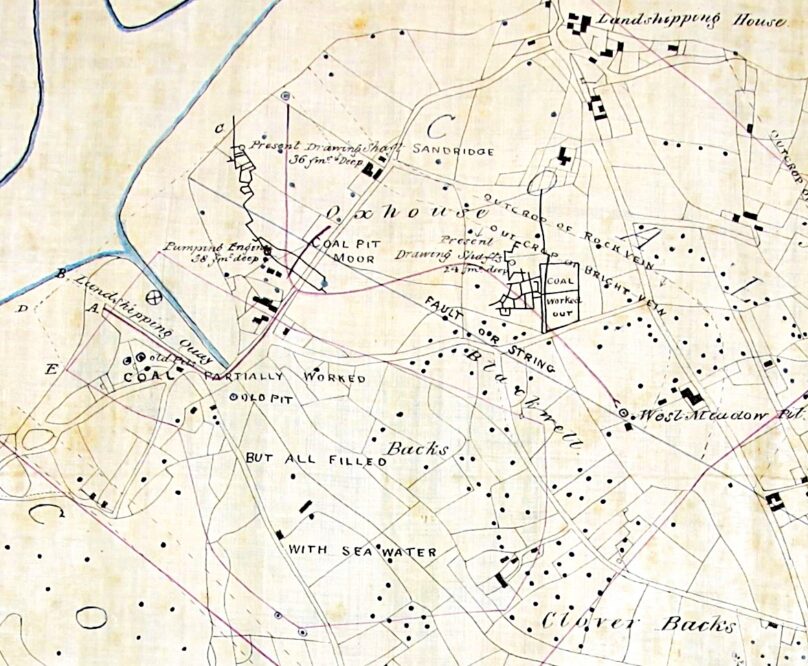

There were only three or four feet of rock over the Bright Vein, and above that just 40-60 feet of sand and mud. The decision to mine such a shallow seam with so little solid cover was “indiscreet” or even “most imprudent”; there had been ample warning, which is why the area had been abandoned for years, but “during a moment of thoughtlessness it was resumed, and the obvious consequences followed.”

Another mining engineer, Mark Fryar, lecturing at the Bristol School of Mines thirteen years later, was even more scathing: “Torpid ignorance is, in most instances, the cause of culpable neglect or reckless procedure” in ‘accidents’ like Landshipping’s.

Fifty years later, Landshipping remained an object lesson. The rather similar 1837 Workington disaster took place in an undersea mine where there was 90 feet of rock cover between the coal seam and the sea bed, and even that was not enough.

Landshipping’s 3-4 feet of solid roof were yet more grossly inadequate, which underlined the message that special care was required when mining beneath alluvium and loose sandy deposits, because it was hard to know how much dependable cover there really was.

There may have been 60 feet of cover on land, where the shaft was sunk, but beneath the muddy seabed of the Milford Haven, a drowned valley scoured out by glacial meltwater millennia ago? Landshipping’s miners knew how little solid cover they really had: they could tell by the salt water inflows that it wasn’t much, and claimed to be able to hear the oars of boats rowing above the shallow seam at high tide.

The modern understanding of the Landshipping disaster is that it was probably the result of a particular kind of structural failure: a “void migration”, where the roof of a mine collapses opening a growing void above it that usually ends up between 3 and 5 times, but sometimes as much as 10 or even 20 times, the original height of the collapsing tunnel.

At Landshipping the void did not have more than a fraction of that distance to travel before it broke through the thin rock cover and reached the muddy bed of the river, where it rapidly developed into what is known as a “crown hole,” the most dramatic form of ground collapse.

So when the predictable failure happened it flooded the mine with thousands of tons of water and mud within a few minutes. The timing of the roof collapse, with the mine full of workers, and its location, trapping most of them beyond any chance of escape, guaranteed that it would be a mass-fatality event.

What actually happened was therefore the reverse of the received version, still repeated even on the recent memorial plaque: far from the tide having broken through into the pit, the mine had actually broken through into the river. The result was the same, but the cause was not something conveniently inanimate, it was sustained human error compounded by sheer bad luck.

Why were most of the casualties not named?

There was another feature of the contemporary reports, apart from their glib explanation for the disaster and immediate conclusion that nobody was to blame, that helped feed later suspicions about a cover-up. The number of casualties given was accurate and consistent, but only the adult men were named. This was later interpreted as an attempt to conceal the presence of boys aged less than 10 in the mine and among the fatalities, and perhaps even of women too, which would also have been against the law.

There is a more innocent explanation, an effect of conventional early-Victorian standards: the lives of adult men leaving surviving dependents were valued enough to be worth naming; children, not so much.

The “sufferers” initially listed were just seven of the older men, with all the rest written off as “young men and boys.” By the following week more detail was provided, but it was still the (now) eight dead older men who took pride of place, listed with the number of their sons who died with them and the number of dependents they left behind, while two unmarried men were only worth an unadorned surname.

The other dead boys and young men did not even get that much individual recognition. Instead they were listed under their parents’ names, almost as if they were possessions of those to whom their death meant a reduction in household income as well as overwhelming grief. “Joseph Thomas lost one boy; James Owen one ditto; widow Davies two do.” So most of the dead did not even get an unabbreviated ditto to mark their passing, though each unintended insult only saved one bit of type.

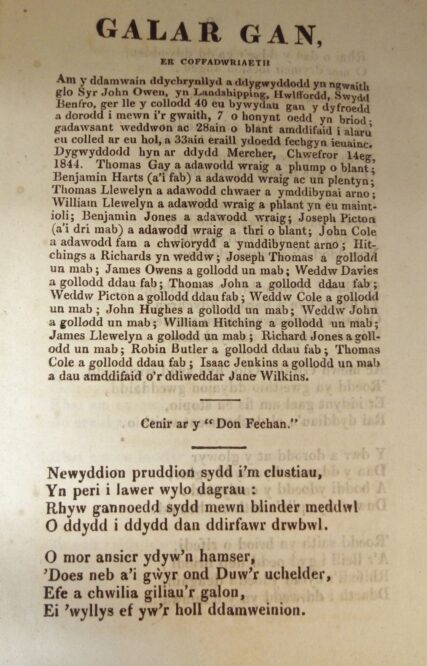

After the initial local reports, the flurry of reprints in the regional, national, and overseas press, and even the publication of a 23-stanza ballad (in Welsh), a Mourning Song (Galar Gan) to be declaimed to the music of a popular folk melody, the disaster disappeared from sight.

It had none of the essential ingredients of a newsworthy mining catastrophe, despite its size. There were no heartwarming stories of lucky escapes, no pithead vigils, no tantalizing reports of tapping from trapped miners heard underground by heroic rescuers who might or might not break through to them in time, no survivors brought back from the grave. Forty poor men and boys had died in an instant, and that was the end of it.

Even within the county there was far more reporting of the progress of the benevolent fund established to take care of dependents than there had been of the accident itself. It was quite an impressive effort. There were sermons and speeches, collections and subscriptions, Royal patronage, and in the end almost £400 was raised — £10 per victim, much better than the customary gift of a sovereign and a coffin to a dead miner’s grieving family.

What there was not was any investigation of the disaster. This, too, has raised suspicions among today’s local historians. Why is there no trace of any record of an inquest in the press, or the county or national archives?

Was it a matter of the Owens bringing their considerable local and even national influence to bear?

After all, they were both Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, men. Sir John was a long-serving MP, Lord Lieutenant, and “Custos Rotulorum” (principal Justice of the Peace and official keeper of the records), as well as the last holder of the grand but empty titles of Vice-Admiral of Pembrokeshire and Governor of Milford Haven. His son Hugh was Colonel commanding the local militia regiment, the Royal Pembroke Rifles, had been a local MP himself until 1838, and was still Deputy Lieutenant, an active JP (chairing the bench that had recently tried the Rebecca Rioters), and foreman of the county jurors at the Lent Assizes which met in Haverfordwest a month after the accident.

These suspicions seem reasonable, but the actual explanation for the absence of an inquest is so simple as to require no elite conspiracy to produce it. No bodies were ever recovered and, as the law then stood, no bodies meant no coroner’s inquest. In theory the Justices of the Peace had the power to act instead, but they rarely did. And neither the Landshipping nor the earlier and similar Workington pit inundation, another disaster with plenty of dead (27) but no bodies, stirred local JPs into action.

And even if there had been an official investigation, what would it have led to? Joshua Richardson, a contemporary mining engineer and safety campaigner like Matthias Dunn, was scathing about the inquest system. Verdicts “so very generally rather shield, than punish and expose, culpability.” The effects of fatal carelessness, ignorance, or avarice were routinely determined to be “accidental” deaths. Investigations were superficial, findings rarely reported, and no lessons were ever learned.

The Aftermath

The impact of the flooding of the Garden and Orielton pits on Landshipping’s output of top-quality anthracite for the London market was immediate, devastating, and lasting.

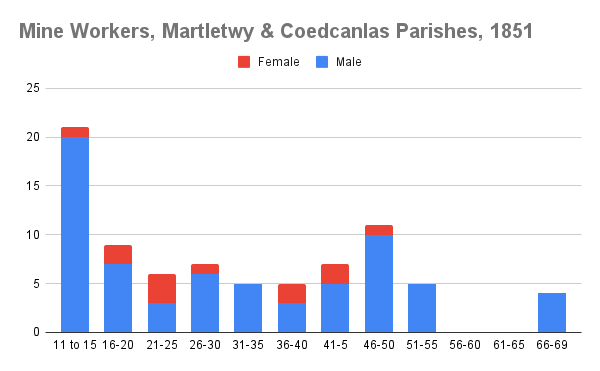

The Owens had other pits at Landshipping, and could compensate to some extent by working them harder to make up for the loss of some of their best coal reserves. They had only lost between a third and a half of their miners and helpers, and were quite successful at filling the resulting gaps.

Landshipping Estate Map, 1856, showing the underground flooding (but not its extension north-west under the Cleddau) and the location of the 1844 roof fall — the cross in a circle at the edge of the mud bank north-east of the Quay. The Garden was the “old pit” just south-west of the Quay. Pembrokeshire County Archives, DB-13-74.

Because so many of the dead had been so young they were easily replaced. So anthracite production bounced back, though it did not sustainably recover to previous levels; and the 1851 Census recorded more miners than 1841’s had, though this was partly because it was more complete, even including women.

When Herbert Mackworth, “the collier’s friend,” a civil and mining engineer and one of the first government Inspectors of Mines, visited Landshipping in 1853, he was not impressed by the results of the Owens’ stewardship of what they had left. Their shafts were shallow, winding gear and other machinery very “insecure”, and ventilation still grossly inadequate.

This was partly a reflection of the general backwardness of the Pembrokeshire mines, but also of a problem admitted in the auction advertisement for Landshipping in 1856, when the near-bankrupt Owens were finally forced to sell up. The mines’ output and efficiency had been “very much limited by want of capital.”

The Owens were too nearly broke to invest in their mines, because their priority was simply to squeeze them for cash as hard as they could. They only valued their clapped-out machinery and plant at £2,000, but in the five years to 1854 they had managed to bleed the mines of an average net profit (sale proceeds less expenses) of £2,200 per annum. “[J]udicious application of capital” could almost triple that figure, but the Owens lacked any such funds, even supposing that they could have managed to apply them judiciously.

They were in fact approaching the end of the road, and struggling to survive in business at all. The impact of the Garden Pit disaster on their mines’ output turned out to be the last nail in the coffin of their fortunes. As their debts mounted and other sources of income declined, the collieries became increasingly important to them, but however hard they squeezed, the short-term profit was not enough to tide them over.

It was not just Landshipping that they had to sell in 1856 but the entire Orielton estate, 11,700 acres at its peak, producing an income of £15,000 a year, but by the end just half that size, as well as their smaller, poorer Llanstinan estate (3,200 acres) in the north of the county.

Even this was not enough to clear their accumulated debts. By 1857 Colonel Hugh was back in Calais avoiding his creditors again; and when Sir John died in 1861, he left just £450 in personal effects.

In 1809 he had inherited a huge, unencumbered estate, a vast fortune of £135,000 (c. £160 million, relative to average wages then and now) securely invested in gilt-edged government bonds, and other funds too. One way and another he had managed to blow it all, including £12,000 (most of Colonel Hugh’s only independent wealth, from his first wife’s marriage settlement) that he had borrowed in 1832 and never repaid.

His grandson, also a Sir Hugh, thought that his grandfather “was a man of conspicuous ability, and would have attained a high position in his profession [barrister] if he had not had the misfortune to inherit Orielton.” It was a misfortune that he managed to share widely.

Astonishingly, Hugh Owen Owen (now a Sir rather than just a Colonel) managed to bounce back. As his eldest son recalled after his death, he “inherited his father’s title and his popularity, but little else.”

Even though all he had left was the land settled on his second wife and their children — his beloved first wife died suddenly a few months after the Garden Pit catastrophe — and the family property in Tasmania, “[b]y recourse to chancery proceedings, interdependent conveyances, mortgages, remortgages and life insurance policies, he was able to clear his debts” by the time of his father’s death.

This enabled him to run for his and more recently his father’s old Pembroke Boroughs seat, now as a Liberal with Radical support rather than a Tory. He succeeded at his second attempt, and had two more terms in Parliament. He was, even his opponents agreed, “one of the finest and best-hearted gentlemen in the county, almost universally beloved, and ready to hold out the right hand of friendship to his opponents.”

Even after he lost his seat in 1868, his public life was not over. He remained a Justice of the Peace, Colonel of what was now the Royal Pembroke Artillery until succeeded by one of his sons in 1875, and even became an Aide de Camp to Queen Victoria, a rank he held from 1872 until 1889, when he retired because of his failing health.

He was much poorer than he had been — in 1873 he only reported owning 286 acres of land in Britain, producing just £20 of gross rent per year, and gave his address as his London club. But he was poor only in the way that the once rich, with good professional advisors and still-rich, helpful relatives and friends, can be. His sons pursued very respectable careers, his daughters married well.

He died in 1891, aged 87. His obituary in the local press memorialised him as “accomplished, courteous and genial” and “in all respects a gentleman,” painting an attractive, affectionate picture. His role in the largest mining disaster in Pembrokeshire’s history was quite forgotten.

Public record

It is easy to outline the lives of Sir John Owen and his son after the Garden Pit disaster. But its impact on those it affected most — the eighteen survivors, most of them boys, and the relatives of the forty dead — has left no similar trace in the public record.

All that one can say with confidence is that, as the Landshipping mines began their decline under the Owens, which continued under their successors, people started to leave a community offering ever-fewer jobs, however wretched, and seek opportunity or at least a living elsewhere.

A semi-industrial parish turned within decades into what we see nowadays — a depopulated, once again beautiful rural backwater with hardly any visible relics of its mining past except for its dispersed settlement pattern, and ripe for inclusion within the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park from its creation in 1951. There is still a house on the site of the old Garden Pit, and bearing its name. Today it is a dog-friendly holiday retreat.

The Wider Impact

In one respect the Garden Pit disaster did have a lasting, national effect. When the House of Lords established a Special Committee in 1849 to “inquire into the best Means of preventing the occurrence of Dangerous Accidents in COAL MINES, and to report to the House,” one of its key witnesses was Matthias Dunn, vastly experienced and widely respected. Oliver MacDonagh, historian of the first decade of coal mine safety legislation in Britain, called him “the most interesting reformist.”

The Committee’s focus was on reducing the explosion risk via improved ventilation and other measures, but Dunn made sure that they were aware of another, even more neglected source of danger: flooding. Through him, the Heaton Main, Workington, and Landshipping disasters made their way into the Committee’s report and recommendations.

There is one other cause of fearful catastrophes which must not be left unnoticed, though of more rare occurrence, that of inundations. These arise in all cases from a dangerous approach of the workings to some body of water, such as the sea, or frequently that collected in old and abandoned excavations. There can be no remedy for these but caution where the danger is known, and a correct record of workings, to secure that knowledge.

It was not much, but it was at least something. Proposed remedies were a requirement on mine owners to create and preserve accurate mine maps, and, Dunn’s favourite, regular independent inspection to identify hazards and encourage the improvement of mine owners’ and managers’ professional practice.

The resulting 1850 Act embodied both of these recommendations, and though these and other new regulations were rudimentary, they were at least a beginning on the long road to reducing the industry’s toll of death and injury. Matthias Dunn was one of the first Her Majesty’s Inspectors appointed; Herbert Mackworth, whose critical view of the Landshipping pits’ standards in 1853 was noted above, another. They investigated, they gave evidence to and otherwise participated in inquests to try to improve their quality and value, and they made endless recommendations for improvement.

It would be impossible to argue that the Garden Pit disaster made a major contribution to the arguments about the necessity of reducing the dangers in coal mining and the best means of addressing the task. But it was definitely there in the mix. The completely avoidable deaths of forty men and boys were not entirely forgotten, or without any positive legacy.

And, once the inspectors had been appointed, and started their regular annual reporting, including detailed tables of every “accidental” death and its causes, victims of future Garden Pits would at least have the small satisfaction of having their names inscribed somewhere. David Llewhelling, 29, the last miner recorded to have died on Colonel Hugh Owen’s watch, in April 1856 (he fell down a shaft), was an unlucky beneficiary of this new dispensation. He had probably survived the Garden Pit disaster, when his younger brother William died without even having his name recorded. This second time David was a little more, as well as a lot less, fortunate.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

A good read…hard rock round here and just the one below the river, but the thought must have been present…

Remarkable essay. Demonstrating how easy it was, is, to identify the causation of such tragedies was the callous exploitation of working people. It’s different today of course. It’s not so easy to link the deadly results of the greed, & contempt of the moneyed classes. But capitalism still wrecks & prematurely takes young lives in the cause of pleonexia. It’s why I’m a Marxist. I believe it’s why all Welsh people should be!,