The hidden history of Wales’ child miners

Amgueddfa Cymru

When the Royal Commission Report on the Employment of Women and Children in Mines was published in 1842, it sent shockwaves through Victorian Britain.

Led by Lord Ashley, the inquiry exposed in harrowing detail the reality of life underground for thousands of children – some barely five or six years old – and for the women who worked beside them.

Its pages were filled with graphic testimonies and stark illustrations.

The public outcry was immediate. The idea that children were labouring in narrow seams, dragging heavy drams on hands and knees through stifling tunnels, or spending long days alone in pitch-black passages guarding ventilation doors, appalled a nation that had largely been unaware of the conditions they worked under

That wave of anger and moral reckoning forced Parliament to act.

The result was the Mines and Collieries Act of 1842 – the first legislation to ban women and boys under ten from working underground.

Asleep

Mary Davis was a ‘pretty little girl’ of six years old. The Government Inspector found her fast asleep against a large stone underground in the Plymouth Mines, Merthyr.

After being wakened she said: “I went to sleep because my lamp had gone out for want of oil. I was frightened for someone had stolen my bread and cheese. I think it was the rats.”

Susan Reece, also six years of age and a door keeper in the same colliery said: “I have been below six or eight months and I don’t like it much. I come here at six in the morning and leave at six at night. When my lamp goes out, or I am hungry, I run home. I haven’t been hurt yet.”

A coal mine was a dangerous place for adults, so it is no surprise that many children were badly injured underground.

“Nearly a year ago there was an accident and most of us were burned. I was carried home by a man. It hurt very much because the skin was burnt off my face. I couldn’t work for six months.”

Phillip Phillips, aged 9, Plymouth Mines, Merthyr

“I got my head crushed a short time since by a piece of roof falling…”

William Skidmore, aged 8, Buttery Hatch Colliery, Mynydd Islwyn

“…got my legs crushed some time since, which threw me off work some weeks.”

John Reece, aged 14, Hengoed Colliery

Child Colliers and Horse Drivers

Some children spent up to twelve hours on their own. However, Susan Reece’s brother, John, worked alongside his father on the coalface.

“I help my father and I have been working here for twelve months. I carry his tools for him and fill the drams with the coal he has cut or blasted down. I went to school for a few days and learned my a.b.c.” John Reece, aged 8, Plymouth Mines, Merthyr

Philip Davies had a horse for company. He was pale and undernourished in appearance. His clothing was worn and ragged. He could not read.

“I have been driving horses since I was seven but for one year before that I looked after an air door. I would like to go to school but I am too tired as I work for twelve hours.” Philip Davies, aged 10, Dinas Colliery, Rhondda

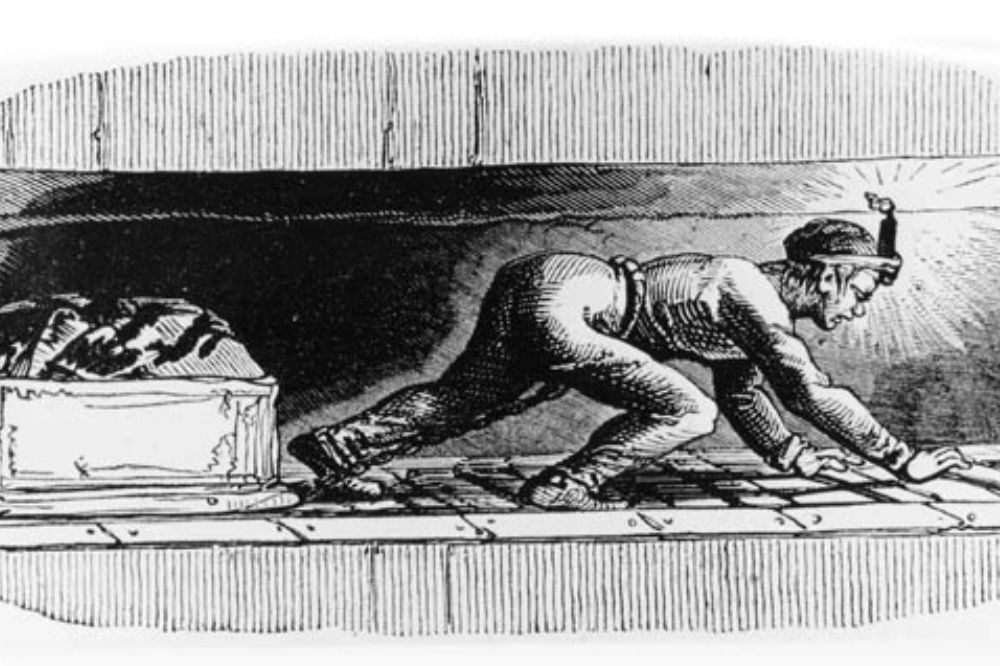

Drammers pulled their carts by a chain attached at their waist. They worked in the low tunnels between the coalfaces and the higher main roadways where horses might be used.

The carts weighed about 1½cwt. of coal and had to be dragged a distance of about 50 yards in a height of about 3 feet.

“My employment is to cart coals from the head to the main road; the distance is 60 yards; there are no wheels to the carts; I push them before me; sometimes I drag them, as the cart sometimes is pulled on us, and we get crushed often.”

Edward Edwards, aged 9, Yskyn Colliery, Briton Ferry

For this a drammer would earn about 5p a day.

Three Sisters

The Dowlais iron works also owned iron and coal mines; they were the largest in the world at this time and supplied products to many parts of the world. However, they still relied on children for their profits.

Three sisters worked in one of their coal mines.

“We are doorkeepers in the four-foot level. We leave the house before six each morning and are in the level until seven o’clock and sometimes later. We get 2p a day and our light costs us 2½p a week. Rachel was in a day school and she can read a little. She was run over by a dram a while ago and was home ill a long time, but she has got over it.”

Elizabeth Williams, aged 10 and Mary and Rachel Enoch, 11 and 12 respectively, Dowlais Pits, Merthyr

After the Act

The publication of the Report and the ensuing public outcry made legislation inevitable. The Coal Mines Regulation Act was finally passed on 4 August 1842.

From 1 March 1843 it became illegal for women or any child under the age of ten to work underground in Britain.

There was no compensation for those made unemployed which caused much hardship. However, evasion of the Act was easy – there was only one inspector to cover the whole of Britain and he had to give prior notice before visiting collieries.

Therefore many women probably carried on working illegally for several years, their presence only being revealed when they were killed or injured.

The concept of women as wage earners became less acceptable in the mining industry as the years went by.

However, a small number of female surface workers could be found in Wales well into the twentieth century.

In 1990 the protective legacy was repealed and after 150 years women are once again able to work underground.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Presumably Reform plan to solve child poverty and deregulate to grow the economy by abolishing the Coal Mines Regulation Act.