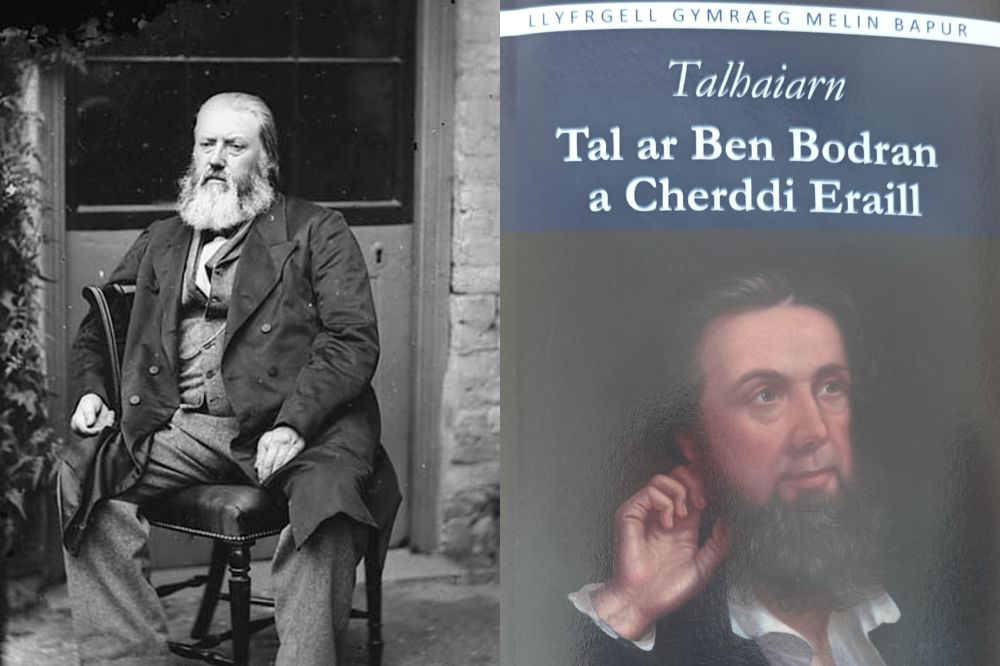

The Lyrical Bohemian: The poetry of Talhaiarn

Adam Pearce, Editor, Llyfrau Melin Bapur Books

It’s an interesting fact about Welsh poetry in the nineteenth century that so many of its most fascinating practitioners, and those who produced the work of the most lasting value, were outside the mainstream.

Whilst some, like Eben Fardd, were highly thought of by both contemporaries and later critics, many of the period’s best loved figures laboured in obscurity (Ann Griffiths and Islwyn) whilst others (like RJ Derfel) deliberately turned their back on established aesthetic standards, or rebelled and sought to overthrow them (John Morris-Jones). Meanwhile, there is a long list of multiple-chair-and-crown winning figures celebrated in their time and yet now long forgotten.

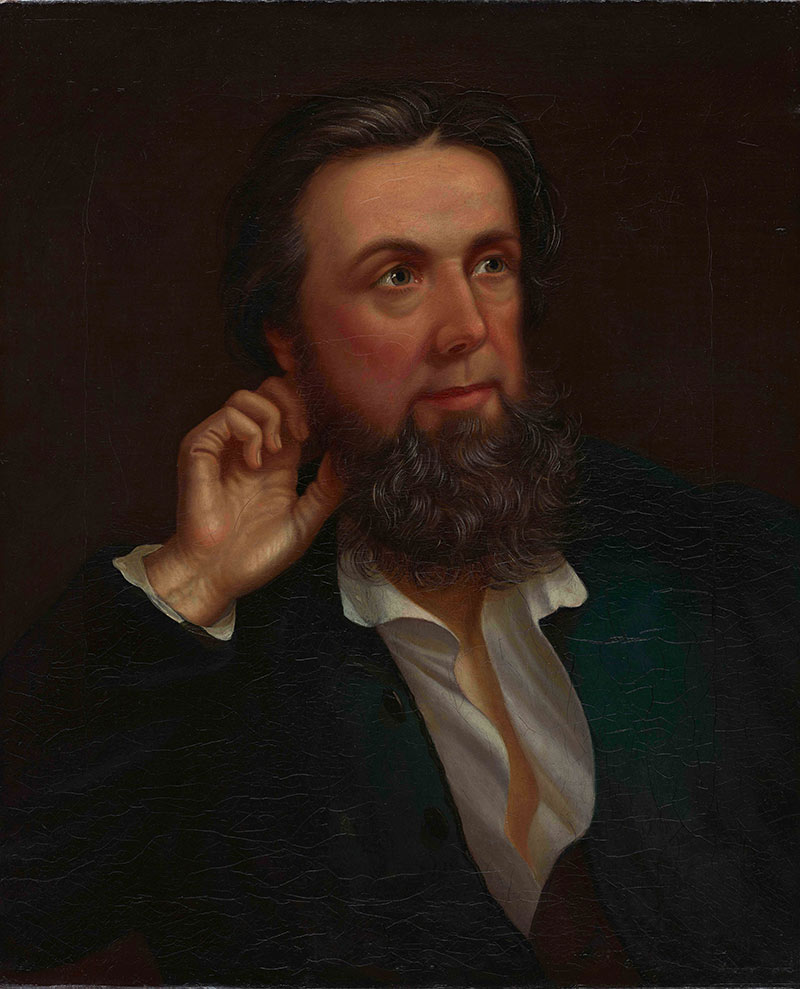

The life ambition of the subject of the latest volume in Melin Bapur’s ongoing Llyfrgell Gymraeg (Welsh Library) was to win an Eisteddfod chair; but though a popular poet Eisteddfodic glory would elude him. Nevertheless to critics and readers he is one of the very finest and most immediately accessible of Welsh poets of his age, and to the uninitiated is perhaps as good an entry-point as any into the poetry of this period. He was also a fascinating character who broke the mould of what was expected of a Welsh poet in every sense (which almost certainly contributed to his competitive failure), but in a way that makes him an endearing character today.

One could get a surprisingly good overview of Welsh literature just by studying men named John Jones. This particular one (1810-1869) was born in the Harp Inn in Llanfair Talhaearn (in what is now Conwy County Borough, but historically a part of Denbighshire), the village from which he took his bardic name, Talhaiarn (the spelling with an ‘i’ was his own insistance).

By the early nineteenth century much of Wales’s folk culture was in serious decline – retreating not in the face of English, which had made barely any inroad yet in most of the country, but the increasing dominance of the Welsh Nonconformist chapels. One of its last bastions was in fact pubs like the Harp.

Though somewhat out of the way these days since the building of the A5 and A55, at the time Llanfair would have been on one of the main drover routes between rural Wales and the major markets in England, and the pub was a busy place where the young Talhaiarn would have been surrounded by balladeers, folk singing, harp playing (and no doubt other rather less wholesome pursuits). It was this background and folk culture that gave Talhaiarn such a love for song and poetry, as well as beer and merriment.

It was his mother who ran the pub, whilst his father worked as a carpenter; this double income meant the family were comparatively well off for the time. This meant they were able to apprentice their son to an architect, with whom he would work on some of the grandest buildings in north-east Wales, not least among them Gwrych Castle, near Abergele.

He maintained his love of poetry and song, however, and began turning in local literary circles and publishing his work in print. He leapt at an opportunity to move to London and work for a firm restoring churches in 1843, and joined the influential ranks of the London Welsh society of Cymreigyddion.

By this point he was becoming increasingly well known as an expert on Welsh culture, especially its folk culture and songs; he was also regularly publishing poetry. He was also, however, becoming known as a participant in raucous drinking sessions and wild parties in the city’s rougher quarters.

Distinctiveness

As befits a character of unlike the typical Welsh poet of his age, Talhaiarn’s poetry has a number of features that make it quite distinct from that of his contemporaries. Although Welsh folk culture the most obvious influence, also prominent was the work of romantic poets from the rest of Britain, like Byron and Robert Burns, of whom Talhaiarn produced several translations into Welsh, unusual at the time – his translation of Burns’s Tam O’Shanter is a real highlight of his earlier work. It is striking and almost unique at the time that there is almost nothing overtly religious in Talhaiarn’s poetry, which deals almost entirely with love: his love of women, of his country, but also for drink and merriment.

The poetry for which he was best known in his own day was that which he composed to be sung. Talhaiarn would write words the words for new settings of traditional Welsh melodies, to be sold as collections which proved exceptionally popular. Name a Welsh folk melody, and there’s a very good chance Talahaiarn wrote some words for it – Ar Hyd y Nos, Men of Harlech, Dafydd y Garreg Wen, The Ash Grove, Morfa Rhuddlan – and though Talhaiarn’s are rarely the best known versions (perhaps because he was often setting tunes that were already popular) they are none the worse for that. One, Mae Gen i Dŷ Cysurus, even showed up on Dafydd Iwan’s album for children, Cwm Rhyd y Rhosyn!

He also wrote songs which were set to original music, with one in particular, Mae Robyn yn Swil, becoming one of the most popular Welsh songs of the nineteenth century.

There was a certain facile easiness to much of this work though, and critic Bobi Jones went so far as to contemn him for writing “miles of tasteless lyrics”. He can perhaps be forgiven for taking advantage of the few ways in which a Welsh poet could monetise their talent at the time.

Although his songs had brought him fame and popularity, like most Welsh poets his great ambition was to win an Eisteddfod chair. His first attempt, at Aberffraw in 1849, provides one of the strangest and most awkward anecdotes in Eisteddfod history. Certain of victory, Talhaiarn spared no expense in binding his awdl on Y Greadigaeth (the Creation) in Moroccan leather, with gold lettering and illustrations.

When – inevitably – his poem was torn to shreds (figuratively) by adjudicator Eben Fardd, Talahairn, enraged, tore his poem to shreds (literally). There are contradictory reports as to exactly where this happened (on the stage in front of the audience, some claim, whilst others suggest he stormed off). Whatever exactly happened it was clearly indecorous enough to warrant publishing a public apology for his behaviour in the press a few days later, and – as befitted a poet – a cywydd apologising to Eben Fardd. The two would become friends, exchanging letters until the older poet’s death in 1863.

Talhaiarn found more success in his day job, entering the employment as a “clerk of works” under architect Joseph Paxton, with whom worked on some of the grandest and most magnificent buildings in Victorian Europe: Mentmore Towers in Buckinghamshire and Château de Ferrières near Paris, both homes belonging to the ultra-wealthy Rothschild dynasty, as well as London’s Crystal Palace.

Enduring works

His years of exile did not prevent him maintaining his public profile in the press, and in 1852 the first parts of his largest work, Tal ar Ben Bodran, began to appear. A sprawling work, difficult to categorise, it took ten years to finish; it describes a series of conversations between Talhaiarn and his muse on the hilltop overlooking his hometown. Though their conversations range widely and much of the material is slight, the poem (if it can be called such, as there are long prose passages) also contains some striking passages describing the poet’s nihilistic depression, with his muse vainly trying to cheer or distract him from his melancholy.

This intensely bleak material, concentrated in the last two of the poem’s twenty ‘cantos’ but present throughout, is unlike anything else written in Welsh, and led Saunders Lewis to describe it as one of the great Welsh works of the nineteenth century. Although the work as a whole is perhaps too meandering and uneven to call a masterpiece, its peaks are undoubtedly moving and evidence of a unique and individual talent. As a self-contained work the final canto represents a meditation on melancholy and hopelessness unmatched in Welsh literature.

Further attempts at Eisteddfodic success proved as fruitless as the first, and Talhaiarn would frequently compound things by complaining of mistreatment and that the nonconformist poetical establishment was prejudiced against him. These complaints were not entirely unjustified: at the 1863 National Eisteddfod the adjudicators failed to follow the competition’s rules in a way that prevented Talhaiarn winning, though it is not clear that this was necessarily indented.

It seems to me however that Talhaiarn’s failure at the Eisteddfod was due mainly to the fact his muse did not lend itself to long, serious poetry of the sort that won chairs. The introspective, nihilistic passages of Tal ar Ben Bodran excepted, Talhaiarn’s finest works are on a smaller canvas: not so much his songs, but in shorter poems like his lyric to Caerffili, which is the equal of many more celebrated works by others in a similar vein:

Yn lle y seirian arfau dur,

A gwridog wedd y cedyrn wŷr,

Ymhob ystafell, cell, a mur,

Adfeiliant sy’n bodoli:

Nid oes yn awr na gwin na medd,

Na rhyfyg afiaith yn y wledd,

Ond distaw, fel y distaw fedd,

Yw Castell mawr Caerffili.

[Instead of glittering steel blades

And the flushed faces of sturdy men

In every room and cell and wall

One finds only ruin;

Gone now the wine and mead

The proud mirth of feasts:

Silent, like the silent grave

The great castle at Caerphilly.]

Talhaiarn was also a witty satirist, an area in which his irreverence for once was an advantage, as in this extract from his poem satirising the Eisteddfod:

Yr oedd y Babell fawr

Yn orlawn o wladgarwyr,

A rhai o’r rhain yn awr

Yn fwy eu sŵn na’u synnwyr:

Roedd yno rolyn gwag

llai o wit na bloneg,

Yn brolio’r iaith Gymraeg

Mewn araith hir yn Saesneg.

Roedd corau mawr eu sŵn

Yn canu am y gorau,

Yn gwneud wynebau cŵn

Wrth brofi nerth eu lleisiau:

Roedd rhai o lid yn llawn,

Wrth wrando ar y Beirniad,

Yn barnu’n groes i iawn:

Felly y bydd hi’n wastad.

[The great Pavilion

Was brimming with patriots,

Some of whom now

More full of bluster than sense:

There was one empty roll

With less of wit than blubber

Praising the Welsh language

In a lengthy tract in English.

The great and noisy choirs

Were singing in competition

Making faces like dogs

To show the strenght of their voices:

Some filled up with rage

When listening to the judges,

Juding incorrectly:

As it always is.]

A darker side

Another satirical poem, Dic Siôn Dafydd yr Ail, plays with the Dic Siôn Dafydd stereotype by inverting it: returning home from England, Dic Siôn Dafydd II retains his language and identity, but earns the scorn of his countrymen anyway for failing to achieve worldly success.

For all this playful humour, mirth and cheer, the lasting impression of Talhaiarn’s poetry however is of darkness and melancholy, and although to a certain extent this was probably playing up to contemporary cliches of the lonely Romantic poet it’s clear that Talhaiarn really was a rather lonely and troubled figure. He never married, and suffered terribly from gout, particularly towards the end of his life: his letters also seem to hint at another affliction arising from his past excesses, perhaps some kind of venereal disease. He returned to the Harp and although many sources claim his death there in 1869 was a suicide, his biographer Dewi Lloyd revealed that this desperate attempt with a pistol unsuccessful, but that he died of his illness a few days later regardless.

Talhaiarn’s reputation declined somewhat after his death. He tended to be grouped with younger lyrical poets like Mynyddog and Ceiriog who wrote in a similar lyrical vein but whom prudish late Victorian audiences found more to their tastes; Talhaiarn’s irreverence and avoidance of religious subjects did him no favours in a culture for which seriousness meant piety.

Later poets were better able to appreciate him: he was a significant influence on the young John Morris-Jones for example, who links him in turn to the major poets of the twentieth century like W. J. Gruffydd, T. Gwynn Jones and R. Williams-Parry. He represents the link between these celebrated figures and the older lyrical tradition of poets like Alun as well as the folk balladeers and songsters of the eighteenth century and earlier.

Modern readers are likely to appreciate Talhaiarn for exactly the same reasons Morris-Jones did: they will find in Talhaiarn’s work a willingness to explore some of the darker aspects of human nature that is more ‘serious’ than the bland piousness of many Victorians, combined with a lyricism that is every bit as appealing and accessible as more celebrated later poets. Our new volume of his poetry contains Tal ar Ben Bodran in its entirety, for the first time, as well as a representative sample of his popular songs, whilst focusing on his satirical poems and his more serious lyrics.

Talhaiarn’s Tal ar Ben Bodran a Cherddi Eraill is available now from www.melinbapur.cymru and all good Welsh bookshops for (£11.99+P&P). Also released from Melin Bapur this week is a new edition of T. Rowland Hughes’s classic novel William Jones (£12.99+P&P).

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Da iawn. Gweler hefyd Hen Lyfr Bach Cerddi Talhaiarn (Dalen Newydd, 2023), £5.00. Ac i wneud y drindod, Hen Lyfr Bach Caneuon Mynyddog (2016), £3.00, a Hen Lyfr Bach Ceiriog: Alun Mabon a Cherddi Eraill (2020), £5.00. Oll ar gael o dalennewydd.cymru