The Misses Santa Claus

Norena Shopland

Ettie Carr was born into a life of luxury, the daughter of Henry Lascelles Carr a British newspaper proprietor whose titles included the Western Mail, Evening Express, and News of the World.

While still at school in Monmouth, Ettie was moved by the plight of poor children and persuaded her father to let her hold a ‘feast’ for them in Cardiff. The first taking place in 1893, for 1,000 children up to the age of twelve, but just a few years later demand was so high it had been split into two days for 1,000 girls and the same for boys.

Preparations had begun months earlier when Ettie and her committee published appeals for money and donations in her father’s newspapers.

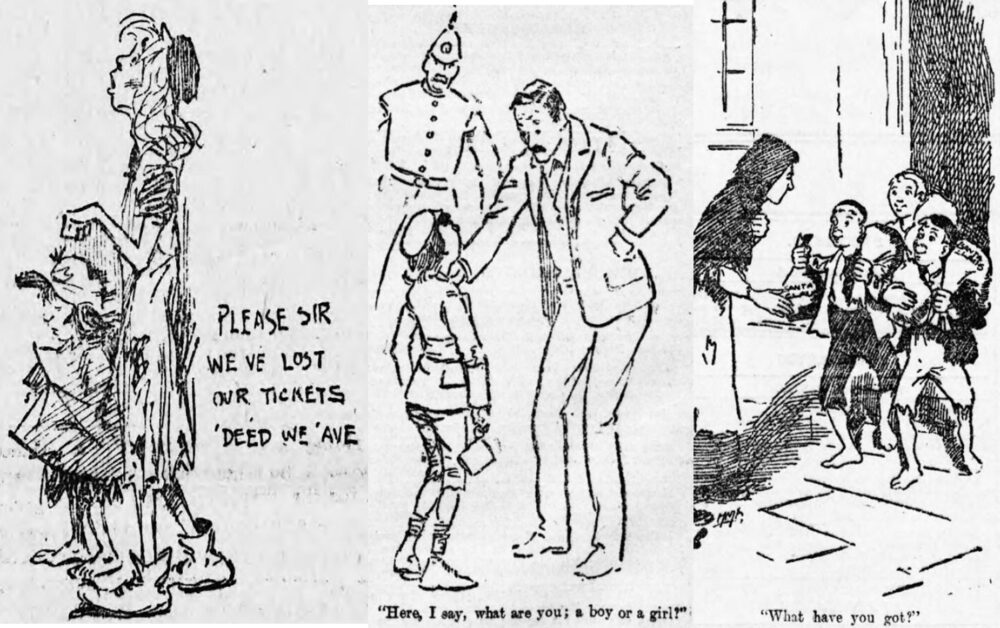

Each year they raised around £200 (about £30,000 today) and received around 500 bags of clothing and gifts. Nearer the time, tickets were sent to religious leaders and charity workers to hand out, but only those within a narrow selection process.

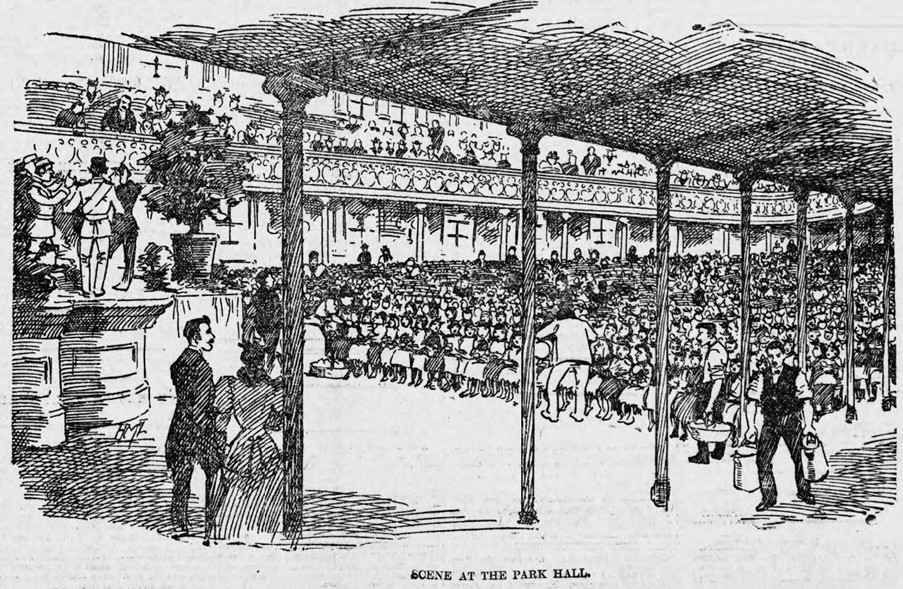

Hundreds of children, often walking long distances arrived at Park Hall to be greeted and presented with a tin tankard stamped with ‘Evening Express Santa Claus’ and the date.

Once seated, they were given a large paper bag including cakes, pies, oranges, nuts and sweets.

The hall was brightly coloured, had a large Christmas tree, and a pianist playing popular songs.

One journalist, commented on how such young children could know the lyrics of popular songs, to be told by an attendant clergyman that ‘in some way or another they do manager to get into the Empire, and that frequently.’

Sceptical that a clergyman would attend the Empire, and annoyed by his discrimination the journalist chose to believe that the children had probably learnt the songs from family and friends.

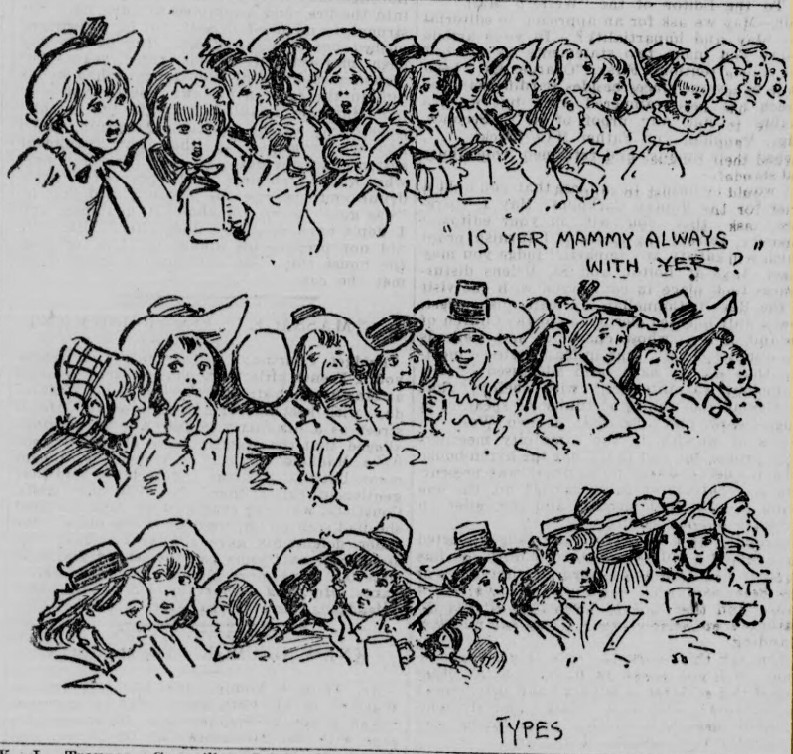

Several journalists attended, and wrote of the ‘dear little creatures’ huddled together in their rags. Some detractors, complaining the children seemed reasonably well dressed for being poor, were quickly put in their place. Explaining that parents had scrupulously cleaned clothes and borrowed from everyone they knew.

One young girl’s cloak belonged to a friend, the hat was her elder sister’s and the boots were her brother’s.

One mother had sat up all night sewing her daughter’s clothes to make her look presentable. One was the third child of ten, another one of seven, neither had fathers and their mothers took in ironing and washing.

‘And their hats!’ exclaimed one journalist, ‘They presented quite a study in headgear. Some wore hats of straw, trimmed with a little ribbon, and some with broken crowns; here and there was one with a bonnet and anon a girl with only a shawl thrown over her head.’

Many of them, ‘were in garments that might mislead one as to the sex of the wearers.’ One boy had used his sister’s ticket as she had been too ill to attend, and he had not received his own ticket for the boy’s event.

Little John, turned out to be Cissie who, her brother explained had been too young to be on her own for the girl’s day. They were both allowed to stay.

There was little diversity. Occasionally a blind, deaf or crippled child was mentioned. An 1897 journalist wrote, ‘This Cardiff is a curious place. It seems like a cauldron of the gods, where several races are finely mixed together.’ At least the white races, there is little mention or imagery of ethnic diversity with an exception from 1897 that ‘a few (half-castes) were nearly black, and others were ruddy.’

The galleries overlooking the Hall were full of ‘well-to-do inhabitants of Cardiff,’ and tickets were hard to get. Making it uncomfortably close in nature to those who wandered around Bedlam gawking at the insane patients.

Everywhere was Ettie, ‘Miss Santa Claus,’ making sure everything ran smoothly. When she married in 1898 her sister, Jennie took over and, on her marriage, it was run by the third sister, Mattie.

After three hours, the one day of the year when children ‘forgot to shiver… forgetting the squalor of their lives,’ they left. Exiting, they received sacks of clothing, toys and three pennies.

Outside parents were waiting, some women shivering in rags in the cold. One young boy introduced a lady journalist to his mother, ‘Oh! such a sad, wan, weary, hungry-looking woman! She looked far more in need of food than her rosy little boy. The old story her’s of a drunken husband out of work, and she denying herself for her brood.’ The boy had saved his pork pie for her.

Not all children were included. As soon as the publicity began, the newspaper offices were besieged by parents or ‘half-starved and ill-clad’ children begging for tickets.

Hundreds had to be turned away. One clergyman wrote to Ettie saying she had sent him thirty tickets but he had received 1,000 applications. Mothers were crying and going down on their knees to him begging and next year, he wrote, he would refuse any tickets because he could not go through that again.

By the end of the 1890s, it was becoming too expensive to host, although various ‘feasts’ did continue.

Nevertheless, several years coverage of Ettie’s events allows us some images of working-class children that otherwise would not have been available.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.