The Tragic Exile – the poetry of Gwenffrwd (1810-1834)

Adam Pearce, Llyfrau Melin Bapur

There’s something compelling about an artist who dies young. Schubert, Keats, Hedd Wyn, Buddy Holly, Jimi Hendrix – the tragedy of being taken from us so soon adds a layer of pathos to their work, as well as inviting the inevitable and understandable speculation about what might have been, had they only lived.

When it comes to Welsh literature, soldier-poet Hedd Wyn, who died on the Western Front in the First World War, is perhaps the first name that springs to mind when we think of those cut down before their time, but almost a century earlier another Welsh poet who died young provided the fledgling Romantic movement in Wales with a tale of genius cut tragically short. Though perhaps not so well known today, he was widely recognised as a genius by his contemporaries who believed that in his early death, aged just twenty-three, Wales had lost its most promising young son.

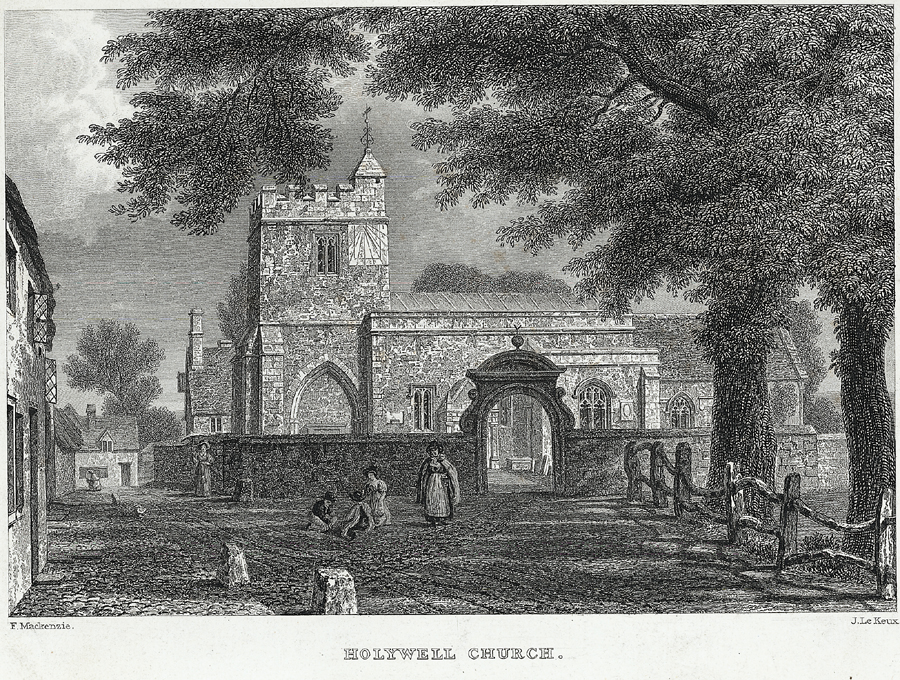

Thomas Lloyd Jones, or Gwenffrwd, to use his bardic name, was born in or near Holywell, Flintshire in 1810. Not much is known definitively about his early life, nor indeed are many of the details of his brief adulthood, and no known picture of him has survived. The accounts of his early years are in broad agreement that his family were poor, which makes it unlikely he would have received any formal education. As a teenager he worked in one of the town’s cotton mills, but by eighteen he was employed as a clerk to a lawyer, and he must naturally have been literate.

It is not known who taught Gwenffrwd to write poetry – a possible candidate is Alun (John Blackwell), thirteen years his senior and curate in the Parish Church at Holywell whilst Gwenffrwd was still living there, though there is no formal proof that the two ever met except at the Beaumaris Eisteddfod of 1832. Regardless, aged just 18 he was already writing poetry, and translating the work of various fashionable English poets into Welsh.

By 20 years old, Gwenffrwd achieved the remarkable feat of compiling and editing an anthology of Welsh literature, Ceinion Awen y Cymmry [sic]; ‘The Beauties of the Welsh Muse’. This was in fact one of the very earliest printed anthologies of Welsh literature to be explicitly intended, and marketed, at ordinary people, and would, in its time, have been the cheapest available such work. The work features poetry as early as the ninth-century Canu Heledd as well as much later works, and heavily features work by Gwenffrwd’s own contemporaries such as Alun (1797-1840) and Ieuan Glan Geirionydd (1795-1855), and also the notorious pseudo-grammarian William Owen Pughe (1759–1835), who would be a key influence.

The most remarkable facts about the book however are Gwenffrwd’s introduction, which contains a direct attack on Cynghanedd, the Welsh poetic tradition of strict metres, and the fact he included twenty of his own poems and translations (a decision for which he modestly excuses himself in the introduction, but which speaks nonetheless to his self-confidence and precociousness).

In 1832 he won a prize at the “Royal Eisteddfod” held that year in Beaumaris; he was one of the poets who were invited to Baron Hill, the house of Lord Bulkley (now a rhododendron-infested ruin in the forest behind the town) to personally receive his prize from Princess (later Queen) Victoria. His poetry continued to appear in magazines and newspapers.

The following year he had moved to Liverpool, but did not stay for long and by the middle of 1833 he was on board a ship bound for the United States. His exact motivation for emigrating is unknown; one source suggests he may have had a drinking problem and had become unemployable in Liverpool, but this will probably never be possible to verify. Whatever the reason, he would not return to Wales.

He continued to write poetry and post it back to magazine editors back in Wales; and it seems reasonable to assume he would have sought out his fellow countrymen in America and may perhaps have intended to return some day; more than one of his contemporaries published verses urging him to do just that.

He spent some time in New York and then Philadelphia – doing what exactly is another mystery – before setting sail for Mobile, Alabama, now a medium sized city but then a town of about ten thousand, but growing quickly. Disease was common in the hot, moist climate, and perhaps an especial danger to a young man used to much colder climes; and tragically in August 1834 Gwenffrwd was claimed by yellow fever at just twenty-three years old. His death triggered an outpouring of poetic elegies in the Welsh press from a country which genuinely felt they had lost a genius.

The obvious tragedy of Gwenffrwd’s youth lent a pathos to the story and there is perhaps an element of hyperbole in the way he was treated by later 19th century poets; and yet as his biographer Huw Williams argues, he is far from being an insignificant figure in the history of Welsh poetry. In the conservative Eisteddfod, Gwenffrwd was an innovator who wanted to see the best of English poetry inform the Welsh poetic tradition.

Whilst the transition to Romanticism can be seen in the work of contemporary figures such as Alun and Eben Fardd (1802–1863), in the work of Gwenffrwd this transition is already complete. His poetry deals heavily with death, loss and grief, and whilst there is undoubtedly an element of following English Romantic fashion here it is difficult not to read biographical element to much of his poetry, as in his numerous, bleakly ironic poems about returning from exile (the first of which he wrote before even leaving Holywell). His long voyage also had an impact and the sea features heavily in his last poems, including the mystical meditation ‘Syniadau ar y Môr’ (Thoughts on the Sea) and a version of the ‘Cantre’r Gwaelod’ story in verse.

Although he perhaps lacks the finesse and formal sophistication of these slightly older poets, he was a more ambitious and daring poet who wanted to upend the existing poetic order. One of the first serious Eisteddfod poets to eschew Cynghanedd altogether, he experimented with imported form such as Blank Verse, and was one of the very first Welsh poets to write a Sonnet (something which wouldn’t really catch on for another century). In content also he was ahead of his time, and his work has a kind of pantheistic mysticism that foreshadows Islwyn (the major Welsh poet of the second half of the nineteenth century), and his lyrics have a personal element which would rarely be seen again before the literary renaissance of the early 20th century. These elements come together in one of his most effective and moving poems, ‘Penillion’ (Verses), the last two of which are as follows:

Syllwn yna ar y nefoedd—

Y lloer ariannai wedd y lli,

A sêr yn siriol yn eu cylchoedd,

Fel yn gwenu arnaf i;

Oddiar y nefoedd gogoneddus

Trois i lawr fy ngolwg ffôl,

Ond nid oedd isod ddrych cariadus,

Trois fy nhrem i’r nen yn ôl.

“Fel hyn,” ymsoniwn, “O! mor ynfyd

Rhed ein serch ar bethau byd,

Tra yn byw yn hardd a hyfryd,

gwên siriol llwydd ynghyd;

Ond pan hulio nos o gystudd

Dros ein llwybrau cnawdol cu,

Pan na fedd daear un llawenydd,

Trown ein trem i’r nefoedd fry.”

[Then I looked up at the heavens—

At the moon lighting up the face of the water,

The cheerful stars in their circles

As if smiling down at me;

Back from the glorious heavens

I turned my foolish gaze away,

But there was no loving mirror below:

So I looked up once again.

“Thus,” I thought, “Oh! So foolish

Our thoughts run to worldly things,

Whilst living in beauty and comfort,

Happy in our success;

And yet when affliction’s night closes in

Around our worldly lives,

And the world holds no more joy for us,

Then we look upon the stars.”

In fact his obvious affinity with this later and most famous school of Welsh poetry – John Morris-Jones, T. Gwynn Jones, R. Williams Parry and the rest – perhaps begs the question why Gwenffrwd isn’t better known and wasn’t championed by these later poets. The answer is relatively straightforward, and lies with Gwenffrwd’s association with one of his own predecessors, the aforementioned William Owen Pughe. A notorious pedlar of linguistic eccentricities whom Morris-Jones accused of vandalism, his influence lies quite strongly on Gwenffrwd, leading to the use of unfortunate words like ‘Ymborfhâu’ (which might be translated as ‘empasture’, as a verb, to mean graze!) and lines like, ‘Hwn beraidd naws a orfelysai’m sedd’ (which I could translate, but not in a way that conveys how far removed it is even from 19th century literary Welsh). These kinds of stylistic oddities affect a lot, though curiously not all of Gwenffrwd’s work, as the clarity of the quotation from ‘Penillion’ above shows.

Whether and how much you will respond to Gwenffrwd depends to a certain degree on your tolerance for such oddities. Yet if you can look beyond them you will find, in Gwenffrwd’s best work, a unique voice and serious contribution to Welsh poetry, and certainly one which deserves to be better known: remarkably, our new volume of his collected published poetical works is the first time ever a whole book has been devoted to his poetry.

Gwenffrwd’s Syniadau ar y Môr: Casgliad o Gerddi is available now from www.melinbapur.cymru and priced at £8.99. Also new from Melin Bapur this week are John Morris-Jones’s Caniadau and Mary Burdett-Jones’s Llanllenorion, both £9.99.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.