Wales and Trinidad: A short history and a modern opportunity

Richard Parry

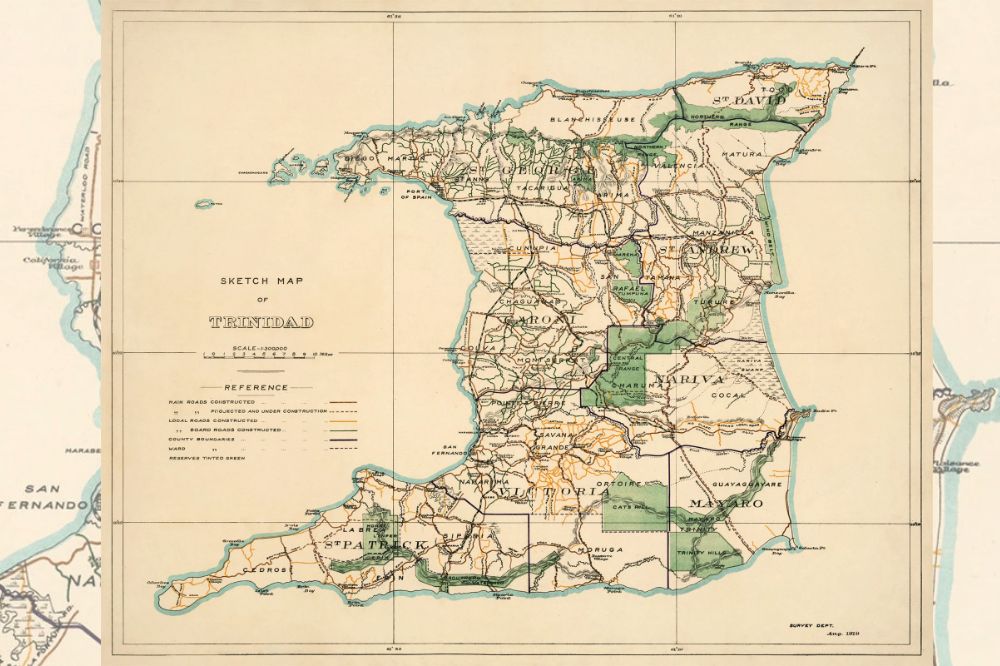

Trinidad and Wales are intimately connected. Take a look at a map. There are villages and places in Trinidad & Tobago named Glamorgan, Pembroke, Mount Harris, Mount Robert and Bethel.

What’s the story behind these names? You’ve probably already guessed – the Atlantic slave trade.

Yes, people from both Africa and Wales travelled to Trinidad in the 18th and 19th centuries.

But the Africans travelled there as brutally enslaved people and were forced to work, whilst Welsh people travelled to Trinidad, with other Europeans, as free citizens hoping to make their fortunes.

Within this history, Wales was particularly connected to Trinidad.

Welsh born Henry Tudor had only been on the English throne as King Henry VII for four years in 1489 when Bartholomew, the brother of Christopher Columbus, arrived in London inviting the first Tudor king to sponsor the Columbus commercial venture across the Atlantic.

Of course Henry, famously, said no. We can only imagine and wonder whether the history of the modern period would have been significantly different if the huge tracts of land we now call ‘the Americas’ had been encountered and explored in the name of a king born in Pembroke castle.

Spain made the project investment. Christopher Columbus found land on the other side of the Atlantic, and ‘discovered’ the island of Trinidad for Spain in 1498.

This claim had unwanted consequences for the people who already lived there. No Spanish colony was immediately established but over the next hundred years Spaniards enslaved many of the Arawak and Carib speaking people from Trinidad, forcing them to work on other Spanish colonial possessions across the region.

Scant economic development took place on the island until the 1770s when Spain began to encourage French settlers to develop Trinidad with slaves. Production and trading of cotton and sugar began.

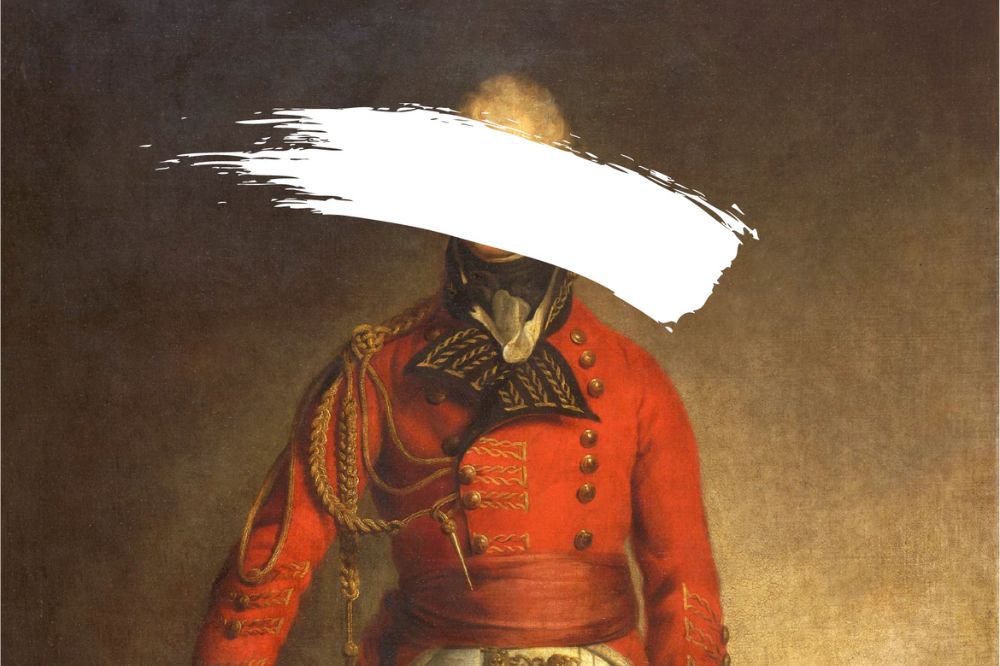

Britain invaded Trinidad in 1797. Pembrokeshire born Thomas Picton was installed as Governor. Generations of people in Wales have known about Thomas Picton from his death in 1815, leading a crucial, decisive charge at the Battle of Waterloo.

Celebrations of his fame following this military death include the Picton obelisk in Carmarthen, a school in Haverfordwest, a memorial in London at St Paul’s Cathedral and the statue in Cardiff City Hall, along with numerous pubs across south Wales called Sir Thomas Picton.

But Picton was a brutal governor of Trinidad, and found himself recalled to London for trial in 1803 to account for his murderous barbarism.

Picton was found guilty of inflicting torture on the poor civilian population, but was never sentenced. At his trial many wealthy colonial settlers from the island spoke in his defence.

Under Picton’s governorship the British occupation of Trinidad from 1797 began rapid economic transformation, underpinned by the Atlantic slave trade. Settlements in Trinidad had Arawak, Carib, Spanish and French names. Now there were added names from Wales too.

Welsh folk went to Trinidad to make their fortunes. Despite Wales’ poverty and neglect, it’s not possible to extricate the story of Wales from the dominant economic story of England.

Wales has both been ‘done to’ in its relationship with England, and people from Wales have also participated in the ‘English project’ and ‘done to’ others. It’s as simple and messy as that.

And Picton didn’t start the transatlantic madness of people in Wales. Welsh adventurers were cashing in on the barbaric game early.

When the Milford Haven born seaman Howell Davis was captured by pirates off the coast of Africa in 1718 he was serving as the mate on the Cadogan, a slave ship.

Davis became a pirate. The following year he captured the slave ship Princess and recruited its second mate, the Newport Pembs born Bartholemew Roberts, who became another Welsh pirate formerly employed as an officer on a slave ship.

Both men died violent pirate deaths, but they may have been inspired by the previous century’s adventurer from south Wales, Henry Morgan, who started off as an indentured labourer in Bristol and ended a career in piracy with being appointed British Governor of Jamaica, receiving a knighthood, and holding significant Caribbean investments of plantations and slaves.

Facing the past

Today Wales is waking up to the extent of past involvement in the fatal history of Europe, Africa and the Americas.

This was pervasive involvement. It touched very widely the economy and daily lives of people in Wales.

Some travelled abroad, and others developed Welsh-based industry as part of the economic system of the day.

Our ancestors from that period are all dead, and today many of us now wonder what might be done. How should we think about this history? What might we do to understand it better, and create a better world because of our better understandings? And many seem too afraid or unwilling to look at the legacy we have received today from this harrowing period.

Looking forward, for a brief moment, perhaps one small thing we could begin to do is remind ourselves that the Future Generations Act in Wales today requires us a nation to pay attention to the needs of the people of the future and hand them a legacy, and an environment, that is not damaged by our current economic appetites and patterns.

We are invited to imagine how the people of the future, across the world, will look upon our generation’s economy, justices and lifestyles. There is a demand to act now. A little thinking in this direction shows us that we are unavoidably connected to the past, and the future.

We have the capacity to make choices for present justice, whatever that points to. The call for justice for the past, can also make us think about justice for the future, and these will both bear on the questions of that justice needed to inform our actions, relationships and lives today.

Under British rule enslaved people arriving from Africa to Trinidad grew enormously. An 1813 census showed that there were then 26,696 people forced to work as slaves on the island, and 13,984 of them had been born in Africa. A large percentage of the enslaved people in Britain’s colony of Trinidad in 1813 had been recently trafficked.

The artist Mary-Anne Roberts was born in Trinidad and came to Britain for the first time in 1982, touring the UK with a Trinidadian theatre company. During her first days in London she was immediately excited to see strawberries for sale on a market stall. She’d never seen actual strawberries before.

Deciding to buy some she went over to the trader and expressed her delight in seeing the strawberries for sale. The market trader said to her, “Oh, I love the Welsh accent, you speak so beautifully! I love Wales” and gave Mary-Anne the strawberries for free. He mistook her Trinidadian accent for a Welsh accent.

Mary-Anne’s first boyfriend back home in Trinidad had been a Rastafarian lad called Llewelyn. Teachers at her school and neighbours had included people with the surnames Davis, Evans, Lewis, Griffiths and Jones.

“When I arrived in Wales I discovered that my surname, Roberts, was Welsh!” says Mary-Anne. “So much of my upbringing in Trinidad took place in a little hidden part of Wales.”

I have been working with Mary-Anne Roberts to create a new opera, exploring the history of the connection between Wales and Trinidad.

An Act of Piracy tells the story of a West Wales man carried away to sea by pirates to Trinidad in the 1790s. The music comprises of classical British sea songs and Trinidadian calypso and folk songs.

Mary-Anne and I are committed to discovering what our friendship and work together means today for Wales as our culture and economy imagines and creates a future relationship with itself and the rest of the world.

Wales has so much insight to offer, and as Mary-Anne’s story shows, Wales and Trinidad still have so many hidden treasures and generosities to gift the world.

Richard Parry is the artist director of the Welsh cultural facilitation organisation Coleridge Cymru.

The new Trinidad /Wales opera An Act of Piracy premiers in South Wales this month: www.actofpiracyopera.org

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

A map of Plaid’s Cymru of the future, Senna has kidnapped Ynys Mon, The South, the separate country it has always been…uncanny but for a while my childhood river powered a busy export business…

Wylfa is now the center of Europe’s nuclear defence industry, HQ in Dublin, thanks to a device developed by a mad scientist from where the Mull of Kintyre used to be, Ynys Mon now floats outside of terrestrial waters and has been declared a Free Radical Universe by the God Rhun, small but perfectly formed, its parliament still sits in Llys John, Aberffraw,

Sadly a frozen relic of a plot between ‘The Trac’, RAF Valley and Paul McCartney’s alter ego, Band, as always, running from something that happened yesterday…

The opportunity to create a dramatic work featuring Ynys Mon, now could not be a better time, if Dr Who would like to get in touch about the above pitch be my guest…

Picton authorised the piqueting of Louisa Calderon. Not a nice man. Found guilty then let off.

You can read a paper of the time here from the National Library of Wales. Cardiff Museum had a display in it. Picton reimagined.

https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3321740/3321744/18/Picton

Have you seen the kit the Yanks have ranged around Trinidad…

B-52s a blast from the past (1956 Bikini Atoll)…

Good old hard power, you can’t beat it apparently…

Britian did not invade Trinidad in 1797. There was intention to. The Treaty of Paris in 1763 put the island down as British along with Tobago, but was then ruled by a Spanish governor. Most of the colonial population being French. General Abercromby for Britain anchored in a bay and upon request the Spanish governor agreed a handover. No fighting. The surrender was under the terms of the treaty which specified that ‘existing customs’ presided. This included slavery. this administration fell on the shoulders of Picton, as new military governor. If we are to examine the history we must first… Read more »

The thing that vexes so many of those who excuse the brutality and sadism that accompanied Britain’s involvement in slavery is that their usual defence of – it was a different time we can’t judge them by our modern standards can’t be applied to Picton.

He w\as judged at the time and found guilty. The streets etc named after him are prime candidates for a name change