Yr Hen Iaith Part 71: Fools without Bounds: The Anterliwt

Jerry Hunter

Full disclosure: I have recently finished a book entitled Llywodraeth y Ffŵl (‘The Rule’ – ‘Governance’ or ‘Government’ – ‘of the Fool’) which examines the relationship between surviving anterliwt texts and the carnivalesque contexts in which these plays were usually performed.

My undergraduate education included a considerable amount of anthropology and folklore – the later an established academic discipline in many countries, if frowned upon in the stuffier corridors of English and Welsh academia – and this included studying folk drama and the seasonal festivals which often provide contexts for such performances.

In many ways, this book – bringing together my love of Welsh literature and my interest in anthropological theory and folkloristics – is something I should’ve written early in my career (if I hadn’t been sidetracked repeatedly by other interests and projects over the years).

I am thrilled to have finally written this book, and, as my co-host Richard Wyn Jones suggests on the podcast, this explains why we’ve devoted a series of episodes to the anterliwt.

However, given the number of surviving texts and the popularity of the tradition in early modern Wales, even a more objective observer might suggest that readers today should know a great deal more about the subject.

Overlap

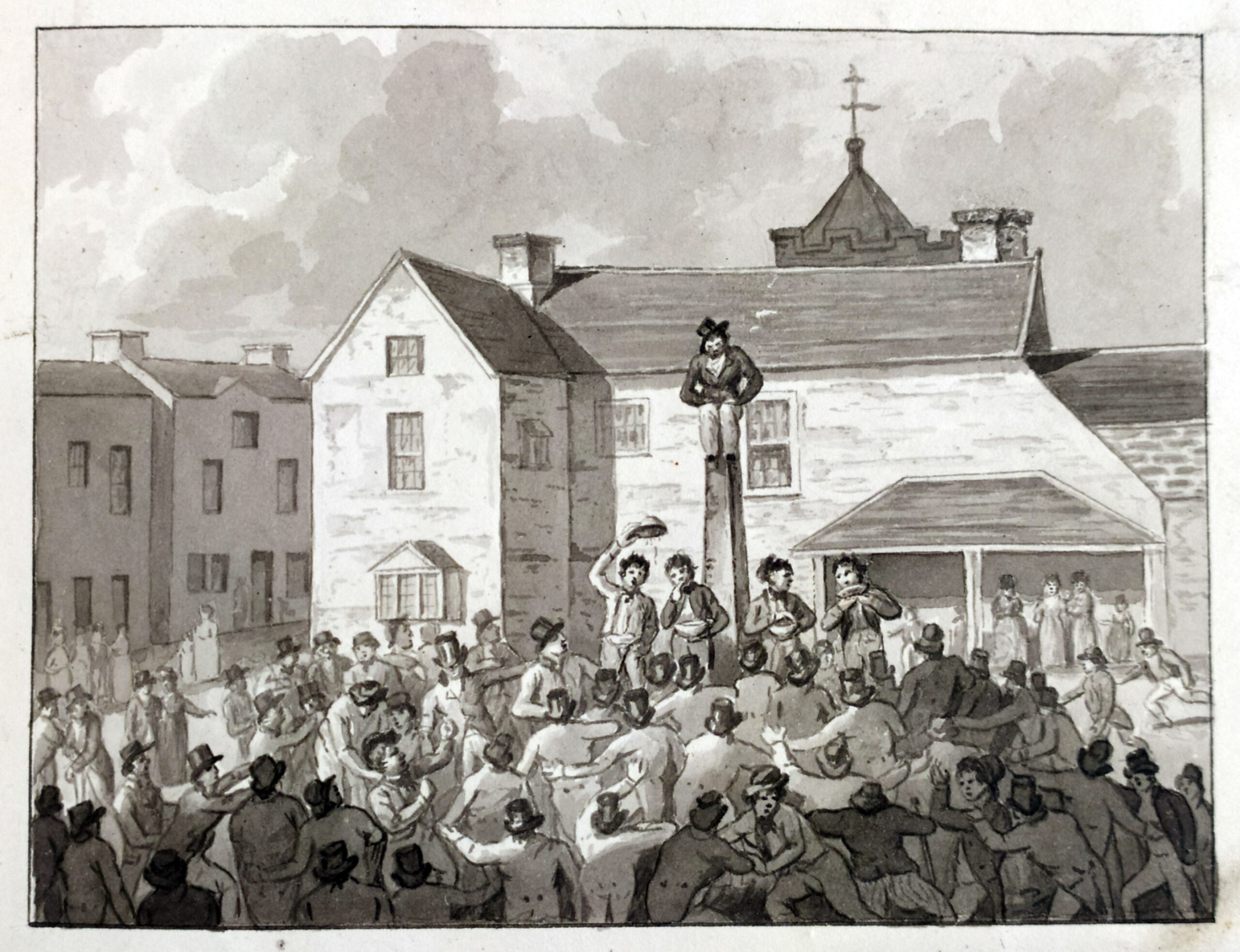

We can locate the anterliwt conceptually at a place where folk drama, literature and popular culture overlap. These plays were written by poets, some anonymous but most of them known, and thus they don’t conform to the strict definitions of folklore and folk drama which many scholars use.

However, we can’t define the tradition without noting the combination of original, scripted play and traditional content. The fool and the miser are the central characters in the traditional layer.

It’s difficult to avoid focusing on the original aspects of each anterliwt. After all, isn’t it the original story which makes each play unique? And, indeed, isn’t it the original story chosen by the poet-playwright which gives each anterliwt its title?

This can lead to a tendency to see the fool and other traditional characters as secondary components, as used parts of an old set recycled in order to stage a new story. People attending a fair, market or gwylmabsant were mostly likely interested in the fact that a new anterliwt by a popular anterliwtiwr (a composer of these plays) was being staged there, but they expected to see the fool. And, indeed, the fool might well have been the character whom they wanted to see the most.

This is why he is the first character to appear in most surviving anterliwtiau. It is the fool’s job to attract the attention of the crowd. His practical function at the play’s start is to turn a mob of festival-goers into an audience, something we can see in anthropological terms as turning disorder into order, anti-structure into structure.

Frivolous One

Let’s take Gwagsaw (perhaps translated as ‘Frivolous One’), the fool in Hanes y Capten Ffactor (‘Captain Factor’s History’) by Huw Jones of Llangwm. He appears on stage, brandishing the fool’s trademark prop, a stick or club shaped like a giant phallus, and he delivers his opening stanza:

Gwaed y Grog lân, fy eneidie!

Mae yma niwl anaele,

A gwragedd yn cerdded yn ddrwg eu naws

Efo’u cywion ar draws y caee.

‘Blood of the holy Cross, my souls [or ‘my dear ones’],

There is a terrible fog here,

And women walking in a naughty way

With their chicks all over the fields.’

Gwagsaw addresses the audience with a term of endearment and utters a blasphemous exclamation all within the confines of his very first line. He then complains that he can’t see very well because of the ‘fog’ (perhaps employing another prop, the comically large spectacles explicitly mentioned by some fools in other anterliwtiau).

However, he can see the women in the audience, whom he suspects are up to no good, and whose children, he implies, might include some born out of wedlock, seeing as they are scattered ‘all over the fields’.

Gwagsaw develops these two themes, spewing bawdy jokes and playing on the concept of ‘seeing’, claiming to have witnessed strange and absurd things in a dream and satirizing the age-old Welsh prophetic tradition. Similarly, the close bond with the audience suggested in his opening line continues.

However, if the fool creates conceptual order by turning a crowd into an audience, he also serves an agent of disorder. During the course of the play, he will introduce chaos into the miser’s life – to such a degree that the miser’s livelihood and life are destroyed. We can see this as a dramatic enactment of a theme common in popular culture, especially the culture of carnival, ‘the world turned upside down’.

This promethean character can even destroy the structure of the anterliwt itself, sometimes slipping out of his own storyline into the play’s other story.

Captain Factor’s story

When the eponymous Captain Factor’s story begins to unfold in Hanes y Capten Ffactor, we see the captain at the London docks talking with two merchants. These men offer Factor a commission and he accepts it gladly; he will take their ship, ‘the Royal Mari’, to Turkey, but they first need to hire a crew to sail it. We are then surprised when Gwagsaw the fool comes on stage and presents himself as a sailor seeking employment:

Gwaed yr eirin perthi!

‘Ewch chwi ar y môr â Mari?

Mi ddof gydach os deil y gêr,

Mae gen-i lester lysti.

‘Sloes’ s blood!

Will you go to see with Mari?

I’ll come with you of the gear holds,

I have a lusty vessel.’

Always fond of double entendre, here the fool pretends to mistake the ship for a real woman named Mari. These lines invite the actor to create visual humour as well; it’s easy to imagine him using his phallic prop as he turns the maritime vocabulary (gêr, ‘gear’ or ‘tackle’, llester, ‘vessel’) into sexual suggestions.

While Captain Factor sees through Gwagsaw, calling him ffŵl pendene (‘a giddy fool’) and advising the others to ignore his lol (‘nonsense’), the merchants are taken in by him, thus allowing the fool to draw out this comic scene. As they question him repeatedly about his sailing experience, Gwagsaw finds ways of inserting additional lewd jokes. The following verse – split between one of the merchants and the fool – finds him playing on the straightman’s words in a different way:

[first merchant:] A fuost ti erioed yn morio?

[Gwagsaw:] Do, unweth, mewn padell, ond gwell f’ase peidio;

Fe’m chwythodd y gwynt fi o Foel-y-llan,

Yn Nulyn roeddwn dan fy nwylo.

[merchant:] ‘Have you ever sailed?’

[Gwagsaw:] ‘Yes, once, in a pan, but it would’ve been better not to;

The wind blew me from Moel-y-llan,

(And so) I was in Dublin twiddling my fingers.’ (lit., ‘under my hands’)

The fool answers a serious question with a version of a traditional rhyme still popular today. The answer is nonsensical, yet it invokes a tradition familiar to the audience, bringing them into an in-joke which is played at the frustrated merchant’s expense.

Seductive wiles

The ffŵl of the anterliwt moves between nonsense and sense, as do fools in many other traditions worldwide (the best-known literary example is surely the fool in Shakespeare’s King Lear). One of the anterliwt fool’s many functions is to address young women in the audience with a song warning them about men’s seductive wiles and advising them not to become pregnant before marrying.

Above all else, crossing boundaries defines the fool’s nature. He repeatedly crosses the boundaries between players and audience, bringing those watching the play into he play itself at various junctures. He crosses the boundaries between the different stories unfolding on that stage. He joyfully breaks social conventions with both speech and actions. And he keeps us guessing as to whether we’ll here sense or nonsense next. And perhaps most interestingly, he moves between opposing functions, sometimes creating order and sometimes destroying it.

As space has only allowed me to quote lines uttered by one fool, I’ll end by naming a few other anterliwt fools: Mr. Atgas (‘Mr. Hateful’), Cecryn (‘Argumentative One’), Dic y Geiriau Pigog (‘Dick of the Pointed Words’), Syr Rhys y Geiriau Duon (‘Sir Rhys of the Black Words’), Syr Caswir (‘Sir Harsh Truth’), and Ffowcyn Gnuchlyd (‘Fucking Foulke’).

This list of names suggests both the traditional character of each individual fool as well as the creative freedom exercised within the bounds of that tradition. That is a good way of thinking about both the fool and the anterliwt in general; both are produced by the dynamic interaction of creativity with traditon.

Further Reading:

- Cynfael Lake (ed.), Anterliwtiau Huw Jones o Langwm (2000).

G.G. Evans, ‘Yr Anterliwt Gymraeg’, Llên Cymru (July 1950).

- G. Evans, ‘Yr Anterliwt Gymraeg [:] II’, Llên Cymru (July 1953).

Dafydd Glyn Jones, ‘The Interludes’, yn Branwen Jarvis (ed.), A guide to Welsh literature c.1700-1800 (2000).

Jerry Hunter, Llywodraeth y Ffŵl: Gwylmabsant, Anterliwt a Chymundeb y Testun (University of Wales Press, appearing in 2026).

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.