Yr Hen Iaith part 74 – Invitations and Exiles: Goronwy Owen

Jerry Hunter

Sometime around the middle of the 1750s, William Parry received an invitation. He worked in the Tower of London as the Royal Mint’s deputy comptroller, and an acquaintance was offering him a break from the city’s dirt and pollution.

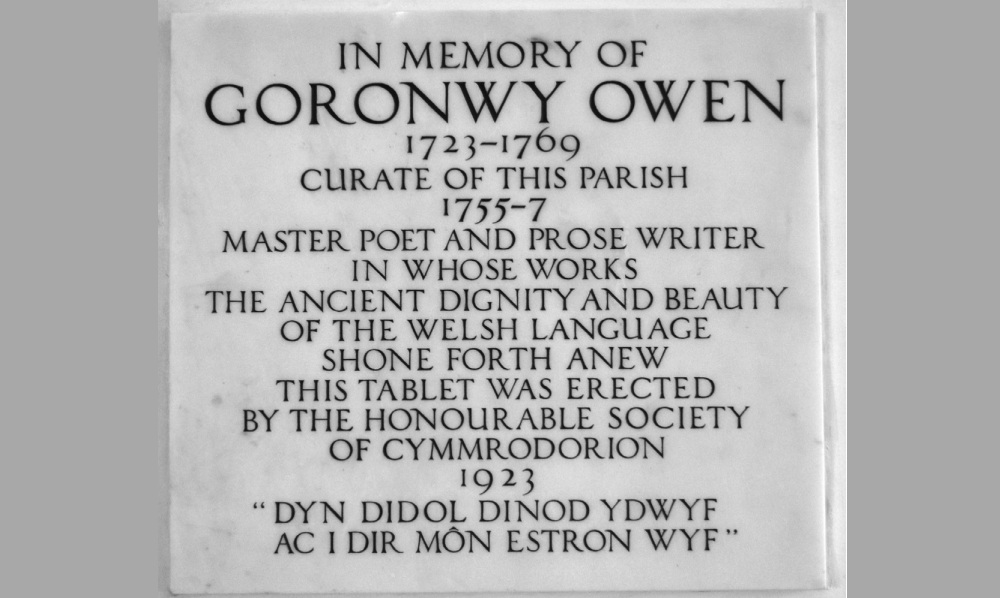

The invitation was to spend some time in Northolt, a small village about ten miles from London, where Parry’s would-be host served as a curate in the parish church. This curate’s name was name was Goronwy Owen, and, like Willim Parry, he was originally from Anglesey.

Goronwy Owen’s relationship with the Morris brothers of Anglesey was complicated. He was from a much poorer background; indeed, his mother worked as a servant in their family house, and given the nature of that extremely hierarchical age, it is no surprise to find a master-servant condescension sometimes inflecting the ways in which the Morrises refer to him in their letters.

They came to deride him for his drunkenness as well. However, the Morris brothers also marvelled at his talent.

After some of Goronwy Owen’s poems began circulating in manuscript, William Morris wrote to his brother Richard in 1752, exclaiming Ni feddyliais i fod y fath ddyn ar wyneb y ddaear, ‘I never thought that there was such a man on the face of the earth’. And in another letter penned in the same year, William dubbed him ‘[G]oronwy Fardd’ (‘the Bard’), and declared that he enjoyed ‘the genius’ (awenydd) of those ancient Welsh bards, Taliesin and Myrddin.

The aesthetic embraced by the Morris circle involved two different kinds of classicism. As was seen in our last instalment, they hoped that contemporary poets might one day reach the technical heights achieved by the great medieval Welsh bards.

Goronwy Owen – who only wrote poetry in the traditional strict metres – achieved an astounding mastery of those complex Welsh forms.

And, as Saunders Lewis declared with the title of his 1924 book, A School of Welsh Augustans, they were also drawn by the themes characterizing Latin poetry from the time of the Emperor Augustus (27 B.C.E. – 14 C. E.).

One of these themes centred on what we might call ‘the good life’, meaning not just a life enhanced by art and pleasure but also one tempered wisely by devotion, study, balance and moderation.

It was surely the connections of the Morris brothers which first enticed Goronwy Owen to London, where became involved in the Cymmrodorion Society which Richard Morris had helped to found.

William Parry, who had worked closely with Richard Morris in a previous job, was one of that London Welsh society’s officers. It is in that context that Goronwy Owen got to know the deputy comptroller of the Royal Mint.

Christian devotion

When Goronwy Owen invited William Parry to come and stay with him, he did it – at least in part – by means of a poem in the cywydd metre. In the first line he address him as ‘Parry, my purest friend’ (Parri, fy nghyfaill puraf, Dyn wyt a garodd Duw Naf).

After completing the couplet be referring to his friend’s Christian devotion, Goronwy Owen then describes him as y mwynwr mau, a phrase which can be translated as ‘my gentleman’ if we take mwynwr as the adjective mwyn (‘kind’, ‘gentle’) and [g]ŵr (‘man’).

However, there is also a noun mwyn which means ‘(metal) ore’, thus providing a nice bit of word play which indexes William Parry’s work in the Royal Mint where the most precious of metals were processed. Later in the poem he describes this work in more detail:

On’d dy swydd hyd y flwyddyn

Yw troi o gylch y Tŵr Gwyn,

A thorri, bathu arian,

Sylltau a dimeiau mân?

‘Is not your job throughout the year

Entail working in The Tower of London,

And form – coining money –

Shillings and little halfpennies?’

He presents the request directly, first asking William Parry to travel ‘from the city over to Northolt (O dref hyd yn Northol draw), and later rewording it mor forcefully using the imperative form of the verb ‘come’:

Dyfydd o fangre dufwg

Gad, er nef, y dref a’i drwg.

‘Come from a black smoky place,

Leave the city and its evil, for heaven’s sake.’

This dualism casting the city as bad and the county as good is manifest in Welsh texts from various centuries and has an ancient pedigree which can be traced back to narratives about Sodom and Gomorrah.

In addition to the healthy alternative to city life which a stay in the country offers, Goronwy Owen details the specific pleasures that William Parry will enjoy when he comes to visit. He will enjoy ‘poetry’ or ‘song’ – cân – ‘and stroll around the little poet’s garden’ (A rhodio gardd y bardd bach).

He is also promised ‘a taste of the master-poet’s bear’ (profi cwrw y prifardd) and ‘the welcome of an honest heart’ (croeso calon onest).

Fellowship

All of these pleasures are richer because of the way in which they are imbued with fellowship and friendship. They two will ‘converse’ (‘mgomio) as they stroll around the garden, ‘observing’ (nodi) together ‘God’s miracle in the splendid fashioning of the leaves’ (Gwyrth Duw mewn rhagorwaith dail).

One theme leads seamlessly to another, as the pleasures of walking in the poet’s garden and studying the flowers leads to religious contemplation. ‘Each flower’ (pob blodeuyn) is ‘like a finger’ (fel bys) ‘which shows man’ (a ddengys i ddyn) that it is ‘God who made it’ (Duw a’i gwnaeth).

The flowers are like described with a different metaphor, aurdeganau gant – they become ‘hundreds of golden’ toys, thus playfully returning to William Parry’s work in the Royal Mint.

In this bardic tour de force, Goronwy Owen turns the ordered garden itself into a metaphor for that Augustan theme, for, in addition to consolidating his catalogue of a good life’s constituent parts (poetry, beer, friendship, nature, religion, etc.), it also stands as a reminder that, just like a good garden where everything is in balance and tended properly, a good life is maintained with an eye to balance and moderation.

Finally, Goronwy Owens turns the garden into a platform for launching another religious theme:

Hafal blodeuyn hefyd

I’n hoen fer yn hyn o fyd.

‘A flower is also like

Our short life in this world.’

The lives of both flowers and people come to an end. Remembering that Goronwy Owen earned his living as an Anglican cleric, it is no surprise that he reminds his friend that a turn towards God is the only antidote for life’s brevity. Assuming that the two will share such goldy meditations during Parry’s stay, the poet also states the two will share a very specific prayer:

Mynd yn ôl cyn marwolaeth

I Fôn, ein cynefin faeth.

‘Returning before our daeth

To Anglesey, our nourishing native habitat.’

Goronwy Owen expressed his hiraeth for Anglesey in several other memorable poems. However, he was not to return to his cynefin or ‘native habitat’.

Virginia

Always in search of a better living, he eventually secured a place at William and Mary College in the British colony of Virginia, his wife and young child dying during the sea crossing.

Despite his ability to produce poetry driven by that Augustan theme, Goronwy Owen’s own life was anything but balanced and ordered. Due, it seems, to his drunkenness and disorganization, he soon lost that position.

By marrying a well-off widow he managed to improve his material circumstances, and he moved to rural Virginia and became the owner of a tobacco plantation. His comparative wealth came at the expense of others; according to his will, he owned four slaves when he died in 1769.

Further Reading:

John H. Davies (ed.), The letters of Lewis, Richard, William, and John Morris, of Anglesey (Morrisiaid Môn), 1728-1765 , two volumes (Aberystwyth, 1907-09).

Saunders Lewis, A School of Welsh Augustans (Wrecsam, 1924).

Branwen Jarvis, Goronwy Owen [:] Writers of Wales (Caerdydd, 1986).

- Cynfael Lake (ed.), Blodeugerdd Barddas o Ganu Caeth y Ddeunawfed Ganrif (Abertawe,1993).

Alan Llwyd, Goronwy Ddiafael, Goronwy Ddu [:] Cofiant Goronwy Owen 1723-1769 (Llandybïe, 1997).

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.