‘His name isn’t Merlin’: Social media creator hits back at mythical misconceptions

A social media creator has hit back against misconceptions about the origins of Merlin, commonly believed to be a mythical wizard from the legend of King Arthur.

“His name isn’t Merlin, it’s Myrddin,” writes Victoria Folkheart, a Welsh mystic and content creator, in her Instagram post. “And he wasn’t a wizard either.”

Over 9,000 people have liked the post, uploaded in mid-January, with 750 commenters largely in agreement.

Explaining how the mistranslation came about, Victoria wrote: “The name itself is an intentional mistranslation. Geoffrey of Monmouth changed it in the 12th century because the Latinised Welsh name ‘Merdyn’ looked too much like the French word ‘Merde’ (Sh*t) to his Norman patrons.

“He swapped the ‘d’ for an ‘l’ and Merlin was born.”

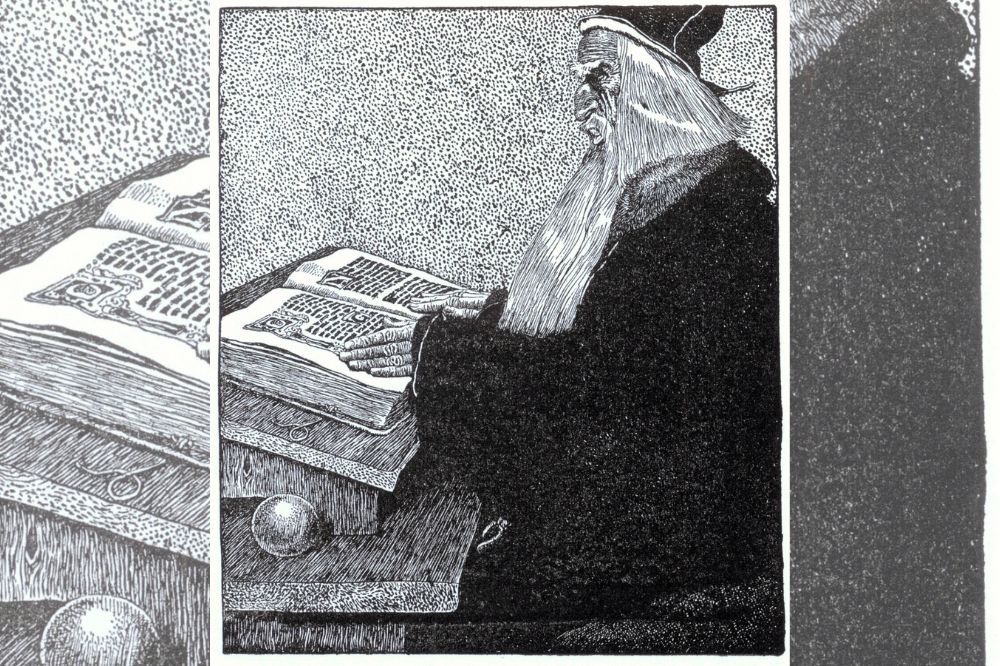

A Catholic cleric, Geoffrey of Monmouth took from various historical accounts to present ‘Merlin’ in the form we know him today — a mad magician and mentor figure to young Arthur.

By combining traditional Welsh stories of Myrddin and another prophet, Ambrosius, he created the composite character Merlinus Ambrosius. Though neither figure had any apparent connection to Arthur, the ‘Merlin’ character was popular in literature and in Wales.

This was further shaped by French writers, such as the poet Robert de Boron, who added to the legend of the wizard, claiming he was imprisoned by the Lady of the Lake after a one-sided romance.

But Victoria also disputes this, writing that in the original Welsh tales: “Myrddin wasn’t a wizard. He was a poet and prophet deeply connected to the natural world – speaking to trees, living amongst wild creatures, channelling visions of what was to come…

“Geoffrey of Monmouth took these Welsh stories, combined them with tales of Ambrosius, relocated the timeline to Arthur’s era, added magical elements, and created the wizard we recognise today.

“But strip away the medieval romance, the Norman embellishments, the Arthurian overlay – and you find the original figure:

“A Welsh bard. A prophet of his people. A man driven mad by war who found wisdom in wildness. A voice crying out from the forest, foretelling the fate of Britain.

“That’s who Myrddin really was.”

View this post on Instagram

Myrddin, in his later form as Merlin, has continued to play a prominent role in popular culture, most notably featured in the Disney movie The Sword in the Stone, which draws from Arthurian legend.

He was also portrayed by Colin Morgan in the eponymous BBC series, which was largely filmed in Wales, as well as England and France.

Geoffrey of Monmouth is also largely credited with the legend of Arthur, who is thought to be based on the Welsh kings Owain Ddantgwyn, Enniaun Girt and Athrwys ap Meurig.

Many commenters agreed with Victoria’s post, thanking her for bringing the legend’s true origins to light.

“Many a name has he and many a corruption placed upon the truth of it… one day we shall all see the truth of Myrddin,” a commenter wrote, while another put it more simply: “Arthurian legend doing cultural appropriation.”

“It begs the question: why couldn’t Geoffrey of Monmouth just transcribe it as Merthin?” Another commenter wondered.

However, not everyone was convinced, with a user adding: “Funny how you’re trying to claim him as Welsh. Back then there were no Welsh people or a Welsh nation.”

Victoria frequently posts breakdowns of Welsh mythical figures on her Instagram, and offers Welsh lessons in a sound-healing setting. You can follow her here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

As one who takes interest in Welsh mythology know the story of Merlin, whose real was name Myrddin, and how the name was altered for obvious reasons by Geoffrey of Monmouth who audience spoke French The same can be said of numerous Welsh character that appear in Welsh mythology used in the Arthurian legend. Take Guinevere, itself a corruption of the middle Welsh Gwenhwyfar, changed from the earlier Old Welsh form, Guinhuimar. It’s good that this author is sparking debate and educating those about Welsh mythology. Normally the original Welsh source is lost. And yes, English & French writers added… Read more »