Why Welsh Colonisation in the Americas deserves to be debated on its own terms

Simon Brooks

Firstly, let me congratulate Geraldine Mac Burney Jones on her recent article, ‘Why the Wladfa in Patagonia shouldn’t be labelled a colonialist venture’. It was lucid, intelligent and thoughtful and by someone from Y Wladfa too.

It was disappointing to see some people on social media engage in a needless pile-on: her view that the Welsh settlement was not a colony because Wales was not a state is not an irrational one. People should be allowed to express rational ideas without being called names.

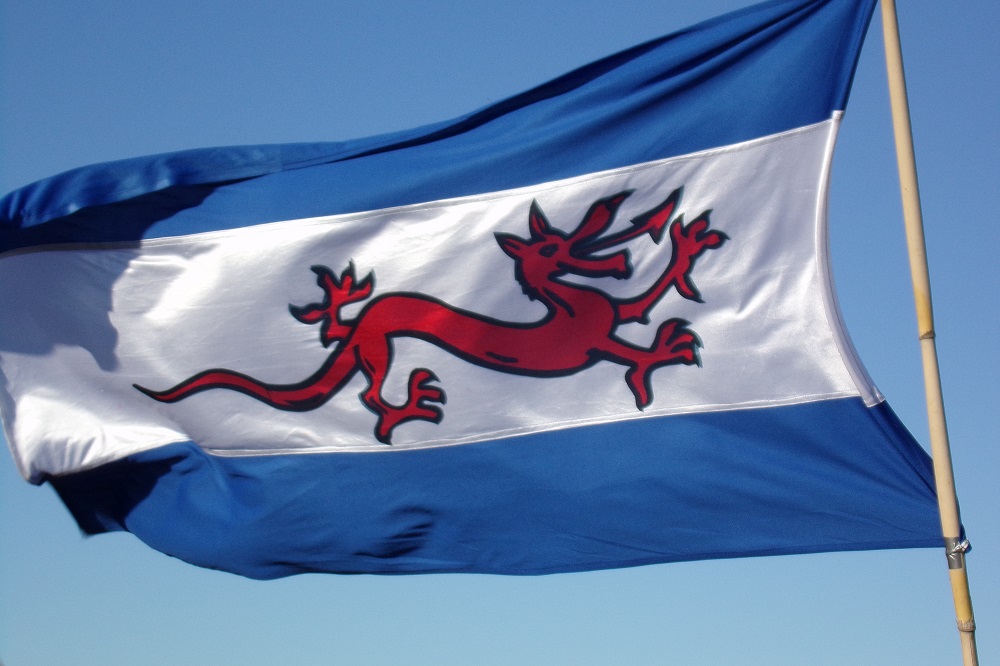

That I disagree with her in part is because Welsh settlement in the New World took place within the wider context of European power, and the Welsh as a European people were fully able to exploit this. It was the intent of Michael D. Jones to establish a self-governing Welsh-speaking community in the New World, and he was fully aware that this would be on indigenous land. In this sense, Y Wladfa was a settler-colony.

However, Geraldine Mac Burney Jones is right to be uneasy about the way the conversation about Patagonia is being conducted in Wales. Settlement carried out by stateless peoples engaging in transatlantic migration is not the same as direct acts of military conquest by state powers. Even if the Welsh, by reaching agreement with Argentina, became proxies of state power, there is a difference. Welsh Patagonians are perfectly entitled to point this out, discuss it and ask what it means.

‘Welsh colonialism’

Too often too, people discuss colonisation by the Welsh as if it was simply a Welsh-speaking version of British settler-colonialism, and again this is incorrect. The Welsh were a minoritised and marginalised people. This led to the development of a very different set of sensibilities, and these became the basis for what we might call ‘Welsh colonialism’ and which we need to attempt to define.

The Welsh of the 18th and 19th centuries viewed themselves as an indigenous people. They believed that they were the original inhabitants of the Island of Britain, and that they had been dispossessed. This was a continuation of a long tradition in Welsh-language thought going back to the early Middle Ages.

Because they regarded themselves as indigenous, Welsh intellectuals became fascinated by indigeneity in general. And European possession of the New World brought a lot of indigenous peoples into view.

The fascination is clear in the Madog myth about which Gwyn Alf Williams has written quite brilliantly, namely the idea that the Welsh had discovered America in 1170 and that Welsh-speaking ‘Indians’ were wandering the continent keenly awaiting a re-union with their brethren in Wales. Even when the myth was debunked, it held powerful sway over Welsh popular culture.

Indigeneity

This then was the intellectual context for Welsh colonisation. All the great radical Welsh thinkers of the late 18th and 19th century believed in Welsh indigeneity to various degrees, and by connection the importance of indigeneity in the Americas: Iolo Morganwg, Morgan John Rhys, Samuel Roberts, and of course Michael D. Jones.

They also all believed in the right of the Welsh to colonise other lands (was not every other nation afforded this very privilege?), and this was central (rather than incidental) to their own radicalism.

They promoted colonisation because it would transfer to the New World a form of self-governing Welsh-speaking indigeneity they felt had been lost in Britain, and by doing so would save it.

This of course is where all the ethical problems kick in. The Welsh took advantage of European expansion to achieve their goal. They had the innate assumptions of European peoples in general that they could do what they liked. If they felt like opening a missionary station or putting up an encampment, they did so.

Hence, we should not be naïve about Welsh colonisation. If Y Wladfa had become an autonomous Welsh-speaking homeland as Michael D. Jones hoped, assimilation within Patagonian society would have been on Welsh rather than Tehuelchian terms. Doubtlessly too it would have been a deeply racialized society. It is important that we do not deny this.

But the Welsh were not interested in pushing indigenous people out. They resisted state actors who wished to do that. To do so would have been a denial of their world-view. They regarded indigenous peoples if not as their equals, then at least as part of their universe.

Each individual example is different, but when we look at Welsh missionaries in the Khasia Hills in India who opposed open abuses of British power, or in the Cherokee nation (where they resisted ethnic cleansing during the Trail of Tears), or at settlers in Patagonia, and missionaries and others in many other places (Madagascar, Polynesia etc), a broadly similar picture emerges.

There is resistance to the more naked forms of colonialism, a peculiar concern with the local language (a reflection of the Welsh obsession with language in general), and an approach to colonisation that favours assimilation (for example, in matters of religion) but not removal.

It is a form of European settler-colonialism. We have to accept that. But it is a different form of settler-colonialism to that practised by the major powers. It deserves to be debated on its own theoretical terms.

Respecting Patagonia

But of course this is not about us anymore. It is 155 years since Welsh colonists set sail for the southern tip of the American continent.

Since that time, the Welsh language has become a language of the Americas. If that be their wish, it belongs to the people of Chubut exactly as French does to the people of Quebec or Scottish Gaelic to those of Cape Breton. It belongs to them as much as it belongs to us.

The presence of the Welsh language in Chubut is the direct result of settler-colonialism. But then that is true of the Spanish language too, as it is of the English language in Canada and the USA. We cannot cherry-pick and say that Welsh in Chubut is ‘bad’ because it is a non-indigenous language, and somehow think that English or Spanish are perfectly acceptable.

People cannot sniff at trips organised by Urdd Gobaith Cymru to Patagonia as somehow ‘wrong’, and then go and watch a Hollywood film. Hollywood is a product of settler-colonialism too.

The Welsh language community in Patagonia today is small, at risk and it is multi-ethnic. It is a minoritised language community and it deserves our support.

Welsh speakers from Patagonia live in Wales and are members of our communities. They deserve the same respect as any other minority group in Wales. That means discussing their heritage in a respectful and courteous manner.

Finally, it is for the Welsh of Patagonia to decide how to describe their own culture. We can contribute to the historical debate because the colonists were from Wales. But in Patagonia, Patagonians and not Walians decide what it means to be Welsh.

It is time we showed a little bit of respect.

Simon Brooks’ forthcoming book, Hanes Cymry, published by the University of Wales Press next year, discusses among other things the nature of Welsh colonialism.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.