Maurice Turnbull: The forgotten story of a Welsh hero

Simon Thomas

When Gareth Bale retired from playing football earlier this year, it reignited the whole debate over who is the greatest Welsh sportsperson of all time.

There’s no shortage of contenders, with the likes of Gareth Edwards, John Charles, Colin Jackson, Geraint Thomas, Lynn “The Leap” Davies, Tanni Grey-Thompson, Alun Wyn Jones and Joe Calzaghe all huge achievers, alongside Bale.

But one name that often tends to get overlooked is that of Maurice Turnbull. Yet here is a man with a unique place in the sporting annals, having been the only person to play rugby for Wales and cricket for England.

He was also an international in hockey and a squash champion, while his contribution off the field was immense. He became a Test selector for England and it’s no exaggeration to say Glamorgan County Cricket Club would not exist today were it not for his efforts in the 1930s.

His life was cruelly cut short at the age of 38 when he was killed in action in France in 1944 during WWII. But he had already packed so much into that life.

Someone who knows his story better than just about anyone else is Glamorgan CCC’s historian Andrew Hignell, who wrote a book on the great man.

So what is it about Turnbull that made him want to find out more?

“It was a forgotten story of a hero,” he explains.

“I had seen his name mentioned in a lot of places, but there was no real definitive history of his life.

“Fortuitously, at the time my wife was the headmaster’s secretary at Downside School, in Somerset, which was Maurice’s old school.

“So I thought if I’m ever going to be able to write the story, it’s now.

“I had access to the archives there and there was also the old boys society.

“Through them, I got in touch with his son and his two daughters and met up with them. They were so supportive. They knew fragments of their father’s life, but there was nowhere you could see or hear the full story.”

It was a tale that began in 1906 when Turnbull was born in Cardiff. He grew up in the Penylan area of the city and took his first sporting steps on Roath Rec.

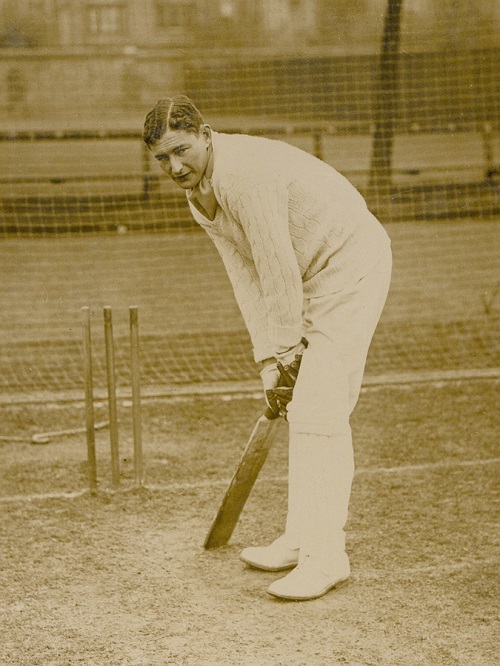

His all-round talent soon became apparent, particularly so with cricket, and he made his Glamorgan debut as a schoolboy in 1924.

A gifted right-handed middle-order batsman, he went on to captain Cambridge University, where he also won a Blue in hockey.

MCC

Selected for the MCC’s 1929-30 winter tour of Australia and New Zealand, he made his England Test debut against the Kiwis in Christchurch in January 1930.

Later that year, he began a ten season stint as skipper of Glamorgan, ahead of touring South Africa with England in 1930-31.

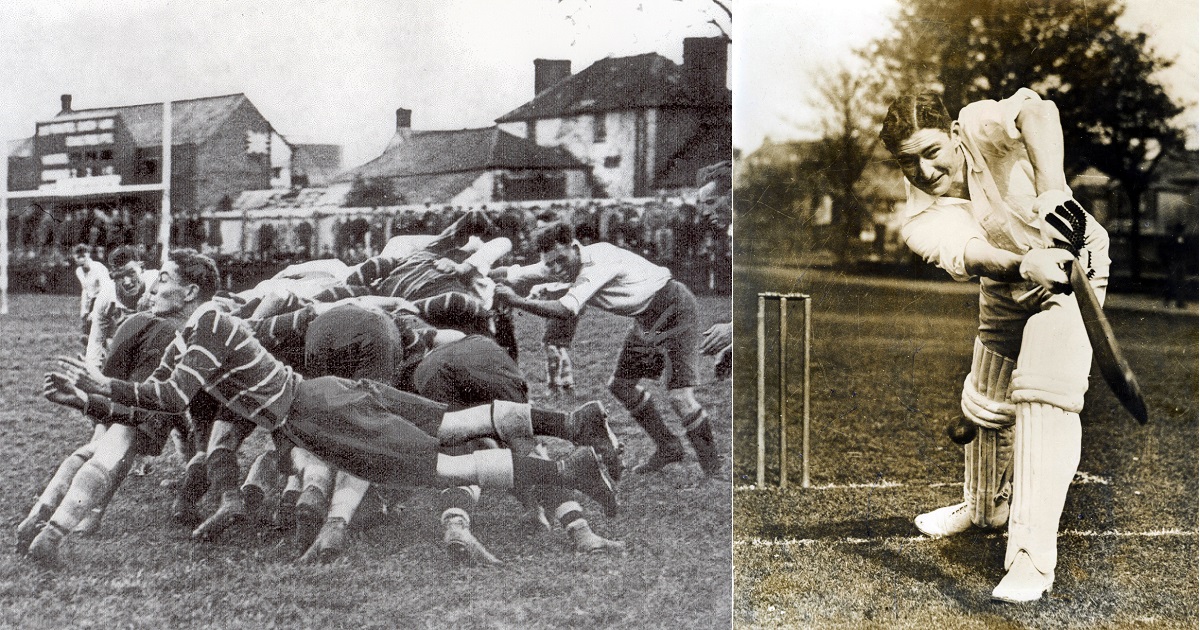

Then there was the rugby. A scrum-half for Cardiff and London Welsh, he was to win two Wales caps in 1933.

On his debut, in the January of that year, he was part of the first Welsh team to beat England at Twickenham, while he started once more against Ireland in Belfast later on in the Five Nations campaign.

He also represented his country at field hockey and was squash champion for south Wales, following in the footsteps of his father, Philip, who won a hockey bronze medal at the 1908 Olympics.

It was an extraordinary sporting family, with five of Maurice’s brothers also playing for Cardiff RFC.

From the mid-1930s, Turnbull focused firmly on cricket.

“He just had too many injuries, so 1934 was his last year of rugby,” said Hignell.

“I think he realised his body probably couldn’t cope with playing both sports any longer. He had an ongoing knee problem.

“I think he was worried what the impact on his cricket career would be if he picked up another major injury because cricket was his number one.”

Turnbull passed 1000 runs in a season ten times and hit three double-centuries, while he won nine caps for England in all, his last Test coming against India at Lord’s in June 1936.

As for his role with Glamorgan, well it’s hard to fully appreciate just what a big figure he was on the Welsh sporting scene.

Hignell provides one particular story to illustrate his stature.

“Towards the end of the 1932 season, Glamorgan played Nottinghamshire at the Arms Park,” he says.

“The word spread that their fast bowlers Harold Larwood and Bill Voce were going to experiment with the bodyline tactic they were to controversially employ on England’s tour of Australia that winter.

“So a big crowd turned out, including a young John Arlott, who came to watch his boyhood hero, Maurice, face the quick bowling.

“Well, every time the ball came short, Turnbull was hooking, cutting, pulling. He was about 170 not out overnight.

“Somewhat chastened, the Notts players went into the pubs on Westgate Street after the day’s play.

“The story goes that at about 11.30pm, a group of them decided to clamber back in over the gate and water the wicket.

“Unfortunately for them, the groundsman was still there and there was a bit of a scuffle.

“Maurice received a message about the incident while dining at the Grand Hotel across the road. He went over and saw these rust-coloured patches on the pitch and an upset groundsman.

“The Western Mail reporter had got the story, so Maurice went down into the Western Mail offices to see the night editor. He said ‘You can not run this story’ and it got pulled. That was how highly regarded he was.”

Fight for survival

It was in the winter of 1932-33 that he made his greatest contribution to Glamorgan, who were facing a financial fight for survival.

“He saved the club,” declares Hignell. “He led a fund-raising campaign to keep it alive.

“If it wasn’t for Maurice and Johnny Clay, there wouldn’t have been a Glamorgan Cricket Club. The club would have folded. It was in a perilous position.

“But Maurice was determined it should survive. That was the single-mindedness of the man.

“And remember this was at a time when he was also playing rugby for Wales. It was an extraordinary effort.”

In a way, that kind of non-stop activity on multiple fronts summed Turnbull up.

“He had incredible energy and such vision,” said Hignell.

“He was the driving force behind Glamorgan, but he also ran an insurance brokerage and was a journalist, working for the Welsh Catholic Times, as well as writing pieces for the national press and two books on cricket.

“He was also the unofficial leader of the Catholic community in south Wales, going over to Ireland as part of a delegation for the Pope’s visit.

“He had a devout Catholic faith and there are mantras within that faith about service and doing your best. He really transferred that into his sporting life.”

Kindness

What Hignell also became aware of was the kindness that was an intrinsic part of Turnbull’s make-up.

“The biggest thing I learned from reading his diaries was he was such a sensitive and well-meaning man,” he says.

“At the start of the 1934 season, Glamorgan’s wicketkeeper Trevor Every had a bad game behind the stumps. He said he was having difficulty seeing the ball, so Maurice arranged for him to go to the infirmary.

“It turned out he had a degenerative condition and within six weeks he was blind, at the age of just 25.

“Maurice led a fundraising campaign for Trevor to retrain as a stenographer with the Royal National Institute for the Blind. He organised a couple of rugby and football matches.

“In the same year, his old headmaster was retiring from Downside. So Maurice arranged for the Somerset v Glamorgan county championship match to be played at the school to say thank you to him. It’s the only county match ever staged by Somerset there.

“It was this kind-hearted nature that really came across in his diaries and the letters he wrote.

“He always put other people first and he certainly put the team first when he was captain of Glamorgan.

He played a huge part in turning round their fortunes both on and off the field in the 1930s.”

In September 1939, he married Elizabeth Brooke and they were to have three children, Sara, Simon and Georgina.

With the onset of the war, Turnbull was commissioned into the Welsh Guards, rising to the rank of major.

Tragically, he was killed in August 1944 during intense fighting for the French village of Montchamp following the Normandy landings.

Leading a small group of Guardsmen in a bid to disarm a tank, he died instantly when the tank’s gun turret swung around and fired through the hedge he was crawling alongside.

“When Maurice got shot, the Welsh Guards retreated back to their base,” said Hignell.

“A group of them decided to go back and try and recover his body. They said we can’t have a great man lying there.

“So they went back, ripped a door off one of the outbuildings of a farmhouse and carried his body back.”

Turnbull is buried at the Bayeux War Cemetery, while there is a memorial to him on the family grave at Cathays cemetery in Cardiff.

Hignell strongly believes more should be done to remember this great man.

“Here is this iconic person and you just don’t see any physical memorial to him,” he says.

“Why isn’t there a blue plaque on the house in Penylan? There should be a statue to him here in Cardiff somewhere.”

And, finally, what about Turnbull’s claim to be Wales’ greatest sportsperson?

“He should certainly be in the discussion,” says Hignell.

“He was a man of his generation. In the 1930s, you could play winter and summer sports to a high level.

“To have played cricket, rugby, hockey and squash at international standard is quite remarkable and all as an amateur.

He really was a man of his time and a true Welsh sporting great who shouldn’t be forgotten.

“In 38 years, he achieved more than many people achieve in 88 years.”

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Great article more like this please da iawn Nation.Cymru