The story of rugby’s most famous commentary and THAT try

Simon Thomas

It’s the most famous piece of rugby commentary of all time and in the eyes of most people it’s absolute perfection.

But that’s not how the man who actually spoke the words saw it.

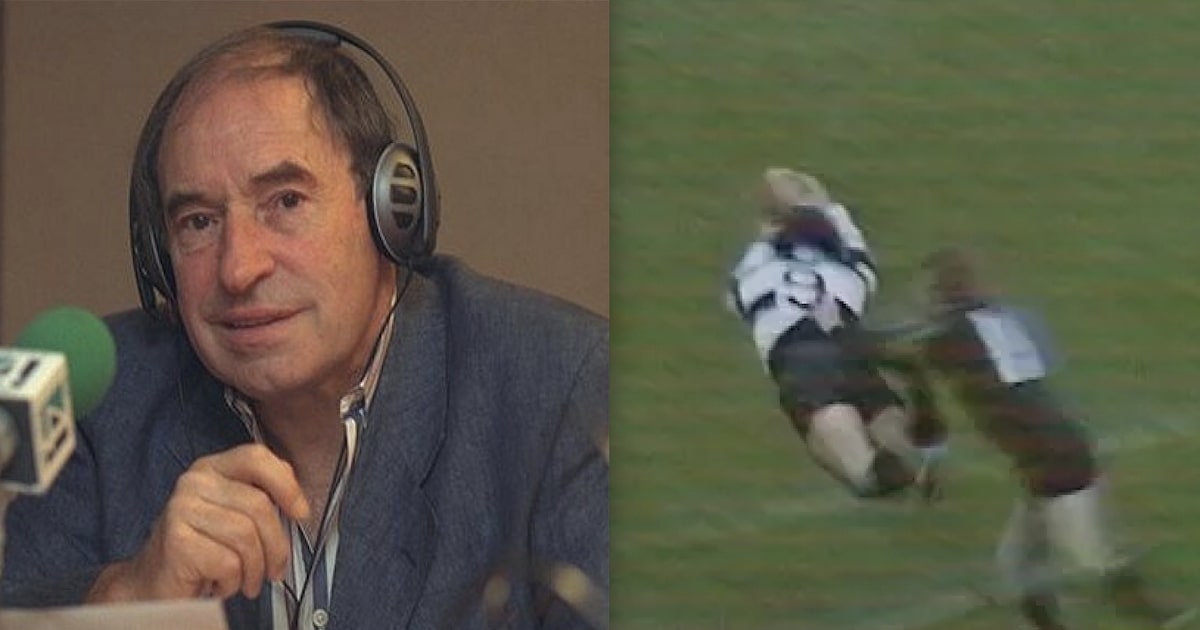

We are, of course, talking about Cliff Morgan’s legendary description of THAT try by Sir Gareth Edwards in the 1973 Barbarians v New Zealand match at the old National Stadium, Cardiff Arms Park.

It is the stuff of rugby folklore, with the commentary still striking a chord today even on the umpteenth listen.

Just four minutes into the game, it all began as All Blacks winger Bryan Williams kicked infield from just inside his own half.

Morgan then took up the tale, as a double side-step from Phil Bennett set the counter-attack in motion and history unfolded.

“This is great stuff, Phil Bennett covering. Chased by Alistair Scown, brilliant, oh that’s brilliant. John Williams…Pullin, John Dawes, great dummy, David, Tom David. The halfway line, brilliant by Quinnell. This is Gareth Edwards, a dramatic start. What a score!”

Those hairs on the back of the neck still tingle. Now, as the 50th anniversary of the greatest try of them all approaches, the inside story of Morgan’s commentary can be revealed.

The former Wales and Lions fly-half passed away, aged 83, in 2013, but the tale lives on through those who knew him well.

One of those people is leading modern-day rugby commentator Nick Mullins who worked with Morgan at BBC Radio in the early 1990s.

“I first arrived as a producer and when new producers came into the sports room at the BBC, you would work across all of the BBC radio networks, One to Five,” he recalls.

“They always liked to throw the new kids towards Cliff within the first couple of months as a kind of make-or-break. He was presenting the Sport on Four programme at the time.

“So I was his producer for six months in 1993, which coincided with the 20th anniversary of the 1973 game and we came up with the idea of going to talk to everybody involved in the try. With Cliff’s commentary as well, he could book-end it.

“I would always drive with him to the interviews, so that’s how we got to talk about the try as much as we did.”

The first thing Mullins learned was that Morgan wasn’t meant to be commentating on the match at all.

“Bill McLaren fell ill the day before the game, so Cliff was called in at fairly late notice,” he explains.

“Otherwise, it would have been Bill’s commentary and I often wonder what he would have done with that try. I am sure he would have dressed it up wonderfully in his own way.”

Extraordinary

As Mullins outlines, there is a further startling twist to the tale.

“More extraordinary than almost anything else is that Cliff did that commentary less than a year after suffering a stroke,” he said.

“It took him four or five months to fully recover his speech. He lost control down the left side of his body. He went through a fairly extensive course of speech therapy while he was recuperating in hospital.

“What we hear in that commentary is his brilliant poetry and the musicality of his voice, but six, seven months before he was still slurring, he really couldn’t speak properly.

“That makes it all the more extraordinary really that he was able to deliver that less than a year after losing the power of speaking properly.

“He was only just working his way back into the business because of the time out he had following his stroke in March 1972. He would have just been rebuilding his career as a broadcaster. That’s the background against which he delivered that superb commentary.”

Yet Morgan was never fully satisfied with what he came up with on the day.

“He would talk about that commentary all the time and how it always rankled with him that the phrase we all remember – ‘What a score!’ – is the one he actually wished he’d never said,” reveals Mullins.

“His view was that we could see that. He thought it was superfluous. He always wished he’d finished with ‘A dramatic start’.

“I think he was really happy with the commentary overall. He felt he’d done that moment justice, but he just felt that last phrase was an extra dollop of cream that it didn’t need.

“We would argue about it all the time and I would disagree and I’m sure a lot of people would. But it’s the way Cliff felt about it. He just didn’t think it was needed.

“His view was always that unless what you had to say was better than the sound at the time – 60 odd thousand inside the Arms Park going bananas at that try – then let’s just listen to that. I think that was the gist of it, rather than necessarily the words he used.

“It was the noise of the stadium which he felt would have been more arresting than those final few words. I could never persuade him that actually it was a reasonable way of rounding off the commentary.”

Mullins continues: “There was an alignment of the stars that day with Cliff, given who he was, his background and just the way he was as a broadcaster.

“Clearly, rugby was his passion as a player, but he brought so much into broadcasting that we heard that day in his commentary, particularly in that snippet we hear so often.

“He just loved the prose and the poetry and the music of Wales. When I hear that commentary, that’s certainly what I hear. I just hear Cliff and it reminds me so much of those conversations we’d have in the car.”

Morgan was Head of BBC Sport and Outside Broadcasts in the 1970s and 80s before focusing on radio, where his mellifluous voice and conversational style made him such an engaging listen.

He certainly had a big influence on Mullins, who has become a top commentator himself with the BBC, ITV and BT Sport, covering a number of sports, but particularly rugby.

“I learned more from him in six months than I would have done in 600 years with anybody else. The bloke was just a genius,” he says.

“He was the last person at the BBC to be able to do two things. One was to type on a manual typewriter. You would always hear the clatter of the keys whenever you got out of the lift on the third floor of Broadcasting House at whatever ungodly time on a Saturday morning. He never really mastered email and loved his old typewriter.

“The other thing you would notice was the smell of smoke because he was the last person in the BBC allowed to smoke in the building without being kicked out.

“Cliff was a big letter writer and we kept in touch over the years. Still today, his autobiography is something I turn to every now and again for some wholesome goodness just to remind myself what the game used to be like.

“I will always be full of thanks to Cliff and to Bill (McLaren) who were so supportive to all of us young whippersnappers who were coming up through the BBC at the time.”

So now for the really tough question. Who was the greatest rugby commentator? Cliff or Bill?

“I don’t have any issue with answering this because I would just turn to Cliff and he would say Bill was the greatest – and he remains the greatest,” replies Mullins.

“The big difference between them as commentators was how sparse Cliff was with the words he used.

“If you listen back to that commentary on the Baa-Baas try, however long it lasts for – 30 to 35 seconds – I don’t think there was a sentence within it that contains more than four words. There is clearly an awful lot of name-calling, which is essentially what he’s doing.

“Cliff was a beautiful writer, but he was a very sparse writer as well. For all that he loved the poetry and musicality of it all, he never used three words where he could get away with two.

“When I think of Cliff, the first word I think of is joy. That was the word he used more than any other.

“He would say ‘Where is the joy in this interview? Where is the joy in what we are doing?’ and I think you can hear that in that commentary and you can certainly hear that when you listen back to whatever Bill was doing.

“There was a lack of the cynicism we have all been imbued with these days. Neither of those two had that when it came to talking about rugby. I will bow to Cliff, who I am sure would bow to Bill, who remains the standard setter.”

Reflecting finally on Morgan’s timeless description of the try of tries, Mullins says: “My favourite line of all from that commentary is actually the one at the end that more often than not gets cut off in the edit which you might see on social media. That’s when he says ‘Oh that fellow Edwards’.

“It sums Cliff up really. It’s his love of the game and his love of Gareth as well because Gareth was his favourite player and it all came together in that moment for Cliff, I think.

“Commentating on the team he loved playing for, in the stadium he loved to play in and a try scored by the player he loved watching the most of all.”

Match Facts

Barbarians 23, New Zealand 11

(January 27, 1973; National Stadium, Cardiff)

Barbarians: JPR Williams (Wales); David Duckham (England), John Dawes (capt, Wales), Mike Gibson (Ireland), John Bevan (Wales); Phil Bennett (Wales), Gareth Edwards (Wales); Ray McLoughlin (Ireland), John Pullin (England), Sandy Carmichael (Scotland) Willie John McBride (Ireland), Bob Wilkinson (Cambridge University), Tom David (Llanelli), Fergus Slattery (Ireland), Derek Quinnell (Wales).

Tries – G Edwards, F Slattery, J Bevan, JPR Williams; cons – Phil Bennett (3); pen – P Bennett.

New Zealand: Joe Karam; Bryan Williams, Bruce Robertson, Ian Hurst, Grant Batty; Bob Burgess, Sid Going; Graham Whiting, Ron Urlich, Kent Lambert, Peter Whiting, Hamish Macdonald, Alistair Scown, Ian Kirkpatrick (capt), Alex Wyllie.

Tries – G Batty (2); pen – J Karam.

Referee: Georges Domercq (France)

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Cliff Morgan was very well like and respected. He accepted an invitation from Cymdeithas y Mabinogi, the Cambridge University Welsh Society ( 1966?) to come to talk to us. Not only was the talk very good but he insisted on buying everybody in the audience a drink