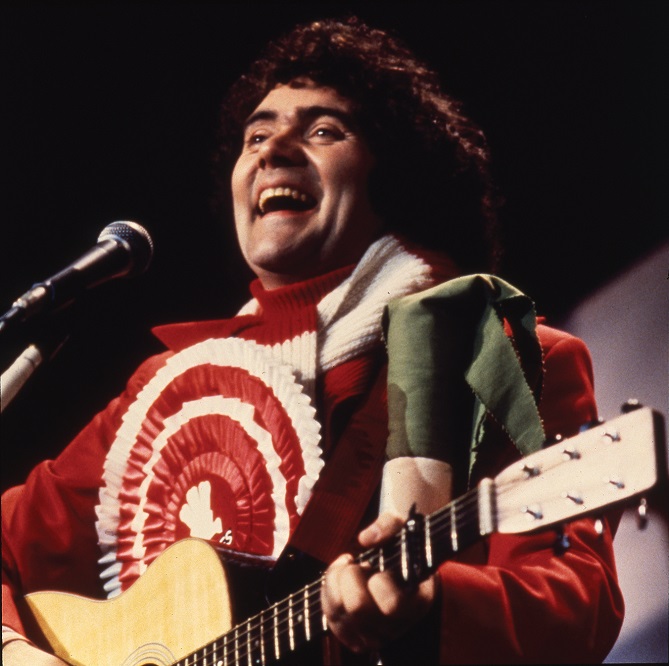

When Max Boyce met the Dallas Cowboys

In an exclusive extract from his new book Max Boyce: Hymns & Arias – The Selected Poems, Songs and Stories, we get the lowdown on Max’s not entirely successful try-out for the NFL’s Dallas Cowboys In 1982.

Little did I know what I was letting myself in for when I agreed to take part in a film about ‘gridiron’ football in America.

It followed Jasper Carrott’s hilarious film by the same company, Opix Films, about his experience with an American soccer team called the Tampa Bay Rowdies.

The team we were to involve ourselves with was the Dallas Cowboys.

This was a few years before the sport had gained popularity in Great Britain, and the film was designed to explain, inform and generally whet the appetite of the new Channel 4 public.

I freely admit that at the time the Dallas Cowboys meant little to me, but the prospect of studying and getting to know the game in America intrigued me.

Such is the thoroughness of the Cowboys’ system that before they agreed to the making of the film they wanted to establish my suitability. The Vice Chairman of the Dallas Cowboys, a Mr Joe Bailey, came to London and a lunch meeting was arranged. We talked and, loosened up by a few beers, shared a few stories.

I ended up much later learning a gridiron move or ‘play’ called Blue Toss 39 Right on Two which resulted in me ‘rushing’ eighty-five yards (after an interception outside Fenwicks) for a touch-down at the junction of Carlisle Street and Dean Street. Joe kicked the extra point.

Real ale

Suitably impressed by my balanced running and my knowledge of real ale, he declared me suitable.

Later that week I met Gareth Edwards following the England–Wales rugby international at Twickenham. I mentioned that I was going to Dallas to have a look at American football and that I was desperately keen.

‘Well, whatever you do, Max,’ Gareth insisted, ‘don’t get involved.’

‘But what if I train hard and lose weight?’ I argued.

‘You’ll get killed.’

‘But what if I take steroids?’

‘They’ll walk all over you.’

‘But what if I paint a dragon on my helmet?’

‘Ah!’ said Gareth, weighing it up. ‘That’s different.’

I laughed and he wished me well.

Thus forewarned, the next week we flew into Dallas. I was interviewed on arrival by a local film crew, and in my eagerness to please, sang them a little ditty with a suitable Southern drawl.

We flew into Dallas and I tell you all so far

I ain’t seen Miss Ellie yet and I sure ain’t seen J.R.

And I ain’t been to Southfork, the ranch that’s on TV,

But I’m with the Dallas Cowboys and that’s good enough for me.

They said I was ‘kinda cute’ and then enquired what position I was going to play.

I hadn’t appreciated that the producer – because of his enthusiasm for the project – had omitted to tell them I had never seen, let alone played, American football. I wondered why many of them stared at me and slowly shook their heads.

They had understood that I was a well-known name in British rugby, but no one had told them in what capacity.

I kept hearing whispered conversations, and comments like ‘He’s kinda small, ain’t he?’

After a few days’ acclimatisation in Dallas I was asked to undertake a searching medical examination, including the delicate question of possible impotency. Apparently, this was not uncommon amongst gridiron players following long and rigorous weight training schedules.

After the medical, I was asked to go on a fifteen-mile run so that doctors could ascertain my physical condition on return.

When I did eventually return, my face like a red pepper, everyone had left the building, the place was in darkness and I was presumed lost . . .

The next day I was introduced to one of the coaches and given my play-book, the ‘bible’ of the gridiron player, where every set move or ‘play’ of the side was listed and diagramatically drawn. There were over 250 of these so-called ‘plays’, each of which had to be memorised perfectly.

Knitting pattern

Some of them were fairly straightforward, but others were incredibly complex and resembled a knitting pattern. I shuddered at the thought of playing a vitally important match, a ‘play’ being called by the quarter-back, and finding myself having to ask which one it was. I resolved I would learn as many as I could, and that night I went to sleep with the ‘bible’ by my bed.

After a few days in Dallas, which I found to be one of the friendliest places I have ever been and totally unlike its television image, we flew to the Dallas Cowboys’ training camp in California.

The reason the training camp was in California, some thousand miles away, was because the intense heat in Texas at that time of the year made it quite unbearable.

The training camp used by the Cowboys was a college campus in the foothills of the mountains at a place called Thousand Oaks, some thirty miles north of Los Angeles.

I shall never forget that first morning being introduced as an athlete-cum-entertainer from England who was going to try out for the Cowboys.

I looked around at these huge men with some apprehension and wondered, ‘What am I doing here?’

One of them approached me and said, ‘You’re kinda small to be in the trenches, ain’t ya?’

I said, ‘I haven’t been very well . . . !’

He just smiled and said, ‘You’re gonna get worse . . .’

I was then taken to the kit room by a friendly Texan known as ‘Cotton’ because of his straw-coloured hair.

Unlike in most games, each player is allocated a number, and mine was to be ten, which I was thrilled about. I explained with boyish exuberance that this number had a special significance in Wales, being the number worn by the outside-half in rugby, and that we had a great tradition of them with players like Cliff Morgan, Phil Bennett, Barry John, etc.

They looked blankly at me and obviously hadn’t heard of any of the people I had mentioned – in fact knew virtually nothing about rugby football.

‘Tell me, Max,’ one asked. ‘Why is it that people who play rugby haven’t got any teeth?’

I answered, ‘It’s to stop them biting each other.’

He looked at me astonished. ‘You don’t say.’

They were without exception in total awe of rugby football, and kept saying they wouldn’t dream of playing it.

‘Those guys don’t wear any pads.’

I was then given all the necessary protection, the huge shoulder pads, forearm pads, thigh pads, knee guards and my helmet. It had three or four steel bars forming a grille across the front, which I thought would have made it impossible to catch the ball or even to see it properly.

They explained it was a ‘linebacker’s’ helmet (gridiron’s equivalent of a front-row forward in rugby) and in that position the ball was purely incidental. I found it quite astonishing to be told that linebackers could go several seasons without handling the ball at all.

For my first few days I was to be part of the defensive line-up and to find out what it was like to be ‘in the trenches’.

The first thing I was shown was a helmet slap, which in effect was a legal short-arm tackle delivered with the extended forearm to the side of the head.

I foolishly asked this huge player, a man of Irish extraction called ‘Fitzy’, to illustrate this. I was keen to know what degree of protection the helmet afforded. He chuckled, shrugged his shoulders and hit me clean over a bench into one of the changing lockers.

The film director shouted excitedly, ‘Great! Great! Can we do that again on a wide angle . . . ?!!!’

Fitzy helped me out of the locker and enquired, ‘You OK?’

He appeared slightly out of focus, but naturally I insisted that it hadn’t hurt at all and that I was looking forward to playing ‘in the trenches’!

Before each training session every player was taken to be weighed and strapped up. Every joint was strapped with tape to minimise the chance of injury. After my experience in the dressing-room, I was quite relieved to hear this and ended up some twenty minutes later resembling something from an Egyptian tomb.

This, coupled with all the protective gear, made movement very restricted but after my flirtation with the locker I was quite prepared to put up with any discomfort.

Rookies

This was the first time I had seen the rest of the ‘rookies’ – the other new players who were at the training camp hoping to become ‘Dallas Cowboys’. There were some forty to fifty of these rookies, who had been ‘drafted’ from colleges all over America after being watched in college games by the network of Cowboy scouts that covered the whole country.

I found the method of drafting players fascinating. Apparently the side that finishes in bottom position in the league is given the first choice of new college players in the following season. The team finishing in first position in, say, a league of ten would be given the tenth choice, and then it’s the turn of the side finishing last to choose their second player, and so on. This process is repeated until forty or so college players have been selected by each professional side.

This seemed a very democratic system and was similar to the way we chose teams as youngsters in the park or the school yard. There two captains were picked, a coin was tossed and whoever won had the choice of the best player.

Despite the undoubted fairness of this method of selection, it seemed to me a little harsh on the individual player’s freedom of choice. I was also astonished to discover that, out of the forty or so college players selected by the Dallas Cowboys, only three or four on average would be retained at the end of the six weeks at training camp. They would then go on to become professional footballers with the Dallas Cowboys.

This, for many of the rookies, was to be the most important few weeks of their lives. For the established players, or ‘veterans’ as they were known, these rookies represented a threat to their place in the team.

Fined

Each morning would start with breakfast around eight o’clock and then we would be weighed and strapped up. Any player sustaining an injury through not having been strapped would automatically be fined.

The morning session lasted from nine until twelve, and after lunch, vitamin pills and salt tablets there was a further afternoon session from two until around five. This was followed by a sort of night school from seven until nine, involving talks and lectures.

There was very little, if any, of the beer drinking associated with rugby football, and in fact most players were glad to be in bed by ten o’clock. However, coaches were sent around our ‘dormitories’ at ten to check if indeed we were ‘home’. Any ‘vet’ not answering his late night call would be fined. There were occasions when some of the vets (whose place in the team was assured) never came ‘home’ at all and during the evening class of the next day were fined very heavily and subsequently disciplined (much to the joy of the rest of the squad).

In these evening classes I found it almost impossible to stay awake, not because I wasn’t interested; I was so desperately tired.

The training schedule was carried out six days a week and subsequently I found myself absolutely shattered attempting to keep up with the other rookies, who were so much younger, fitter and stronger. They, meanwhile, came to look on me as something of an oddity, especially as a linebacker.

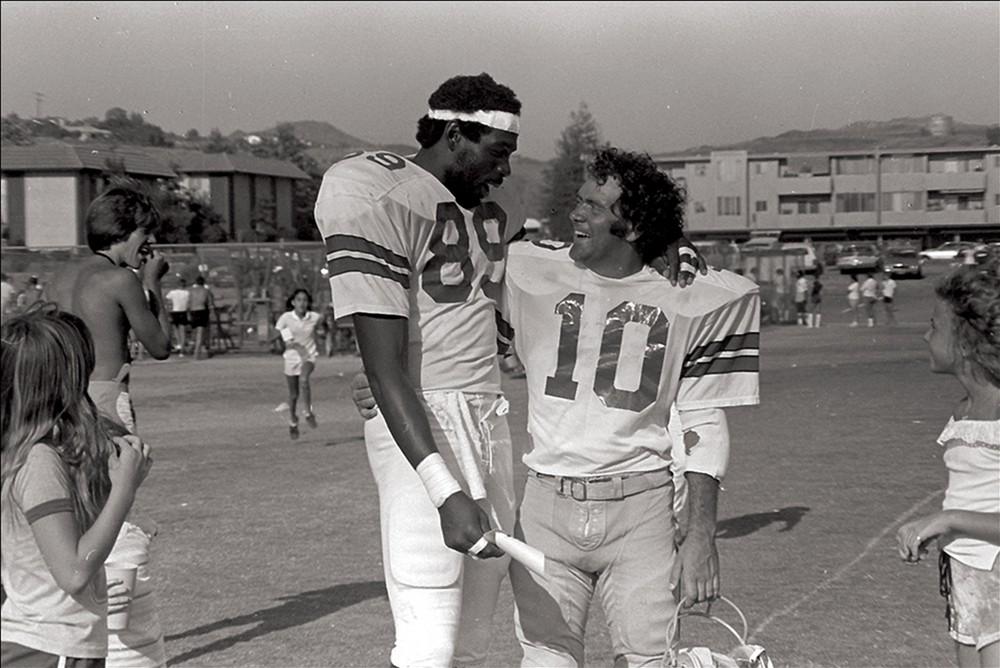

After the first week they had me lined up in a confrontation with Ed ‘Too Tall’ Jones, the biggest man I had ever seen, standing some six foot ten and built like a brick ‘public convenience’. He was a living legend in American football, and was part of the Dallas Cowboys’ famed and much feared ‘Doomsday Defence’.

Offside

The coach rubbed me down, and whispered the play call ‘on two’. This enabled me beforehand to know when to move. He would call some play like ‘Delta Green Shotgun 85, 25 – Hut! Hut!’

The second time he called ‘Hut’ would be the signal for me to strike (i.e. on two). This is done in a game in an attempt to lure the opposition offside.

The coach said to me, ‘Number Ten, I want you to walk all over him, hit him in the numbers, chew him up and spit him out!’

We went down into what American footballers call a three-point stance, a crouched position with one finger of one hand touching the ground, ready to spring forward. We were barely a yard apart. The other rookies looked on, whooping in delight and shouting encouragement.

‘Go get him, Max. Haul his ass!’

The coach whispered, ‘OK Number Ten, you ready?’

‘Yeah,’ I snarled, trying to look mean.

‘Delta Green Shotgun 85, 25 – Hut! Hut! . . .’

I leapt at ‘Too Tall’ screaming, totally committed and determined to knock him over. He stopped me with one piston-like hand, picked me up above his head like a child – and dropped me to the ground in a heap. I picked my crumpled body up with tears in my eyes. The coach could hardly stop himself from laughing.

‘What happened, Number Ten?’

‘I slipped,’ I said.

‘Number Ten,’ he went on. ‘You’re the waste of a good helmet! You’re too old, too slow and too small.’

‘Don’t mess about, coach,’ I replied. ‘Give it to me straight!’

‘You just ain’t gonna make it with us. You better try somewhere else.’

I slunk away, shouting back to him in a choked voice, ‘You wait till I paint a dragon on my helmet . . . !’

Max Boyce’s new book of selected poems, songs and stories including new unpublished material is the his first for almost thirty years is published on 1 November.

He will be signing copies at bookshops across Wales including Storyville in Pontypridd, Bookish in Crickhowell, Griffin Books in Penarth and Waterstones in Swansea and Carmarthen.

You can buy a signed copy of the book here. Max Boyce: Hymns & Arias – The Selected Poems, Songs and Stories (Hardback)

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

#89 in the photo is not Ed Too Tall Jones. That’s tight end Billy Joe Dupree. Also the top photo of Boyce is reversed.