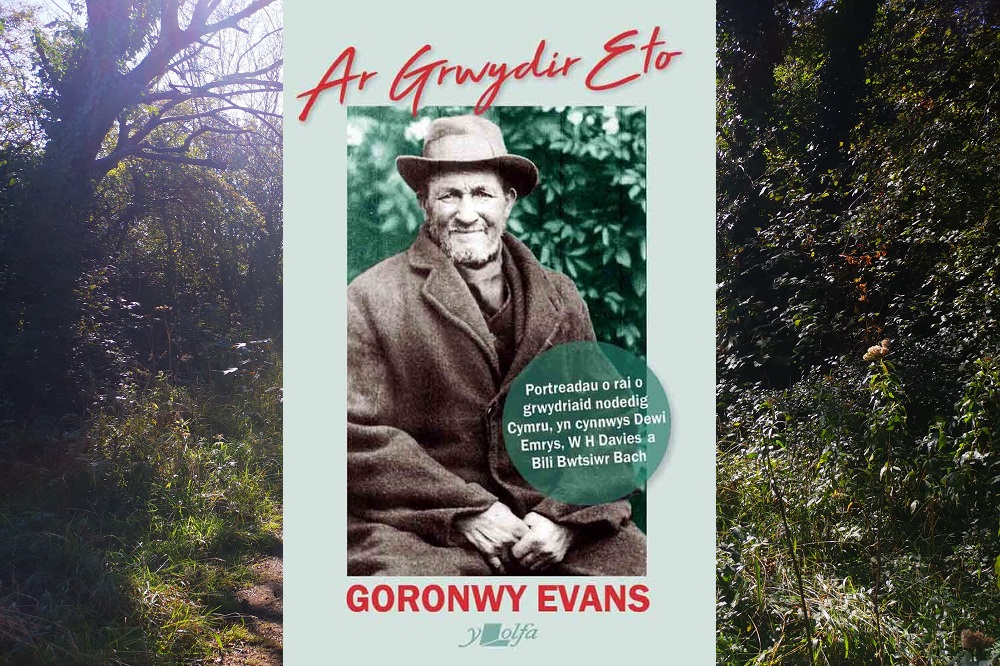

Review: Ar Grwydir Eto is a fascinating collection of tenderly-drawn vignettes, poem and essays about the tramps who used to travel the Welsh countryside

Jon Gower

The tramps who used to wander the Welsh countryside make for a fascinating subject as this collection of tenderly-drawn vignettes, poem and essays by the Lampeter bookseller and preacher Goronwy Evans amply proves. And, as you’d expect, the gentlemen of the road are a rum bunch, colourful characters each and every one.

There’s Dafydd Gwallt Hir, whose long hair, flowing as ringlets, was said to owe its sheen to washing it in milk in lieu of shampoo. A learned man and a bit of a Biblical scholar, Dafydd squirreled away a collection of his beloved books, hidden there and there in the Ceredigion countryside, as if he were a one-man mobile library. Then there was the many- times-chaired-bard, Dewi Emrys, who was at one time a preacher so powerful that they installed a phone in the pulpit in his Buckley chapel, so that miners working underground could listen in to his sermons. The experience of war affected Dewi Emrys deeply, as did the death of his father and he drifted into an existence of sleeping rough on London’s Embankment and in the crypt of St. Martin-in-the-Fields.

And most colourful of them all, perhaps, was John James, or John Waunfawr, who took a delight in mythical giants such as Gog and Magog, wore a kilt and carried a bow and arrow, the last of which did not stop him from befriending the birds and animals of his native patch, which he wandered on his tricycle.

Symbols

Such wanderers of road and by-way had their own codes, a hidden set of symbols they would carve or otherwise mark near a milk stand, or gatepost to let fellow travellers know if they should expect a welcome or have the dogs set on them. They would, in this way encode the profession of the person who lived there, especially if it was a policeman, as well as offer other useful info, such as whether there was a comfortable haystack to sleep in, or if there were fruit trees in the garden, or even suggesting that telling the occupants a sad story would reap rewards. At other times they would scatter bracken seeds in the chippings of a farm drive to tell fellow tramps to expect a welcome.

It is estimated that there were a million tramps in Britain after the Second World War, many of them former soldiers who were dispossessed or already lost in some way. They had their own codes of conduct, which often meant they ate outside, despite offers to do otherwise and they developed their own language, too. A ‘bull’ was a policeman; an old tramp was a ‘milestone inspector,’ tobacco was ‘hardup’ while ‘vacation’ was a synonym for prison. The little glossary of such terms is a real delight.

The book also discusses “tinkers,” a term the author of the little essay about them, Lyn Ebenezer defends against political correctness as his good friend, Finbar Furey, of the band ‘The Fureys’ is proud to wear the label. Tinkers have their own language, he tells us, a hybrid of Irish and English and indeed there are even three distinct dialects, being Cant, Shulta and Gammon.

Oral history

The book follows on from the success of a predecessor volume called Ar Grwydir and again draws on diaries, memories and oral history to record the passing of a peregrinating tribe who have now fled the land. I remember one of them who used to call once a year at our house in Pwll, Llanelli, always in September, always eating and drinking in the shadow of the hedge rather than at the kitchen table.

He always made us laugh as he regaled us with an account of the year that had gone by, a bit like the story told in Ar Grwydir Eto about the butcher’s son, Bili Bwtsiwr Bach who was rather too fond of his beer. One day he met the local preacher, Mr Rhydderch who cautioned him that he would never get to Heaven if he persisted in his ways. Bili answered with alacrity that he didn’t want to go to Heaven as there wouldn’t be anyone there from Llandysul to meet him. I’m sure even the good people of Llandysul will forgive the four-foot tall tramp who slept under rhododendron bushes in the summer, in a shed or storehouse all winter long for his judgment.

Bili, like all his fellow tramps added so much colour to rural communities, which in turn rewarded them with kindness, temporary work or at least a very welcome cuppa to ward off the cold.

Ar Grwydir Eto is published by Y Lolfa. You can buy a copy here…

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Diddorol iawn. Edrych mlaen i’w ddarllen.

This sound an amazing book. My grandfather who had been in WW1 apparently always gave the tramps money