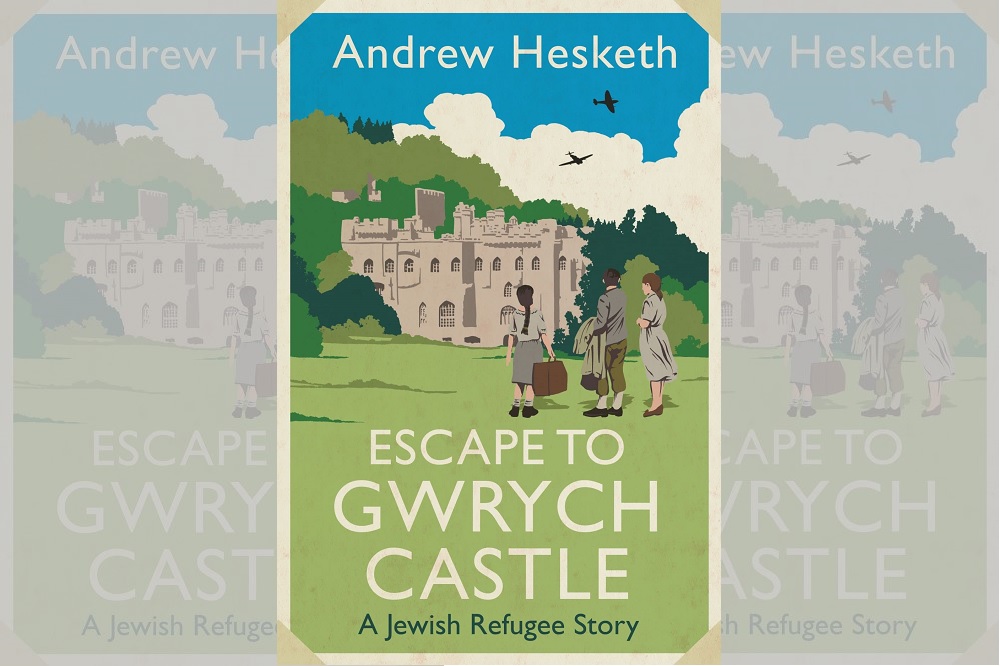

Review: Escape to Gwrych Castle – A Jewish Refugee Story by Andrew Hesketh

Jon Gower

A steely tale of resilience, displacement and community, this book tells the largely unknown story of the transformation of Gwrych castle near Abergele into a home for over two hundred Jewish refugee children during the Second World War.

They were some of those fortunate to be able to leave Europe as Nazi influence spread its dark cloud. But even that luck was tempered by the fact that they were travelling alone, separated from their parents, who would themselves be facing very uncertain futures as the Holocaust loomed.

The plan was to establish a Hachshara, a training centre which would equip the young people with skills which they later employ as they established a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

A castle with extensive grounds, surrounded by good agricultural land was a good prospect for creating a temporary home for the refugees, but in truth it was a damp and draughty pile, where water ran down some of the interior walls and the sanitation and kitchen facilities were utterly inadequate.

Faith

Much of the book describes how the leadership of the Hachshara coped with both the day-to-day running of the place and tried to ensure their charges received a basic education and also observed the Jewish faith and its holidays.

They also had to find ways to fill the children’s time, from instituting volleyball, football, chess and other games as well as look after their health and medical needs.

It also chronicles the ways in which the local community in Abergele accepted and supported the newcomers, with anything from clothes and cakes, readily supplied gifts for young people who had spent much, if not all of their lives `as members of a mercilessly persecuted minority.’

The Hachshara at Gwrych also benefitted from charitable support from members of the British Jewry such as Rebecca Sieff, daughter of Michael Marks of Marks and Spencer.

Through such help, coupled with the hard work of young people who gathered firewood, cleaned the castle and managed to keep everyone fed, clothed and shod.

The Great Dictator

Members of the Gwrych community were particularly welcomed by local farmers who were faced with the twin challenges of being required to increase production at a time when their sons and agricultural workers were being sent to war.

Children visited the town to window shop and occasionally see new films such as The Wizard of Oz and Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator.

All was going relatively well at Gwrych until the Nazi invasion of Denmark and Norway – when suspicions about fifth columnists began to spread and anti-Jewish antipathy was spread by local agitators including the editor of Y Llenor and a local councillor.

The appearance of German planes overhead which were attacked by British fighters or ditched their payloads along the north Wales coast, followed by the Luftwaffe’s devastating bombing of Liverpool, added to the growing tension.

Pogrom

On the British level, fears of a German invasion led to a hardening of attitudes and Churchill’s talk of mass internment for all ‘enemy aliens.’

Some of the refugees at Gwrych knew all about being rounded up; ‘sixteen year old Eli Freier of Breslau had spent some time in the Buchenwald concentration camp after Kristallnacht,’ which was the pogrom against the Jews in November 1938.

Some Gwrych refugees were sent to the Isle of Man, while others were sent as far away as Canada, facing incredible hardships on a long journey that also had the Atlantic dangers of German U-boats while others were transported to Australia.

The irony of all this was not lost on Jews such as Wolfgang Billig who said ‘Because I came with a Polish passport and had a different sticker on the back of my alien’s registration book I was classed as a friendly alien and not interned…In Germany we were hounded as Jews and as enemies of the state and when we thought we were free from fear, most were again treated like enemies.’

Disasters

It is little wonder, perhaps, that Rabbi Sperber at Gwrych made an adjustment, adopting a new prophet to be the guiding hand of the Hachshara, replacing the humble shepherd Amos with Job, ‘a man whose faith was tested to destruction by repeated disasters and who lost everything important to him.’

The internments and deportations not only reduced the number of people living in Gwrych but also accelerated the process of people leaving of their own volition, especially as they reached the age of eighteen.

Somewhere between a quarter and a half of the the noar – the generic term for those under that age – was lost from the castle’s population in a period of ten months. The decline of what had been the flagship centre was pretty swift once it had started.

Sanctuary

Andrew Hesketh, a deputy headmaster at Ysgol Aberconwy, has been exhaustive and meticulous in the research for this book, which both briskly presents individual lives and sketches the larger context of the times.

It presents and preserves a telling moment in Jewish history, a gathering of persecuted people in testing times, who made friends, found succour, sanctuary and sustenance in the company of others in a draughty Welsh castle before dispersing again, or, far more cruelly, being once again forced to do so.

Escape to Gwrych Castle: A Jewish Refugee Story by Andrew Hesketh is published by Calon. It is available from all good bookshops.

Read an extract here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.