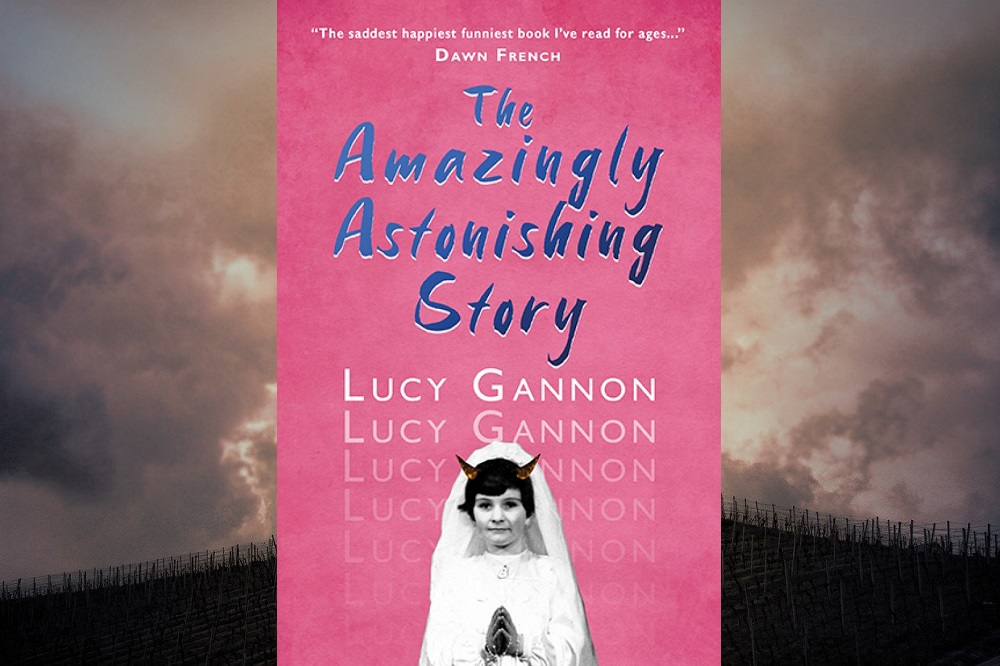

Review: The Amazingly Astonishing Story is an utterly engaging memoir of a working-class girl growing up in the fifties and sixties

Jon Gower

It’s not the easiest thing to turn misery into entertainment but in this candid and unflinching memoir Lucy Gannon does just that with aplomb and energy. It’s an account of growing up as the daughter of a father in the army, which involves no fewer than eleven moves, all of which contribute to a feeling of displacement and un-settlement.

There’s a period in a troubled ‘Bloody Ulster’ and ‘Bloody Omagh,’ where she encounters hatred all the worse for being casual, such as the man who comes up to her in hospital, where her mother is sick and asks if she is ‘the soldier’s bastard. Her childhood also includes a stint in a Cyprus contested by both Turks and Greeks and a spell in Egypt during the troubled time of President Nasser. It’s a tale of relentless trial and tribulation, even when the six year old Lucy is taken in by her relatives in Lancashire who get paid for doing so. Here she is seemingly molested by her Uncle Alf, whose creepy memory seeps through the pages of the book like an unwanted stain.

After her mother dies Lucy finds herself living with her dad and her step-mother. At first things work out decently well. That is until her new ‘mother’ has a baby, Anthony, who dies not long after being born. Lucy, deep in shared misery wishes she could herself die so that God could give the baby boy back to his mother. She attempts to end her life via hypothermia:

I know that if ever I could think the cold right up past my kidneys, as they float in a small sea of golden wee somewhere near my belly, and up past my heart, and all the tubes that run inside my neck, to my porridge brain, I’d have done it as last. In the morning there would only be an alabaster face on a white pillow and blue fingernails and a space where I used to be, right up to the empty sky. And then they’ll be sorry.

The principal redemption in this deft untangling of a writhing mess of childhood miseries is such fine use of language. It’s sometimes piercingly funny such as when Lucy finds out that Saint Ignatius of Loyola used a scourge to do penance, slicing into his flesh with relish. ‘At first I thought he must have rubbed it in, but then I realised it’s the other sort of relish. If he’d rubbed real relish he’d have gone lunatic with pain.’ Young Lucy, like Mrs Malaprop in Sheridan’s ‘The Rivals’ is adept at getting the right word wrong, so she tells us about ‘passionate leave,’ how unwanted clothes are collected to be sent to the ‘jungle’or mis-informs the reader that Limbo is like a ‘nursery, like Andy Pandy’s garden.’

Clear-eyed

The language is often heart-tearingly clear and clear-eyed, such as the description of Anthony, the dead little baby, with his ‘little white hands’ and ‘little wax nails’ to which Lucy reacts that it should be her ‘in the coffin and he should be in his little cot with the blanket…’ And then there’s Lucy’s writing in school where her English essays shine and anticipate her path in adult life towards writing award-winning TV drama.

As she begins to read more and more books she sometimes imagines herself as ‘a made up person in a book’ and suggests ‘there wouldn’t be much of me, always getting in the way and blocking the light. I would be written thinner…’ A crucial realisation comes when she sees that her made up stories are never as surprising as a book written by someone else.

One of Lucy’s survival mechanisms at home, school, in a convent and during a job in a sausage factory is inventing friends for herself. That sprightly, playful child’s imagination reminds one of Keith Waterhouse’s ‘Billy Liar’ and that young man’s dreams which allow him to deal with the drudge of working for an undertaker. Some of Lucy’s dreams are simple, just a horse with its head down, nibbling grass in a field but such sequences quickly sour and her dreams that can last all day make the world feel full of badness, sadness and madness.

But they do help her cope. She’ll let herself into the house and ‘slip up the stairs in Indian moccasin feet’ to meet her friend Cheyenne Bodie on the landing where she makes the ‘enemies below’ sign to him. Cliff Richard and Bobby McVee will casually join her at the table as she does her homework. Or she Lucy is a beautiful girl in the French resistance while air ace Douglas Bader is her dad. By the time she attends Confirmation Class she’s trying out new names for herself, such as Lucy Mary Theresa Frances Bernadette and imagining a married life for herself and a ‘lovely full-up house’ complete with nappies drying by the fire.

This utterly engaging memoir, which brings to mind other fine autobiographicals such as Kerri ní Dochartaigh’s ‘thin places’ and Lorna Sage’s ‘Bad Blood’ is interlaced with songs and song references so that it supplies its own soundtrack, a sort of childhood and teenage jukebox, full of Radio Luxembourg, the Everly Brothers and Elvis. But the biggest musical surprise comes in the form of Lucy’s chance encounter with the real-life Beatles and with John Lennon, who is beautiful, like a Greek God. But even that encounter pales into insignificance by comparison with the epiphany that happens pretty much at the end of the book. Gannon also signals that there’ll be more memoir to come. I for one, anticipate the next volume… with, well, relish.

The Amazingly Astonishing Story is on the shortlist in the creative non-fiction category for this year’s Wales Book of the Year. It is published by Seren and you can buy a copy here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.