Review: The Man in Black sheds light into very dark corners of the human psyche

Jon Gower

This is a very level-headed account of the arrest and trial of a north Wales cinema owner who killed four men and did so most callously and coldly. His defence lawyer Dylan Rhys Jones gives us an insight into the process of trying to defend a man who openly admitted the crime in an early police interview and whose souvenirs of the killings included the murder weapon itself.

When he later changes his story Moore tries to pin the blame on a friend called Jason, the same name as the psychopath in the Friday the 13th movie franchise: these would have been films showing in Moore’s little cinemas, which the avuncular owner wanted to be hubs for the local community.

This was the same man Alex Carlisle, QC described as “the man in black, with black thoughts and the blackest of deeds” when he opened for the prosecution in court and those black clothes, of course, went naturally with the job of film projectionist.

The book isn’t a portrait of a killer because that “would be impossible”. But it does show us the way in which the trial – or perhaps the very existence of Moore – had on his legal representative, such as lurid flashbacks of the gruesome images he’d amassed in his memory banks, especially when he visited the scenes of the crimes. One in particular– a remote spot set among the conifers of Clocaenog forest – is particularly unsettling, as the silhouette of the body can still be seen on the ground long after the cadaver itself has been removed.

The reality of the murders leave Jones feeling dirty and tainted and the unsettling experience of working on Moore’s behalf partially explains the breakdown, akin to PTSD, that Dylan Rhys Jones subsequently suffered:

“I had met bad people before, I had been surprised and sometimes shocked by what people had said and done, but this case was very different. The whole experience stirred emotions in me which made me question whether I was doing the right thing in representing this man. I was questioning whether I should be wishing him a Merry Christmas and exchanging idle pleasantries with him over a cup of tea. I was beginning to feel that I had encountered what some would call a force of evil.”

Unsettling

Indeed the experience of working on Moore’s behalf affects his solicitor so profoundly that on one occasion he believes that someone is coming at him with a knife, even though there isn’t anyone there.

There are still occasional moments when Dylan Rhys Jones feels sorry for him but these are swiftly counterbalanced by learning about Moore’s darkly kinky and perverse inclinations, as detectives discover a police uniform at his house, along with a truncheon and various Nazi memorabilia and the brutal violence of the crimes themselves is revealed.

I’ll spare you the grim details. But all the while, as the case proceeds through the courts and Moore is moved from Walton prison to become a category A prisoner in Wakefield nick, Moore remains inscrutable, out of range, not allowing any sense of the feelings, desires, experiences and appetites which drove him.

More unsettlingly, the book suggests that these are like the “hidden failings which we all possess as humans but choose never to display to others”. The weight of all this sort of realisation, coupled with those flashbacks, with mental anguish and failing health leads Dylan Rhys Jones to plan his own suicide, a plan only stymied by his complete and utter breakdown.

Arctic

There have been some excellent books about cold-hearted killers over the years, such as Gordon Burns’ Happy Like Murderers and Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song. This absorbing, honest and adjudgedly balanced book similarly sheds light into very dark corners of the human psyche and into a world of twisted and depraved desire.

It also gives insights into the procedures and processes of criminal justice – the rivulets of coffee in cramped interview rooms, the smell of sweat in the holding cells, the joshing in the wigging rooms for the learned barristers.

But it is a book with a very dark heart. In one interview Moore detailed some losses in the past year, when his mother died, followed by two of his dogs, then a cat and finally his koi carp in the pond. When asked if he is missing his mother his reply is chilling. “I miss her dreadfully… You see, killing someone was the only way for me to feel at peace.”

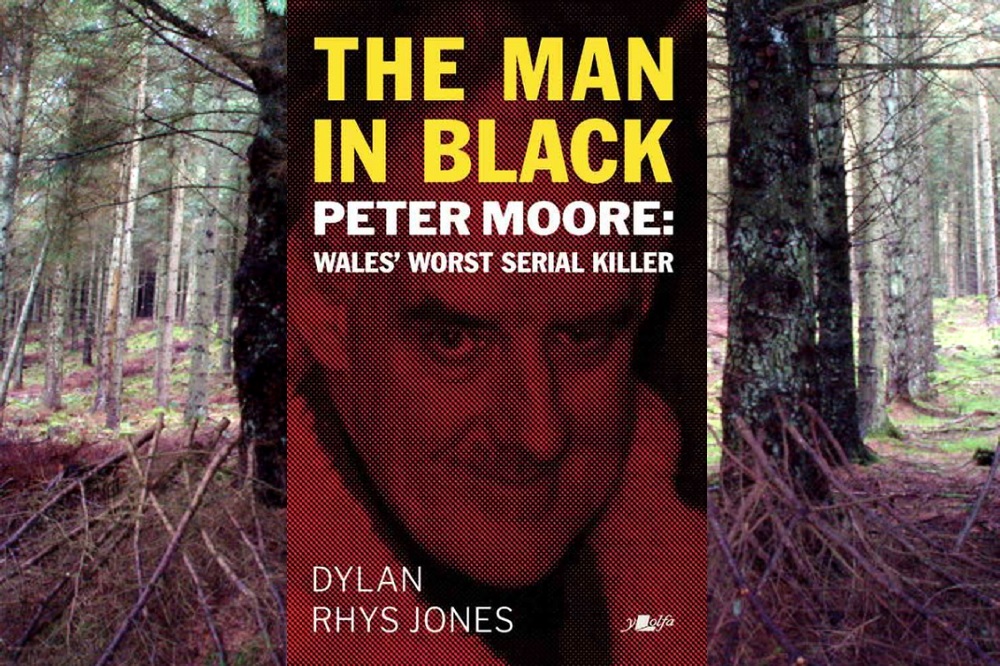

It is difficult to read this and not think of Norman Bates in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho and you may well find yourself flipping over the cover of the book so that you don’t have to see the gimlet eyes and thin-lipped grin of Moore staring out at you.

On one occasion the mild-mannered businessman, with an Arctic cold matter-of-factness, referred to one of the murders as a “job well done”. It is a brief but deeply unsettling example of his dispassion and disregard for fellow human beings.

For Peter Moore there may not be any peace, never any redemption, just as he displayed no remorse, but one sincerely hopes that in writing The Man in Black its author finds some sort of catharsis.

Dylan Rhys Jones has certainly written an honest, engaging and darkly lingering account of a man’s crimes and their consequences, and this a man now properly behind bars for the rest of his empty days.

The Man in Black is published by Y Lolfa and can be bought here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.