Valleys Witnesses: Miners Day details the real life of coal-mining communities in Wales in the 1940’s

In 1945, Penguin published Miners Day, about the contemporary experience of mining communities in South Wales. The author was the working miner B. L. Coombes and the book had a dozen illustrations by the artist Isabel Alexander, who spent extended periods recording people and places in the Rhondda.

A substantial new edition adds an introduction, notes and nearly the whole of Isabel Alexander’s visual archive. In extracts from his introduction, Peter Wakelin discusses the motives of the book’s creators and themes that still resound today.

Coombes and Alexander each had a passion to show the real life of coal-mining communities to a wide public, Coombes through words and Alexander through pictures. Coal mining was veiled more opaquely than almost any other sector from the view of educated people and metropolitan elites. For most of the country (at least until after nationalisation), the population on the coalfields was isolated in geography and distant in condition.

Many of its particularities, literally hidden below ground, were unimaginable to outsiders who had never contemplated what it might be like to spend the day in darkness, to labour in a space no higher than a dining chair, to bear the daily crush of fear that a husband or father might not come home from work, or to suffer injustices of wage cuts, industrial disease and injury. Yet this invisible sector was not an obscure irrelevance. It dominated large tracts of the country, directly employed 766,000 people in 1939 and fuelled every part of Britain and its Empire. In Wales, coal at its peak employed a quarter of the adult male population.

Against this divided and divisive culture Coombes and Alexander – Bert and Isabel – with other similarly engaged contemporaries believed the reality of mining communities had to be placed within the imaginative reach of far more people, and especially those in powerful positions. Atrocious working conditions and the scandalous deprivation and strife experienced by miners and their families had to be removed for good, but change would only come through understanding.

A subject that hangs like a black cloud over Bert’s text and Isabel’s images alike is ‘dust’. The word describes the coal waste that clogs water, land and air as well as the crippling disease that its inhalation causes. Pneumoconiosis, silicosis, ‘black lung’ or plainly ‘dust’ was more prevalent in South Wales than anywhere in Britain in the 1940s.

It had become an epidemic since the introduction of pneumatic drills and coal-cutting machines, bringing disability and death to multitudes of previously healthy miners. It is not yet fully understood but Bert notes that even a young man driving a haulage engine far from the coal cutters is suffering, he presumes from dust thrown up by the moving cable. Bert recounts the case of Jerry, who has had to give up work and in due course dies while those who should have helped him argue about whether ‘it was a weak chest or bronchitis, or an overload of coal dust or the scheming of a malingerer’. The unthinking vicar at the burial chants his customary ‘dust to dust’.

Dust

Dust despoils the whole environment. After going for an X-ray of his lungs in Neath Bert comes back on the bus through tracts of fields and rhododendrons, green and scarlet. He walks the last part towards Cwmgwrach: ‘A hundred yards along that road the taste of dust reminded me that the colliery screens were at work. My eyes were gritted and that acrid, bitter feel came to my palate […] It sort of holds your breathing and dries up your tongue’. The caption for one of Isabel’s drawings reads: coaldust in the air, on the curtains, on the kitchen table. To men and women with a passion for cleanliness, it means washing, cleaning, scrubbing; washing, cleaning … all over again.’ Her painting Washday presents a house hemmed in by tips, perhaps at Blaencwm or Cwmparc. The tips erode into a grey slurry that is filling up the intervening gulches.

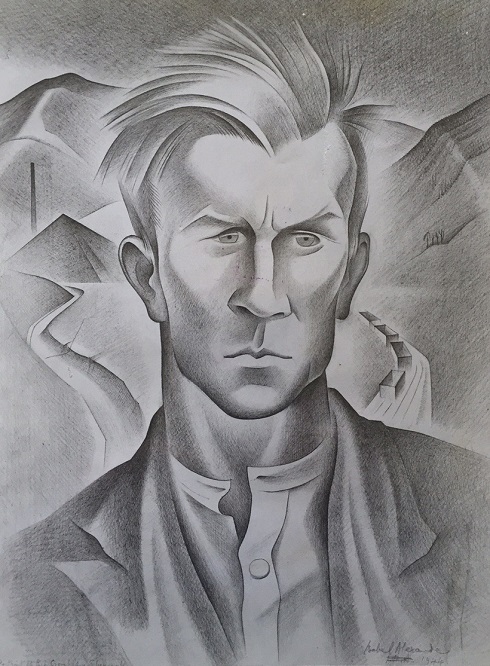

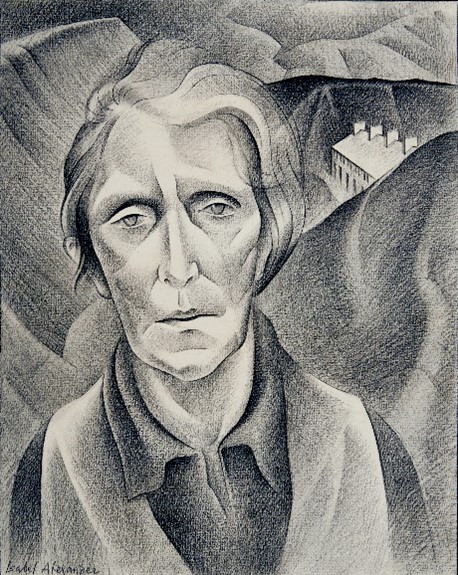

It is hard to think of any other painter or photographer who made so many portraits of coal-mining families in the period: the elderly, young miners, mothers and children, all treated as distinct individuals. Isabel was not trapped by the conventional portrayal of colliers black from the pit but looked instead at the men underneath the mask of dust, those who had retired through injury and the women who kept families alive in desperate times.

In the 1940s there was still little paid work in the coalfield available to women but they were fully occupied by the challenges of managing on low incomes, looking after children and fighting the battle against the black muck that crept into the house with ‘soap, scrubbing-brush and water, and then brown paper over the oilcloth so that it shall not be soiled’.

On the morning of Whit-Monday, a rare day of expected leisure: ‘Men, ordered out of the way by busy housewives, lounged along the streets and collected in groups on the points where the street-ends came out bluntly against the main road. All along that street and all the other streets the wives were on their knees scrubbing the lone flagstone which fronted their own hole in the wall’. Simultaneously, they were keeping fires alight, making a special dinner and taking part in celebrations.

Mothers in the coalfield were known to starve themselves so their children might eat well enough. The strain shows in Isabel’s portraits. The one published originally in Miners Day has the title ‘His wife has carried on her neverending battle’. Others show women at different points of their lives, different stages of despair. ‘The women wrap their shawls tight around their babies and shelter them with their love,’ Bert says, and Isabel shows the figure of a woman walking among pigeon lofts and washing poles with her shawl tied diagonally to hold a baby to her chest and, close-up, an emaciated young woman clutching her baby. An older woman, ‘Mrs G’ may be the finest of all Isabel’s lithographs: she is portrayed with deep humanity and recognition yet the wear of years of struggle shows in her face and her unfocussed eyes. A caption says she has brought up seven children, her husband is an ex-miner and her sons and grandson still work down the pit.

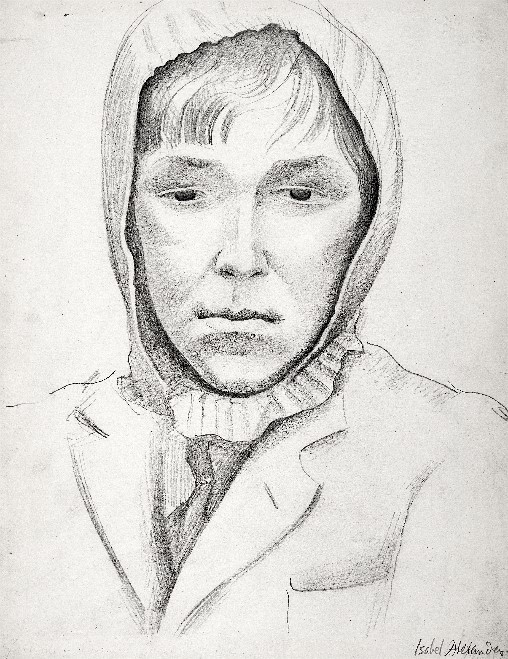

Perhaps the most remarkable strand of Isabel’s project was her study of children. Several pictures pick out distant gangs playing on the tips or scavenging coal to carry home but the series of portraits that she drew are an extraordinary rarity. A comparison could be made with the work of documentary photographers of the 1940s and 1950s in slum areas or with Joan Eardley’s post-war paintings of kids on the streets of Glasgow, but where their images were emotive and often shocking, Isabel captured her subject’s likenesses with interest in them as individuals. It showed how familiar she became to the communities she visited that she persuaded so many children to sit for her.

One series of sketches showed the actuality of hardship and poverty in the depths of January 1944 (probably some 700 feet above sea level at Blaencwm): legs bare to the elements, feet inadequately shod, one child with evidence of rickets. The war years were a period of relative prosperity and better diet thanks to war work and rationing, but the legacy of the hungry thirties persisted in the damage done to minds and bodies. Bert speaks of his hope that excellent new schools and children’s gifts for finding something good in dire circumstances will allow the coming generation to flourish.

Miner’s Day by B. L. Coombes / Rhondda images by Isabel Alexander, edited by Peter Wakelin, is published by Parthian in the Modern Wales series and is being launched at the Crickhowell festival on 16 October. You can order a copy here…

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Bert Coombes wrote a number of similar pieces, where did he come from and grow up?

Bert L Coombs was from Wolverhampton, grew up in Herefordshire, and moved to Resolven after WW1.

What an exquisite technique Isabel Alexander had, I went to view an exhibition in the library in Blaenau Ffestiniog a few years ago that captured the same feeling but for the life of me I cannot think of the artist’s name…

It’s time for a new wales 🏴 we in wales have got to stop being little Englanders and and be proud to be welsh start fighting for your children and grandchildren future in wales 🏴 kick all English party’s out of wales that’s the Tories Labour and all Brexit party’s it’s time for a new wales 🏴 the English government have robbed wales for years now it’s time for a new wales 🏴

Anyone interested in Welsh Mining. Take a look at Welsh Coal Mines Site. There is a Memorial page listing fatalities in the area, dating back to 18th century. It is being compiled by two ex miners. There are over 24,000 names so far. The 1960’s to 1990’s still being completed.