Wales’ Books of the Year, 2020 – what have our contributors been reading?

We asked some of our contributors to list their favourite titles of a year, when we all had more time to read than usual…

Wendy White

God’s Children by Mabli Roberts (Honno) is a fascinating novel based on the true story of Kate Marsden, the nurse and adventurer who attempted to find a cure for leprosy at the turn of the 20th century. The story begins with Marsden on her death bed, and hooks the reader from the very start with hints at her intrepid travels, her friendship with the Tsarina in Moscow and the defamation she suffered at the hands of the British press. With its inhospitable, icy backdrop and with controversy playing a large part in Marsden’s life story, this is an evocative and gripping read.

Geraint Lewis

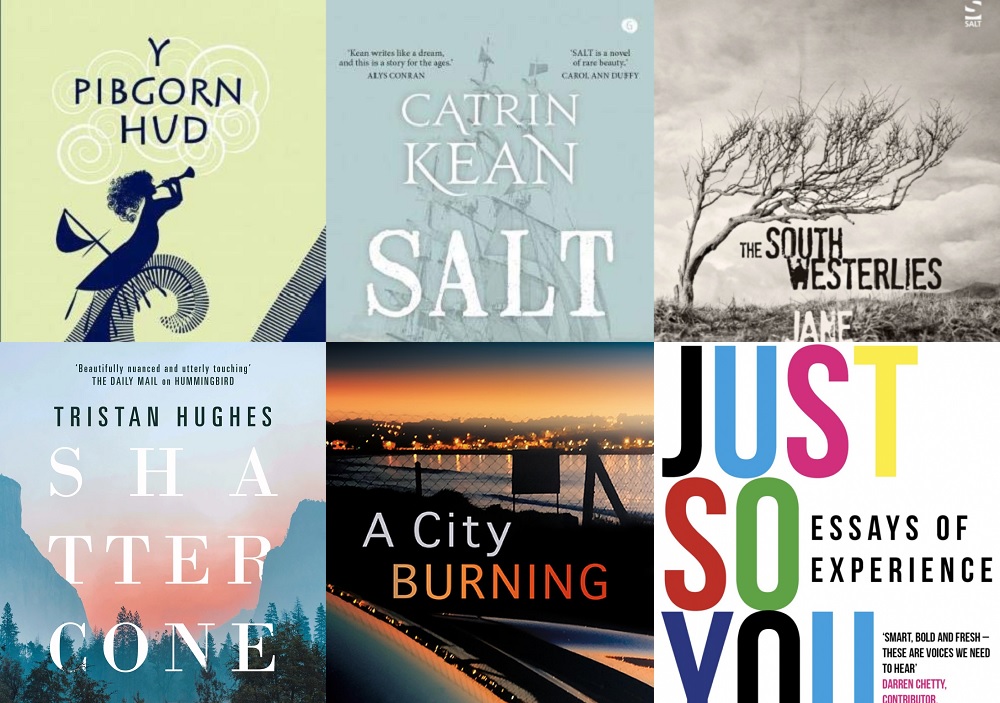

For the saddest of reasons I re-read two Welsh-language classics from the seventies this year, Siôn Eirian’s Bob Yn Y Ddinas (Gomer) and Dyddiadur Dyn Dwad (Gwasg Carreg Gwalch) by Dafydd Huws. Both books moved Welsh-language urban prose forward in significant though different ways. Both writers, who passed away this year, are sorely missed. I also enjoyed the delicate poignancy of Billy O’Callaghan’s My Coney Island Baby (Jonathan Cape.) The highlight of the year however was to be able to disappear for a few hours from 2020 to the Britain of 552 in the company of twelve-year-old Mina, the heroine of Gareth Evans’s enchanting Y Pibgorn Hud (Gwasg Carreg Gwalch.)

Rebecca John

It’s rare that a book makes me laugh aloud, but Miss Benson’s Beetle by Rachel Joyce (Doubleday) did many times over. It’s the story of middle-aged-before-her-time Margery Benson, who walks out of her teaching job and sets off on an expedition to find a rare golden beetle. She is accompanied by Enid Pretty, whose zest for life soon begins to change Margery’s view of the world. A touching, sensitive, and funny look at female friendship, adventure, and what it means to find yourself.

Richard Parfitt

The Summer of Reckoning by Marion Brunet, translated by Katherine Gregor (Bitter Lemon Press) subverts the picturesque version of Provence by describing the reality of working-class life in the Luberon. The boredom of a life with low expectations lived on the margins of society is evoked by telling the story of two sisters trapped in poverty and living with misogyny, casual violence and racism. After one of the sisters gets pregnant and refuses to reveal the name of her lover, her father sets out on a trail of vengeance that ends as a Tarantinian style dénouement leaving open ended any sense of justice or morality. This is the stuff nightmares are made of. If you like your coffee black and your eggs, fast, French and hard boiled, I can recommend.

Sarah Morgan

Welsh-born Sophie Mackintosh leads us into the normality of the cult inhabited by three sisters at the heart of The Water Cure (Hamish Hamilton). Their strange upbringing, painted as protection against the toxic world by their parents, leaves them truly vulnerable when three men arrive on their island shore. Taught to suppress any emotion and regarding men as a pathogen, Grace, Lia and Sky must work out how to fend for themselves, and each other, when their parents disappear. With each sister carrying the narrative in turn and in the present tense, this tale is at once oppressive and liberating.

Wendy White

The South Westerlies by Jane Fraser (Salt) is a truly enjoyable collection of short stories ‒ some with a touch of humour, some dark and some tragic, but all set within the glorious scenery of Gower. There’s the butcher building a boat for his hard-to-please wife in the spare bedroom above the shop, and a mother and daughter watching the solar eclipse from a clifftop where their relationship seems to be teetering on the edge too. Personalities and landscapes are skilfully portrayed and interwoven, and there’s a touch of local folklore and an air of mystery to many of the tales. An excellent, absorbing read.

Rebecca John

Based on the lives of the lives of the author’s great grandparents, Salt by Catrin Kean (Gomer) is a vivid, lyrical exploration of selfhood, home, and love. Beginning in the grimy streets of late-1800s Cardiff, it is the story of Ellen, who falls in love with Samuel, a ship’s cook from Barbados, and sets off with him to see the world. This is a short, exquisitely crafted novel, which made me smile and cry, and which will stay long in my mind.

Alan Bilton

White Walls: Collected Stories by Tatyana Tolstaya (New York Review Books Classics). That surname inescapably suggests a sense of Russian weight and heft, but Tolstaya’s work is wonderfully light on its feet, her work at once playful and witty, while also agreeably abrasive and irascible. Generally, her topic is bohemian folk all at sea amidst the grey managerial regime of the Soviet Union, finding refuge in art, booze, fantasy or nostalgia, as best they can. If you can imagine a Magic Realist Chekhov, you’re getting close, but her voice is all her own.

Wendy White

Wild Spinning Girls (Honno) is the third of Carol Lovekin’s novels and all have something of a Gothic feel. Each novel is set in a remote house and these rambling properties become characters in their own right. Tŷ’r Cwmwl in Wild Spinning Girls is no exception. Themes of grief and ancient magic are entwined to create an atmospheric, contemporary tale about two young women from very different backgrounds as they come to terms with parental loss. With the hint of a ghost at every turn of the page, Lovekin’s skilful unfolding of the story and poetic prose makes this a novel to savour.

Ant Heald

2020 has been the year of the lockdown binge, and my recommended read reflects this. Marilynne Robinson has mined, ground and polished four fragile and faulty interconnected characters to create the four flawless novels of her Gilead series. Somehow, the first three had passed me by, so the recent arrival of the latest, Jack (Virago) led me to gorge the whole sequence. All are set amid the strictured confines of mid-twentieth-century protestant mid-west America, yet each page glows with language that ramifies luminously with the universality of fine poetry, sloughing the tawdry surface of the ordinary to reveal a transcendent core.

Sarah Morgan

Responding to #justonebook to support Salt Publishing, I took potluck on three.

The Many by Wyl Menmuir is a bleak story of grief and claustrophobic obsession in an ethereal coastal town. Meanwhile The Lighthouse by Alison Moore is a tense and anxious tale of delusion as a diminished and rejected man leaves breakages in his wake when he repeats a childhood journey with the same lack of insight as his father before him. Finally, the beautiful collection of Gower stories, The South-Westerlies by Jane Fraser encapsulates the peninsula’s windswept essence, its beauty and sorrows, with carefully woven threads of time and place.

Richard Parfitt

I first heard about teenage runaway Tina Fontaine from an immersive BBC story called “Red River Women” that was then turned into Red River Girl: A Journey into the Dark Heart of Canada (Virago) by the same writer, Joanna Jolly. Over the last 30 years approximately 4,000 indigenous women and girls have been murdered or gone missing in Canada. Tina, failed by the very system set up to protect her, was raped, murdered and then found wrapped in a blanket weighed down with rocks and dumped in the river. True crime books often leave you questioning the reason why you’re reading them – but this is an important story that needs to be told as it deals with a genocidal crisis that is ongoing.

Sarah Morgan

Having adored Jessie Burton’s The Miniaturist for its curious artistry, and The Muse for its time shifting storytelling, I did not hesitate to dive into The Confession (Picador) when I discovered it on a Bookshop Day shopping spree. The tales of two women in search of themselves, separated by time but connected by aging yet powerful novelist Connie Holden, form a truly beautiful tapestry, full of mystery, reinvention, and discovery. Jessie Burton once more holds her characters and her readers in perfectly constructed worlds, and skimps on no detail, no turn, that will make the journey more exquisitely fascinating and complete.

Rebecca John

Caroline Hood has always been beholden to the men in her life. When her father opens a school with the intention of shaping the minds of young women, she welcomes the opportunity to teach and have her voice heard. Soon, however, a mystery illness begins to sweep through the small group of students, and Caroline must find a way to help them. Clare Beams’ novel The Illness Lesson (Transworld) defies easy categorisation: part realism, part haunting, part scream of feminist fury, and every page is a thing of intricate beauty.

Jon Gower

It’s been a bumper year for Welsh short stories with Tristan Hughes’ Shattercone (Parthian) providing me with equal measures of writer’s envy and reader’s delight with their superb evocations of wilderness and loneliness and people being stranded in both. Matthew G. Rees delivered another brightly imaginative and beautifully -crafted collection of tales in The Smoke House & Other Stories (Periodde Press) while Angela Graham’s debut collection A City Burning (Seren) announced a confident, stylish new voice in short fiction. Standout volume of the year? The sterling essays in Just So You Know (Parthian) are brilliant, wise and ever so timely. I have already re-read them for what they tell us about Welsh identity and belonging and much, much more.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.